CHAPTER ONE — THE MAYOR’S DAUGHTER

Claire learned early that a town could know you before you knew yourself.

Potter sat low and wide along the creek, buildings set back from the water as if they had learned something the hard way. The mayor’s house stood on the slight rise above Main, white-painted and practical, its porch squared and unadorned. It was not the finest house in town, but it was the one people pointed to when giving directions. Up there, they would say. That’s where the mayor lives.

Claire grew up inside that sentence.

She was the second child, the only daughter, and from the time she was old enough to walk unassisted, people remarked on her as if she were a feature of the house itself. Pretty like her mother. Tall like her father. Quiet, thank God. They pinched her cheeks, touched her hair, and asked questions she didn’t know how to answer yet. She learned to smile without committing to anything, learned to lower her eyes not from shame but from efficiency. It saved time.

Her mother kept order the way some women kept prayer—daily, exacting, without flourish. Dresses were pressed, shoes were lined beneath the bed, and nothing loud was allowed after supper. Her father worked late and spoke carefully when he returned, as if the house, too, were listening. At the table, he asked his sons about school and Claire about her manners. She answered correctly.

The town watched her grow the way it watched the creek after a hard rain—curious, invested, waiting for something to give.

By sixteen, she understood that people looked at her longer than they needed to. By eighteen, she understood why. She had her mother’s bone structure and her father’s height, which made her noticeable in a place where people preferred not to be. She wore her dresses modestly and learned which colors dulled attention, but it didn’t matter. Beauty, she discovered, was not something you possessed. It was something other people claimed.

The first summer she noticed Clyde was the summer the cicadas came on early and loud. He was older by a few years, home from somewhere not spoken about much, with hands already roughened by work that hadn’t happened in Potter. He stood too close when he talked, smiled like he was about to say something better than he did. When he laughed, it carried. When he left town for weeks at a time, people noticed the absence the way they noticed the weather.

They walked together in the evenings because there was nothing else to do. They talked because silence invited interpretation. He told her about places with names that didn’t mean anything to her yet. She told him about the creek’s moods, about which houses baked bread on which days, and about how her mother counted teaspoons of sugar into the jar every Sunday. It felt like an exchange. It felt like practice.

When she kissed him, it was because she wanted to know what would happen next.

What happened next, she learned, was that a town could take something small and repeat it until it hardened. By the end of the summer, people had decided who she was becoming. By fall, they had decided who she had already been.

She did not correct them. Correction required permission.

The war came and took men with it. Names left town faster than bodies returned. Some suitors died with honor, as people liked to say, and some died without witnesses. Clyde left in uniform and returned altered in ways no one discussed openly. He stayed long enough to be noticed and gone again before anyone could ask why. She watched him leave from the porch, her mother beside her, her father silent behind them both.

She did not cry. She had already learned how grief behaved in Potter. It did not like displays.

Marriage arrived the way most things did—through suggestion, repetition, and eventual agreement. Her husband was steady, kind in an orderly way, and employed in work that required attention but not imagination. He spoke to her as if she were something that needed care, which at the time felt close enough to love. When he proposed, it was in the parlor, with her parents present, his hat held respectfully against his chest. She said yes because saying no would have required an explanation she did not have.

They moved out of town within the year. Not far. Far enough.

Her mother helped her pack. The evening gowns were folded carefully, wrapped in tissue that had yellowed at the edges. Claire ran her fingers along the seams, remembering dances that ended before midnight, laughter that felt borrowed. She hesitated, then placed the box at the bottom of the trunk.

“We won’t need these,” her mother said gently.

Claire closed the lid anyway.

The years settled. Children came. Her body changed and returned to itself in ways that surprised her. Her hair lightened with time, the color shifting toward something softer, less sharp. She learned the rhythms of a different house, a different set of expectations. She was a good mother. She was told this often. She believed it.

Sometimes, when the children were asleep and the house was quiet enough to hear the clock, she thought about the version of herself that still existed in Potter’s memory. That girl did not age. She did not marry. She wandered.

Claire understood then that the town would always be ahead of her, holding a version of her she could not retrieve or correct. It would carry that girl forward long after she had put away the dresses and learned the weight of children sleeping against her shoulder.

She did not know yet how much the town would ask of her in return.

Outside, the creek kept moving, carrying what it could, remembering weight.

CHAPTER TWO — MEN WHO STAY

Jeremiah had always been there.

That was how people explained him, when they explained him at all. He worked the timber upriver, came into town on weekends for supplies, drank less than some and more than others. He nodded when spoken to. He remembered names unevenly. If he lingered, it was said to be habit. If he stared, distraction. No one thought of him as dangerous. Danger required motion, and Jeremiah rarely moved faster than he needed to.

Claire first noticed him when her youngest was still small enough to be carried on her hip. She had gone into town for flour and thread, the child warm against her side, his weight familiar. Jeremiah stood near the dry goods counter, hat in his hands, eyes following her in a way that was not bold enough to challenge and not subtle enough to ignore.

“Afternoon,” he said, a moment too late.

She nodded and kept moving. It was nothing. Men looked. Men always had.

The second time, he spoke longer. Asked after her husband. Asked if the children were well. His voice held no humor, no particular interest—only insistence, like someone reading from a list they did not understand but were determined to complete.

“They grow fast,” she said, because that was true of all children and required no further elaboration.

He smiled at that, though she had not intended it to be kind.

After that, she began to notice how often he appeared where she already was. At the creek bank in the evenings. Outside the church on Sundays. Standing just far enough away that she would feel foolish calling attention to it. He never touched her. He never raised his voice. He never did anything that required correction.

That, she learned, was the trouble.

Her husband noticed none of it. He worked long hours and slept deeply. When she mentioned Jeremiah once—only once—it was in passing, and he laughed.

“That fella?” he said. “Harmless.”

She did not argue. Argument suggested stakes.

The town folded Jeremiah into itself the way it folded in everything else that didn’t quite fit. He was given a place without being examined too closely. People made allowances. They always had. In a town where men left—to war, to land, to better chances—those who stayed were granted a certain patience. Staying counted for something.

Claire continued living. That was what saved her, for a time.

Her days were full of small, necessary acts. Washing, mending, listening. She knew the weight of her children in the dark, could tell which one had risen by the sound of footsteps alone. She took pride in order. In knowing where things belonged. In being reliable.

Her beauty did not leave her, though it softened. Time was kind in that way, or cruel depending on who was watching. Her hair lightened further, the color closer to wheat than gold now. She wore it pinned most days, loose only in the evenings, when it was just the family and the mirror.

Jeremiah noticed this, too.

He began leaving things. A bundle of kindling stacked near the shed. A trout cleaned and wrapped in paper on the back step. Once, a pair of gloves laid carefully on the fence rail. Each time, she removed them without comment, thanked him if he was present, and said nothing if he was not.

Refusal required clarity. Clarity invited response.

The town noticed the gifts and approved. Men providing for women had always been read as virtue. No one asked whether it was wanted. No one asked whether it was safe.

When Clyde’s name began to circulate again, it came quietly, carried by men who had returned from farther west than Potter liked to imagine. He had done well, they said. Land. Livestock. A kind of renown that came from having been early somewhere new. His return was spoken of as inevitable, though no one could say why.

Claire heard the name in the market and felt something old shift—not desire, not regret, but recognition. Some stories did not end. They only waited.

That night, she sat longer than usual after the children were asleep. The clock ticked. Her husband breathed evenly beside her. She thought of the boxed gowns she had never unpacked, of the girl the town still held in reserve.

Outside, somewhere beyond the edge of the yard, Jeremiah stood in the dark and watched the light in her window go out.

The town slept well.

CHAPTER THREE — THE NIGHT

The night Clyde returned, it did not announce itself.

There was no crowd, no whistle of arrival that carried through town. He came in the way men did when they did not want ceremony—dust on his coat, his name preceding him by hours at most. Someone saw him at the livery. Someone else swore they recognized the horse. By sundown, the story had found its shape.

Claire heard it last.

A woman at the market leaned closer than necessary and spoke the name like a test. Claire did not react. She paid for her sugar, thanked the clerk, and walked home with her basket balanced against her hip. The day remained intact. The sky did not change.

That evening, she bathed the children and brushed their hair. She listened to their small accounts of the day—what had been learned, what had been lost. She kissed them goodnight and stood in the doorway until their breathing slowed. Only then did she go to the trunk.

The gowns smelled faintly of tissue and time. She chose the blue one, the fabric still holding its shape despite the years. It fit more closely than she remembered. Her body had changed, but not enough to make it unfamiliar. She pinned her hair carefully, the way she used to, and stood a moment longer than necessary before the mirror.

She did not dress for Clyde. She dressed for the girl who had never been allowed to finish becoming herself.

She left a note on the table. Out for a walk. Back soon. It was true, as far as it went.

The air outside was cool, carrying the damp iron scent of the creek. The town lay quiet, its structures reduced to shadow and line. She walked without hurry, knowing the way by heart. Clyde waited near the edge of town, where the lantern light thinned and the ground gave way to softer earth.

He looked older. Not ruined, not improved—simply marked by time in a way that made him less certain of himself. They spoke briefly. There was no apology worth naming, no promise that required belief. He told her where he had been. She told him nothing he could carry away.

They did not touch.

When she turned back toward home, it was with relief as much as regret.

She did not hear Jeremiah at first. His footsteps were careful, placed with intention rather than speed. When she sensed him, it was as one sensed weather—pressure shifting, the air thickening.

He spoke her name as if it had been rehearsed.

She told him to go home.

He did not.

What followed did not unfold cleanly. There were words that failed to land, movements that misunderstood one another. The ground was uneven. A sound carried farther than it should have. Then there was only the creek, still talking, and the dark closing in around her.

The town woke to noise.

Jeremiah was caught near dawn, his hands red, his face slack with something that might have been shock or might have been relief. He did not resist. He did not explain. When asked where she was, he said nothing that could be understood.

They hanged him by midday.

People gathered because that was what people did. They told themselves it was justice. They told themselves it was enough. The rope did its work efficiently. When it was over, the body was cut down and carried away. The town exhaled.

Claire did not come home.

Her husband searched until his voice gave out. The children were kept inside. The mayor stood on the porch of his old house and said words meant to close something. The creek continued to move.

By evening, Potter had decided what it would remember.

The hanging would stand for the crime. The absence would stand for the woman. And the night, complicated and unfinished, would be allowed to settle into something simpler.

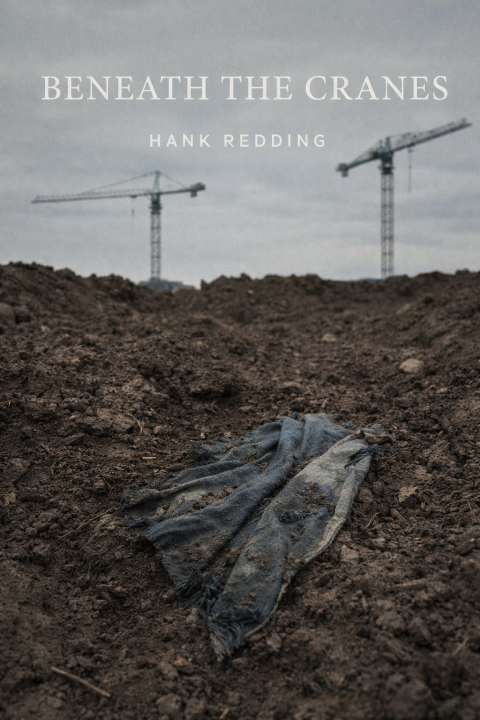

CHAPTER FOUR — BENEATH THE CRANES

The cranes came to Potter quietly, the way everything important did.

They rose first as outlines against the morning sky—thin metal arms stretching where trees once broke the horizon. The town spoke of progress in measured terms. New housing. Improved access. Jobs. Words that smoothed the act of digging into something reasonable.

The builder had been there six months when they found her.

He was not from Potter. That mattered. Outsiders noticed different things. He worked carefully, measured twice, kept his tools clean. The ground near the old creek had always been troublesome—soft in places, stubborn in others. When the backhoe struck something that wasn’t stone or root, the sound changed. He felt it through the seat before he heard it.

They stopped work.

What emerged first was fabric.

Blue, though the color had thinned with time. The weave held. Someone said it was odd for cloth to last like that. Someone else said nothing. When they uncovered bone, the air shifted. Conversation slowed. The builder stepped down into the pit himself, hands steady, as if this required witnessing.

She lay two feet down.

The dress was intact enough to tell what it had once been. Evening wear. Careful stitching. Buttons still holding. Her hair had not kept its color, but its length was unmistakable, arranged as if she had intended to be seen. She had dressed herself. That much was clear.

The sheriff—newer than the ground he stood on—called it in. They roped off the site. The cranes paused mid-reach, their shadows long and unnatural across the dirt. People gathered again. Some recognized the location. Some pretended not to.

They said her name out loud for the first time in years.

Claire.

The sound of it unsettled them. It belonged to someone younger, someone remembered incorrectly. The mayor’s daughter. The wandering girl. The absence that had been explained too many times to reopen.

Her husband was long dead. Her children were grown, scattered beyond Potter’s edges. One came back. She stood quietly while the remains were lifted, the dress handled with care it had not been given the first time.

No one apologized. There was no one left to hear it.

They reburied her properly, on higher ground. The preacher spoke about rest. The town listened politely. Then the cranes started again. Progress resumed. Foundations were poured.

The builder stayed late that evening, filling in the last of the disturbed earth. He worked slower than usual. When he was done, he stood a moment longer, looking at the place where she had waited for more than a century.

The ground looked ordinary again.

Potter carried on.

But beneath the new construction, beneath the clean lines and improved access, the soil remembered what it had held. Some things, once uncovered, did not settle back into silence.

Claire lay no longer forgotten—only late to be found.

And the town, for all its movement forward, had built itself at last on the truth.