I

The train had been slowing for some time before anyone remarked upon it.

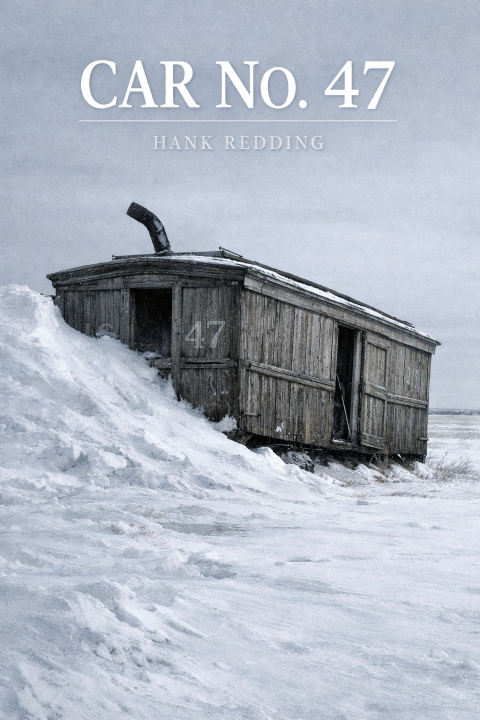

In Car No. 47 the change felt gradual, like breath easing from a chest. The iron wheels no longer struck the rails with their former insistence, and the stove pipe gave a thinner rattle against the roof. Most believed it was a siding — another pause in a journey measured now in days.

The immigrant car smelled of coal smoke, damp wool, and boiled cabbage. The stove sat bolted near the center, its iron sides chalked white from heat and touched by gloved hands more often than necessary. Benches lined the walls, thick oak planks worn smooth by years before this journey ever began.

Trunks were lashed against the rear boards with coarse rope to prevent shifting. Seed sacks rested beneath them. A crate of hand tools knocked softly against the floor each time the rails changed pitch.

The passengers had learned the rhythm of rail travel.

Slowings meant sidings.

Sidings meant waiting.

Waiting meant patience.

Thomas Whitcomb stood near the lantern bracket, pamphlet folded in his coat pocket. Earlier that evening he had read aloud again from the land circular — acreage available along the branch, soil dark and generous, wheat tall enough to shade a man’s boot. He had pronounced each word carefully, as though speaking it made it nearer.

Some had listened.

Some had slept through it.

Jakob Sørensen sat with his back to the wall, eyes closed not in sleep but in conservation. He had traveled before. He knew that warmth spent in worry could not be recovered.

Clara Meier kept her small trunk near her knee. Her fingers rested against the lid as if testing its temperature. Otto Krieger had untied and retied the strap on his own twice that evening, not because it needed securing but because his hands required occupation.

Marta Vollen shifted often, one hand resting beneath her coat against the small firmness of her belly. She breathed through her mouth to ease the smoke from her lungs. Each time the stove draft reversed, she lowered her head until the air cleared.

Ansel Bjornsen sat nearest the stove. He had not spoken since boarding at Fargo. Not once during loading. Not during Whitcomb’s reading. Not when Greta Nyland offered him bread. His silence had settled into the car as something ordinary.

Ingrid Halvorsen watched them all.

She kept her notebook beneath her seat, wrapped in cloth to keep the pages dry. She wrote most evenings, recording departure times, weather, names. It was not sentiment that drove her to it. It was habit. She had kept accounts before.

Outside, wind pressed snow against the boards hard enough to muffle what little sound remained.

Inside, boots stayed on. Blankets remained wrapped.

No one rose to look.

Thomas Whitcomb checked his watch by lantern light and cleared his throat.

“We’ll be moving again shortly.”

Repetition steadied him. A few nodded.

Ingrid did not look at Whitcomb.

She listened instead — not for wheels, but for the weight of them.

There was something different in the quiet.

She could not have said what.

II

Elias Kade shifted his stance.

He had been bracing against motion for so long that stillness felt like imbalance. When the train ran, even slowly, there was a constant strain through the frame — iron pulling iron, slack tightening and easing, boards speaking to one another in low complaint. He had learned to lean with it without knowing he had learned it.

Now there was nothing.

He placed one palm against the wall beside the stove.

He waited.

Nothing answered.

No faint tremor traveling through wood.

No distant pull through iron.

No subtle tightening of structure before forward motion resumed.

Only wind.

Time passed without being marked.

Whitcomb spoke once about drift ahead and clearing crews. No one replied. His words seemed to hang lower than the smoke before settling into the wool of coats and disappearing.

The stove pipe rattled again — not from movement, but from wind striking it at an angle. The sound was different. Hollow.

Sørensen opened one eye.

“Engine would strain against this,” he said quietly. “You would hear it.”

Whitcomb nodded as though that supported him. “Which is precisely why they’ve stopped us.”

Stopped us.

The phrase settled and did not move.

Ingrid adjusted the stove damper and watched the flame shift in response. The fire burned but did not draw cleanly. Without forward motion, the air seemed to hang inside the car rather than move through it.

She listened.

There is a difference between waiting and being left.

She did not yet name it.

________________________________________

The First Opening

Kade moved toward the door.

Whitcomb stepped forward.

“There is no need.”

Kade did not answer. He touched the latch with his gloved fingers and felt for vibration through the iron before lifting it. There was none.

“In this storm you will see nothing,” Whitcomb added.

Ingrid said, “Let him see.”

Not forceful.

Just clear.

The latch lifted.

Wind forced the door wider than intended.

Snow drove inward in a flat sheet and struck the boards with the sound of sand against tin. The air outside was not empty — it was crowded. Snow crossing itself in conflicting directions, wind folding over wind.

Kade stepped down carefully.

The drift reached mid-calf. The rail lay somewhere beneath it, invisible but present. He kept one hand against the side of the car as he moved.

The rear coupler was crusted in ice. He brushed at it. Cold iron met his glove.

He turned forward.

Where the next car should have been, there was only white.

No lantern glow.

No dark interruption in the storm.

He walked further than was sensible.

Ten paces.

Fifteen.

The car behind him dissolved into motion.

The storm erased distance.

It erased scale.

He could not tell whether the train was gone or merely swallowed by drift.

He stood long enough for cold to begin entering through seams in his coat.

He returned.

Inside, snow followed him in.

They watched his face more than they listened to his words.

“I cannot see the engine.”

Whitcomb answered immediately.

“That proves nothing.”

Perhaps it did not.

But it proved something to Kade.

________________________________________

The Waiting

Morning thinned slowly through the upper boards.

The car felt heavier in daylight.

No whistle came.

The stove burned unevenly. Ash accumulated in one corner of the grate where draft reversed.

Whitcomb checked his watch again though it had already stopped.

“They will know by now,” he said once. “They will count the cars at the next station.”

No one asked how far the next station lay.

Kade placed his palm against the wall again.

He closed his eyes this time.

He waited for the faintest tremor of iron traveling through wood.

Nothing came.

Ingrid wrote:

No whistle.

She did not add anything else.

________________________________________

The Decision

The rope lay coiled beside the tools near the rear wall.

It had been used to secure trunks during loading. It was coarse hemp, stiff from damp.

It was Dorn who suggested tying off.

“We follow the rail,” he said. “If they are there, we find them. If not, we return.”

Whitcomb hesitated longer this time.

Wind struck the boards in hard intervals.

“In this?” he asked.

“In this,” Dorn answered.

Kade did not argue. He tied the knot at the rear drawhead with hands that moved more confidently than a farmer’s should.

Ingrid noticed.

She said nothing.

The rope was looped around Dorn’s waist and knotted twice.

The door opened again.

Wind swallowed him almost immediately.

They held the rope between them.

At first, it tightened.

Then slackened.

Then drew forward in steady strain as Dorn walked.

They felt his weight shifting through it — cautious steps over buried rail, boot against drift.

The rope reached its length.

It held.

They waited.

Snow struck the boards.

No whistle.

No strain in iron.

After several long minutes, the rope jerked twice.

They pulled him back.

His face was raw and pale where wind had found skin.

“There are no tracks ahead of us,” he said.

Not anger.

Not fear.

Only report.

Snow had filled the rail beyond their wheels completely. If the engine had passed only yards before, the cut of its going would have shown — a corridor carved through drift.

There was none.

Car No. 47 stood alone.

III

The Journal

Ingrid Halvorsen removed the small leather notebook from beneath her seat.

She had wrapped it in cloth against damp. The edges had softened from handling, and a faint crease ran along the spine where it had once been bent too sharply and pressed flat again. It was not new. It had traveled before.

She did not open it immediately.

Around her, the others shifted in the narrow space between benches and stove. The rope lay coiled near the rear. Coal sacks leaned half-emptied beside the tool crate. Snow pressed against the boards in steady rhythm.

She opened the book.

The first pages bore earlier entries from before this journey — dates and small accounts from a life now folded behind her. She turned past those without pause.

The newer entries began at Fargo.

________________________________________

Three Days Out

Departed Fargo at dusk. Car loaded full. Stove lit before departure. Smoke heavy until draft settled.

Mr. Whitcomb read aloud from land circular. Wheat soil described as “dark and generous.” Says branch line newly graded beyond Jamestown. Freight runs twice weekly.

Ansel Bjornsen has not spoken since boarding. Eats when handed food. Watches fire.

Marta Vollen unwell but says child moves strong. Says she will not have it born on the train.

Wind rising west of the line. Snow began after midnight.

________________________________________

She paused there.

She remembered the sound of loading — crates striking plank, boots against ladder rung, Whitcomb calling names from the manifest as though calling them into future acreage.

She turned the page.

________________________________________

Second Day Out

Stopped twice for drift clearing. Delay of three hours near Valley City.

Otto Krieger concerned about seed sacks getting damp. Re-tied rope at rear.

Clara Meier keeps trunk near her knee. Says Bible belonged to her mother’s mother.

Jakob Sørensen says branch lines never cleared fully until spring.

Ansel still no speech.

________________________________________

She turned again.

The handwriting had grown smaller as space narrowed.

________________________________________

Night of the Storm

Train slowed near midnight. Mr. Whitcomb says siding while drift ahead cleared.

Wind strong against boards. Stove holding but draft uneven.

No whistle since stopping.

She hesitated.

She added the line from the present.

Mr. Dorn walked the rail.

No sign of engine.

Snow filled the track ahead.

________________________________________

She left space beneath the last line.

The page looked unfinished.

She did not close the book immediately.

Instead, she ran her thumb once along the edge of the paper as if testing its dryness.

Writing was not comfort.

It was order.

Around her, order had begun to thin.

She closed the notebook and placed it beside her knee.

IV

Coal

They brought the sacks forward into lantern light.

The canvas was stiff from damp where snow had crept beneath the door seam. Coal dust blackened the boards around the base of each bag. When Whitcomb first said three full sacks, Sørensen pressed his hand into the top layer and lifted it away coated.

“Two and some,” he said.

They measured by bucket.

The metal pail rang lightly each time it struck the sack rim. Ingrid counted under her breath without meaning to.

Two sacks and one third.

At their earlier rate of burn, perhaps four days.

Without motion — without clean draft — perhaps less.

No one said the number aloud twice.

They all held it once.

________________________________________

Food was counted beside it.

Dry bread gone stiff at the edges.

Salt pork wrapped in cloth.

Two jars of preserved cabbage.

A small sack of dried peas.

Flour intended for planting, not eating.

The flour was not mentioned.

Whitcomb suggested that if the storm cleared within two days, rations need not change.

Dorn said reduce them now.

Whitcomb called that premature.

Dorn called it arithmetic.

No one raised their voice.

The disagreement existed in breath alone.

“The children eat,” Ingrid said.

There were no objections.

She cut the bread into smaller portions than the night before. No one commented on the size. They ate more slowly.

Greta Nyland chewed longer than necessary, as if length of chewing could create more.

Otto Krieger folded his portion in half and placed part of it back into his coat. No one remarked on it.

Ansel accepted what he was handed and did not ask for more.

________________________________________

Coal burned faster without forward motion.

The draft reversed at intervals, pushing thin smoke back through the seams of the stove pipe and into the car. It stung eyes. Coats were lifted to cover mouths.

Sørensen adjusted the damper repeatedly.

“Air is wrong,” he said.

Without movement, the air inside settled instead of passing through. Heat rose to the ceiling and clung there. Cold pooled along the floor.

Boots felt colder by morning than they had the night before.

When Whitcomb checked his watch again, it had stopped.

He wound it once, shook it lightly, then returned it to his pocket.

“They will know by now,” he said. “They will count the cars at the next station.”

No one asked how far that station lay.

________________________________________

When the coal dropped below one full sack, they began feeding the stove smaller portions.

The fire burned less evenly. Ash built up along one side of the grate and forced flame toward the other. The iron sides of the stove glowed faintly at night, then cooled faster than expected.

Ingrid marked each reduction.

She did not write feelings.

She wrote numbers.

Whitcomb said they would be collected when the storm passed.

Sørensen said storms sometimes remained longer than men thought.

________________________________________

The final bucket from the first sack was emptied.

They heard it when the canvas fell flat.

The sound of emptiness is distinct.

Dorn looked toward the trunks.

Whitcomb followed his gaze.

Neither spoke.

________________________________________

Small Friction

That afternoon, Clara Meier reached for the jar of cabbage before Ingrid divided it.

It was not greed.

It was instinct.

Her hand stopped midway.

She looked at Ingrid.

Ingrid nodded once and opened the jar.

The contents were divided by spoon.

Clara accepted her portion last.

No one commented.

The tension dissolved without word.

But it had been there.

And now everyone knew it.

________________________________________

As the stove burned lower, cold began to alter small things.

Greta Nyland’s fingertips grew pale and then mottled.

Marta Vollen’s breathing grew shallower at night.

Otto Krieger began waking before dawn and sitting upright long before light thinned the boards.

Whitcomb spoke less frequently.

When he did, it was about procedures — how rail lines were inspected after storm, how manifests were verified. He spoke as if system would reassert itself by mention.

The stove burned low.

Coal dust clung to every seam of clothing.

They began to look at wood differently.

V

The Trunk

Cold gathered in the corners where benches met wall.

No one suggested the benches yet.

Not aloud.

Dorn stood and walked toward the rear where the luggage was lashed.

The trunks had been secured against shifting when the train ran. The rope that bound them was the same rope now lying near the door.

Snow had crept beneath the base of the stack and frozen in a thin crust along the boards.

“We begin with this,” Dorn said.

He did not touch it yet.

Whitcomb rose at once.

“That belongs to someone.”

“So does the coal,” Dorn replied.

The trunk he indicated was iron-bound and scarred along its edges. The leather straps were cracked but oiled. A name had once been painted across the lid, but only the faint outline of letters remained.

Otto Krieger stepped forward.

“That is mine.”

His voice held no challenge. Only acknowledgment.

He crouched beside it without being asked.

For a moment he rested both hands flat on the lid as if measuring its weight.

“What is inside?” Ingrid asked.

“Clothes. Papers. My wife’s things.”

There was no wife in the car.

No one asked where she was.

Silence held the question and let it pass.

Kade knelt opposite him and pressed his thumb against the seam where lid met base.

“Wood beneath the iron,” he said. “Dry still.”

Whitcomb shook his head. “If we dismantle luggage, what remains of order?”

Dorn answered him. “Warmth.”

No one contradicted him.

________________________________________

Otto Krieger unbuckled the straps slowly.

The metal clasp scraped against itself in the quiet.

He lifted the lid.

The interior smelled faintly of cedar and wool.

Inside lay folded clothing, stacked with care. A bundle of letters wrapped in cloth. A small framed photograph, the glass cracked at one corner. A pair of women’s gloves laid neatly atop the stack.

He removed the photograph first.

He did not show it.

He slipped it into his coat.

The letters followed.

He hesitated over the gloves longer than the others.

Then he placed them on the bench beside him.

“Take the rest,” he said.

No one moved.

It was Ingrid who stood.

She lifted each garment and shook it once before passing it along.

A heavy wool shirt went to Henrik Dahl, whose own sleeves had thinned at the elbows.

A shawl to Greta Nyland, who wrapped it twice around her shoulders without meeting anyone’s eye.

An extra pair of socks to Ansel.

The redistribution was quiet.

Practical.

Nothing remained in the trunk but wood.

Dorn took the hatchet.

The first strike rang louder than it should have.

The iron bands resisted at first. Then the wood beneath split along grain lines that had waited decades for this.

Each blow echoed in the confined space.

Whitcomb turned his back.

Clara Meier looked down at her own trunk.

The first plank was pried loose.

It fed the stove reluctantly.

Flame caught slowly, licking at the edges before taking hold.

Then stronger.

Heat rose.

People edged closer by instinct, not decision.

Otto Krieger did not weep.

He watched until the wood collapsed inward.

Ash settled into the grate.

No one thanked him.

No one apologized.

The warmth was answer enough.

________________________________________

The trunk wood burned through the night.

It bought them hours.

Nothing more.

By morning, the iron bands lay stacked beside the rear wall.

The stove ticked as it cooled.

They all looked differently at what remained in the car.

VI

Sørensen

Jakob Sørensen did not wake.

There was no moment of realization. No sudden intake of breath from those nearby. It was Clara who noticed first — the way his shoulders remained fixed beneath the blanket, the way the rise and fall that had been shallow for days did not resume.

She reached toward him and stopped short.

“Ingrid,” she said quietly.

Ingrid moved from the stove and knelt beside him.

His skin was cool where it had been warm the night before. Not frozen — not yet — but no longer holding heat of its own.

She pressed her fingers beneath his jaw, not to find a pulse but to confirm what the room already knew.

The stove ticked once.

No one spoke.

They did not ask whether he had struggled.

The cold had come by patience, not force.

They moved him carefully toward the rear wall, near the door where frost had already gathered in thin white veins along the boards. His boots remained on. No one suggested removing them. There would be time for such considerations later, if later came.

Ingrid closed his eyes.

She returned to her seat and opened the notebook.

She wrote his name plainly.

She did not write more.

________________________________________

For a time, they left him untouched.

The blanket remained wrapped around his shoulders and torso, thick wool folded twice over itself. Frost gathered at its outer edge where breath no longer warmed it.

The stove burned low.

Cold reached deeper into the car now that one source of shared warmth had ceased.

Dorn saw the blanket first.

Or perhaps he had seen it earlier and refused to see it.

He stood.

No one asked what he intended.

He knelt beside Sørensen and pressed his hand into the wool.

It was dry still.

“Blanket will burn longer than linen,” he said.

The words were not loud.

Whitcomb stood.

“There must be respect.”

“For the living,” Dorn answered.

Both statements hung between them.

Ingrid watched the blanket.

She did not look at Dorn.

She did not look at Whitcomb.

She looked at Sørensen’s boots, still dusted with coal and snow from days before.

“He warned us not to leave the car,” she said. “He understood the wind.”

No one contradicted that.

She stepped forward.

The wool resisted slightly when she lifted it from his shoulders — stiff where frost had begun forming along the outer fold.

She folded it once.

Then again.

The knife she used for bread cut through the center seam cleanly but not without effort. The sound of steel against woven fiber was sharper than anyone expected.

She handed half to Dorn.

The other half she replaced over Sørensen’s chest.

“He keeps his share.”

There was no ceremony in it.

Only measure.

Dorn fed the first half into the stove.

The wool smoldered before catching. The smell changed — thicker, heavier than trunk wood or linen. Smoke gathered low before draft found it.

Heat rose.

People leaned closer.

Sørensen remained where he had been placed.

His share intact.

Whitcomb did not speak again that night.

VII

Benches

They did not touch the benches that first night after the trunk burned.

They sat upon them as if they were still seats and not fuel. The oak beneath them held both weight and memory — thick planks worn smooth from years before this journey. Bolted through the floor into the frame, they had been meant to endure.

The stove burned low.

Cold collected along the boards near the door.

By morning, frost traced thin lines along the windward wall.

Dorn stood without announcement and rested his hand against the bench nearest the stove.

It did not move.

Kade crouched and ran his fingers along the bolts fastening it to the floor. Rust clung to the iron heads. He tested one with the tip of the hatchet.

It did not yield easily.

Whitcomb watched.

“If we remove too many,” Kade said quietly, “the wall will bow.”

Whitcomb laughed once — not in humor, but in disbelief that such concerns still held weight.

“You assume it will matter.”

No one answered him.

They began with the bench nearest the stove.

Dorn struck the first bolt with the back of the hatchet to loosen rust before attempting to turn it. The metal shrieked against iron when it shifted even a fraction.

The sound filled the car.

Greta Nyland covered her ears.

The second bolt took longer.

Kade braced the plank while Dorn worked the head loose, the hatchet slipping once against the iron and biting into wood instead.

When the final bolt gave way, the bench shifted unevenly, tilting toward the stove as though already leaning toward its end.

They pried it free in sections.

The oak was dense. The grain tight. Each split required force that cost them breath.

When the first section was fed into the stove, flame caught slowly, then with sudden strength.

Heat surged outward.

Faces flushed. Breath eased. For a moment, the car felt almost restored.

Ingrid did not move closer.

She counted.

One bench.

She wrote it down later without commentary.

________________________________________

By evening, the warmth had thinned.

The floor beneath the removed bench now lay exposed — bolts protruding where wood had once anchored them. Cold crept upward through the gap, subtle but constant.

The car felt narrower.

They sat closer by necessity.

The windward seam widened slightly, just enough for snow to filter in fine powder along the floorboards.

No one brushed it away immediately.

It melted beneath boots and refroze at night.

________________________________________

They removed the second bench the following day.

This time the bolts resisted less.

The frame groaned audibly when the plank was pried loose.

Snow pressed harder against the windward wall as if testing it.

The seam widened the width of a finger.

Clara Meier pressed cloth into it, but wind pushed through regardless.

When the second bench burned, the heat came quickly and left quickly.

Relief felt thinner.

Marta Vollen lay near the stove and did not wake the next morning.

Her blanket was divided as Sørensen’s had been.

The child was not written again.

________________________________________

The third bench required more effort.

Hands were weaker.

Dorn’s grip slipped twice.

Kade steadied the hatchet.

Ansel collected splinters as they fell, arranging them beside the stove in careful order.

The car shifted perceptibly when the plank came free.

A soft inward bend along the windward wall.

The structure no longer held evenly.

Cold entered without pause.

The fourth bench stood alone.

No one argued for keeping it.

No one argued for removing it.

It simply remained between them and flame.

That night, they dismantled it.

The bolts came free almost willingly.

The car gave a low, steady groan when the final plank was carried to the stove.

The floor beneath lay open to drift.

Cold entered immediately and did not wait for invitation.

The fire flared once more — bright, brief, hungry.

Ansel fed it carefully.

There was no wood left after that.

Only wall.

Only floor.

Only each other.

VIII

Final Entry

There was no more wood to consider.

The walls had been examined but not yet touched. Floorboards near the windward side had already loosened where bolts had been torn free. The car leaned perceptibly toward the drift — not enough to topple, but enough that balance required adjustment when standing.

Food ended that morning.

The final crumbs of bread were divided without comment.

The jar of cabbage had long been emptied.

Salt pork gone.

Dried peas counted, then not counted again.

Whitcomb coughed through the afternoon — short, dry expulsions that produced nothing. He no longer spoke of timetables or branch lines. He sat with his back to the wall and watched the stove.

Greta Nyland’s hands had gone pale beyond their knuckles. She held them near the iron without reacting when heat brushed skin.

Otto Krieger lay down and did not rise again that day, though whether from sleep or surrender no one asked.

Breath hung low and did not lift.

When they cracked the door for breath, light struck the interior with a brightness that hurt the eyes. The snow outside rose nearly to the roofline. The opening could not widen beyond a hand’s width without inviting collapse of drift.

Ansel tended the stove with pieces too small to matter.

He fed it as though habit alone could sustain it.

Ingrid watched him.

Then she reached for the notebook.

Her fingers did not bend easily.

The leather felt colder than it should have.

She opened to a fresh page.

The ink had grown lighter over the last two days. The nib dragged slightly against the paper where her grip weakened.

She began.

________________________________________

Eleventh Day

Fourth bench taken. No more wood but wall and floor. Greta fading. Mr. Whitcomb cough worse. Food ended this morning.

Wind quieter. Or we are.

Ansel steady. Fire too large. Smoke wrong. Door will not open more than hand width. Snow higher than roof edge maybe. I think.

We waited proper. We did not leave. Jakob was correct. Mr. Dorn says line must clear. I think line is there but not ours.

It is not the cold alone. Something presses. It feels like weight but there is no weight.

I hear —

The train is —

________________________________________

The pen hesitated.

A drop of ink pooled at the tip and spread into the grain of the paper.

Her hand moved again, but the line it drew was no longer word.

The nib slipped downward.

Ink thinned.

Then stopped.

________________________________________

She closed the book.

Or perhaps she did not.

The journal lay open beside her knee.

The stove burned through the last of the bench fragments Ansel had saved.

Oak collapsed inward. Iron ticked as it cooled and flared and cooled again.

Smoke gathered low before finding its way up through the bent pipe.

Snow pressed through the widened seam and spread in thin, steady lines across the boards.

No one rose to brush it away.

The rope by the door held its frozen curve.

The stove light dimmed.

No one spoke.

IX

Spring

The thaw came unevenly that year.

Snow did not vanish all at once. It settled inward, crust softening at the edges first, then collapsing under its own weight. Meltwater cut narrow channels through drift, exposing boards and rail in fragments before retreating again under night frost.

Sections of the northern branch line required inspection before regular traffic resumed west of the Dakota line. Frost heave had lifted rail in places. Couplings on idle cars needed clearing. Drift near shallow cuts had to be marked and removed before engines could pass safely.

Two men walked the line with iron bars over their shoulders and notebooks tucked inside their coats.

They moved without hurry.

Boots broke through crust where sun had thinned it. In shaded sections the snow held firm enough to support weight.

They nearly passed the drift.

Only the bent stove pipe, angled wrong against the horizon, marked that something lay beneath.

They stepped off the packed rail bed.

The snow along the windward side had collapsed slightly from melt. Beneath it, dark wood showed through.

They began clearing with bars first, then with hands where snow had softened.

The roof emerged.

Then upper boards.

Then the number.

47.

The paint had faded but held.

They cleared along the door seam until the lower drift loosened and fell inward in heavy sections.

The door resisted at first.

When it opened, snow slid across the threshold and into the car in thick sheets.

Cold air moved outward — stale, layered with ash and wool.

They stepped inside carefully.

The interior remained.

Rear wall leaning.

Floorboards pried free where benches had once been bolted.

The stove collapsed inward upon itself, iron warped and ash packed thick beneath the grate.

Blankets lay where they had been placed.

Boots remained near the rear wall.

Near the stove.

Along the boards removed for fuel.

The rope lay frozen in a curve beside the door.

They moved through the car methodically.

One pressed a hand against the windward seam and felt where boards had shifted under strain.

The other crouched near the rear coupling and brushed snow from iron.

The link remained.

The pin was missing.

Snow had filled the track forward completely. No corridor marked passage beyond.

At the front of the car, near where the final bench had stood, a small leather notebook lay half open against the floorboards.

Meltwater had fused several pages together.

One of the men lifted it.

He turned it once in his hands.

Opened it.

The pages separated in places and tore in others.

Ink had bled across the grain of the paper.

Names remained visible on the upper leaves.

The final page held a slanted line trailing downward.

He closed it.

Placed it inside his coat.

They stepped back outside.

One marked the location in his notebook.

The other measured rail alignment ahead of the car and made note of frost lift along the line.

The obstruction would be cleared.

They stepped back onto the track.

They did not look back.

Traffic would resume.

The line would hold.

Author’s Note

In the late nineteenth century, railroads operated branch lines across the northern plains to move freight and settlers westward. Many immigrants traveled in what were commonly called “colony” or “immigrant” cars — older freight cars fitted with wooden benches and heated by coal stoves. Conditions were spare. Travel was long. Delays were common.

Before automatic couplers became fully standardized, link-and-pin systems were still in use on certain lines. These couplers were vulnerable to failure, particularly in severe winter conditions.

Blizzards across the Dakota and Montana plains in the 1880s and 1890s routinely halted rail traffic for days. Snow could drift higher than the cars themselves. Telegraph lines failed. Trains were delayed. Records were kept.

Car No. 47 is a work of fiction. The weather, however, is not.