Chapter One — The First Note

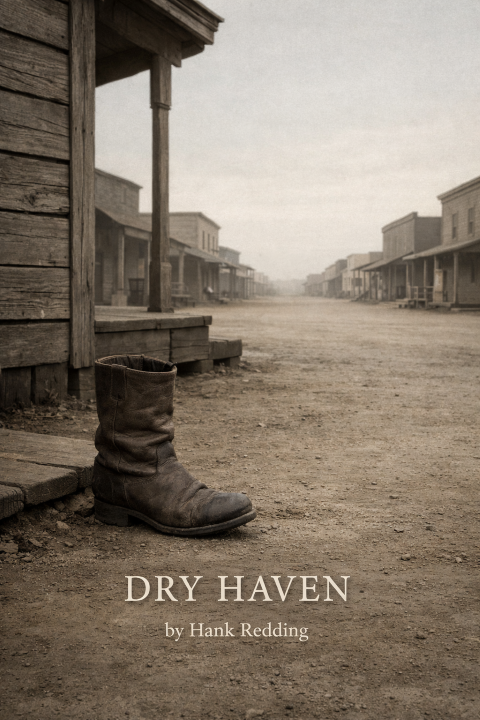

Dry Haven did not wake with sound. It woke with arrangement.

Light arrived first—thin, gray, unsure of its own authority—spilling over the clapboard fronts and the hard-packed street as if it had been sent to check whether the town still meant to be there. Smoke lifted from two chimneys, not because anyone was thriving, but because someone had learned the cost of not starting the stove early enough.

Sheriff Martin Wells rose before the town gave him a reason.

He sat at the small table in his kitchen with his coat still on, coffee cooling in a tin cup, and his notepad open to a page that already held yesterday’s weather and the names of two men who’d argued over a fence line like it mattered more than food. The pad was plain. The pencil was short. He had learned to trust what could be carried in one hand.

He wrote the date in the upper corner, then stopped. Dates invited later versions. They begged for comparison. He let the numbers stand anyway.

A dog barked once somewhere out in the direction of the livery and then went quiet, as if it had realized barking was wasted motion.

Martin folded the notepad closed and slid it into his coat pocket, flat against his chest, where it warmed slightly from his body. It was not for comfort. It was for access.

He stepped outside, pulled the door shut until it caught, and stood on the porch long enough to listen.

The street was empty in the way places were empty when people were awake inside them. No children. No men leaning on railings. No wagon teams lined up for something they didn’t yet understand. Just the faint scrape of a shovel somewhere behind a building, and the soft, steady whisper of wind brushing dried grass at the edge of town.

If you lived long enough in towns like this, you learned the difference between quiet and held.

Dry Haven felt held.

Martin walked toward the center of town without hurrying. His boots made the only consistent sound, and that suited him. Noise let people pretend they were busy. Silence made them honest, even when they didn’t mean to be.

He passed the church first—white paint gone chalky, cross still straight, door shut. A place that promised answers without offering proof.

He passed the grain buyer’s shed next—the big scale out front covered with a canvas tarp, corners tied down with twine. An older man would be there in an hour, measuring sacks and pretending the world could be stabilized with numbers.

A wagon sat near the well with its tongue resting on the ground. The horses were not hitched. The wagon was not being repaired. It was simply there, as if it had been set down and forgotten by a hand that had stopped needing it.

Martin had been in Dry Haven two years. Long enough that faces no longer turned at his approach just because he wore the star. Not long enough that anyone forgot he was still new. The town did not treat newcomers with cruelty. It treated them with patience, which could be worse.

When he reached the livery, Walter Finch was already outside, tightening a buckle on a bridle that didn’t need tightening.

Walter was not old, but he moved with the deliberate caution of a man who had learned what to avoid. His coat was buttoned high. His hands were thick, red at the knuckles. He kept his eyes down until Martin stepped close enough that looking away would become rude.

“Mornin’, Sheriff,” Walter said.

“Morning,” Martin replied. “You up early.”

Walter shrugged like it didn’t matter. “Horses don’t wait on daylight.”

Martin nodded once and let the silence do the next part.

Walter’s mouth tightened slightly, as if he’d been holding a word behind his teeth and was tired of it.

“He didn’t come down,” Walter said.

Martin didn’t ask who. He waited. Towns like this did not offer information without deciding how much weight it would carry.

Walter wiped his hands on his trousers and glanced toward the stable doors. The look wasn’t fear. It was correction—like a man pointing out a board that had shifted overnight.

“Samuel,” he said. “Samuel Kline.”

The name landed on Martin like a pebble thrown lightly. Not enough to hurt. Enough to mark a spot.

“He was due?” Martin asked.

“Paid for three nights,” Walter said. “Said he’d be gone on the morning freight. Wanted his horse ready before sun-up.”

Martin looked at the hitch rail. One horse stood tied there, head low, steam lifting from its nostrils in a thin ribbon. The animal wasn’t restless. That mattered. A nervous horse told stories a man wouldn’t.

“That him?” Martin asked.

Walter nodded. “That’s his.”

“And he isn’t?”

Walter’s gaze moved to the street behind Martin, then back again. An instinct. A habit. A way of checking whether this conversation was becoming public.

“No,” Walter said. “He isn’t.”

Martin waited one beat longer. Walter filled it.

“He rented a room at Nora’s,” Walter added. “Said he didn’t want to sleep in the loft. Paid her in coin, not scrip. Told her he’d be out before she started the stove.”

“Did he say where he was headed?” Martin asked.

Walter’s eyes narrowed slightly. Not at Martin. At the question.

“Said east,” Walter replied. “Said it like it wasn’t a place so much as a direction he owed somebody.”

Martin nodded. “When did you last see him?”

Walter didn’t answer immediately. He looked at the buckled bridle and adjusted it once more, not because it needed it, but because his hands needed something to do.

“Last night,” he said. “Just after supper. He came by. Checked his horse. Asked me if you were the kind that writes everything down.”

Martin felt the corner of his notepad press against his ribs where it sat in his pocket.

“And what’d you tell him?” Martin asked.

Walter’s mouth twitched. “I told him you were the kind that remembers what people forget they said.”

Martin didn’t smile. He had learned not to.

Walter cleared his throat. “He nodded like that was what he wanted.”

Martin looked at the horse again. There was dried mud on the lower legs, not fresh. Whoever owned it hadn’t ridden hard in the last day. The saddle on the rail inside the livery—Martin could see it through the open door—was still hanging. That did not match a man leaving before daylight.

Martin opened his coat and took the notepad out. He flipped it open with one hand and wrote without looking down long enough to appear uncertain.

Samuel Kline — expected to leave (east). Horse tied. Saddle still inside?

He underlined “expected” once, then stopped himself from doing it twice.

Walter watched the pencil more than the words. That was common. In places like this, writing carried the shape of authority even when it was only graphite on paper.

“You want me to go see Nora?” Martin asked.

Walter nodded quickly. “She’ll be up. She don’t sleep much.”

Martin closed the pad, slid it back into his pocket, and nodded once more at Walter.

“Keep that horse where it is,” Martin said.

Walter’s eyes met his. “You think he’s comin’ back?”

Martin looked at the street again. Still empty. Still held.

“I don’t know,” he said. “But I know I don’t want someone moving his things for him.”

Walter nodded like that was all the permission he needed to be worried.

Martin walked toward Nora Bell’s boardinghouse, the air sharpening as the sun climbed without warmth.

The boardinghouse sat on the edge of the main street, paint faded to the color of dust, steps worn smooth by boots that had climbed them tired and come down lighter. The sign out front was straight, but only because someone kept correcting it.

A woman’s hand, most likely.

Martin knocked once. The door opened almost immediately, as if she’d been waiting on the sound.

Nora Bell stood in the doorway with her sleeves rolled to her forearms and flour on her thumb. She was younger than most people expected to run a boardinghouse, older than most people expected to survive doing it alone. Her hair was pinned back tight. Her eyes were clear in a way that made men lie less, or lie better.

“Sheriff,” she said. No greeting. No apology for being awake.

“Nora,” Martin replied. “I hear Samuel Kline didn’t come down.”

Nora didn’t flinch at the name. That was the first thing Martin noticed. No surprise. No confusion. Just a small tightening at the jaw, like a door being pulled shut quietly.

“He didn’t,” she said.

“May I come in?” Martin asked.

She stepped aside.

The room smelled of boiled coffee and yesterday’s onions. A pot sat on the stove, not yet lit. That meant she’d been up long enough to prepare without committing to breakfast. The table was set for two, then corrected to one—one plate pushed slightly back, one cup turned upside down as if waiting for a hand that hadn’t arrived.

Martin didn’t point at it. He made a note in his head.

Nora leaned against the counter and crossed her arms. Not defensive. Just contained.

“Tell me what you know,” Martin said.

She nodded once, as if accepting the work.

“He came in before dark,” Nora said. “Took stew. Didn’t drink. Asked for hot water to wash his hands.”

“That’s not unusual,” Martin said.

“No,” Nora replied. “But he washed them like he was trying to get rid of something that wasn’t dirt.”

Martin held her gaze and waited. She continued.

“He asked about the east road,” she said. “How bad it was after the last rain. I told him it wasn’t the road you worry about so much as the wind.”

Martin nodded. “And then?”

Nora’s eyes drifted toward the staircase.

“He went up,” she said. “He didn’t come back down.”

Martin let that sit.

“Did you hear him move around?” he asked.

Nora’s mouth tightened. “I heard the floor once. Not walking. Not pacing. Just… a shift. Like someone sitting down hard on the bed.”

“What time?” Martin asked.

Nora hesitated.

Not long. Just enough to matter.

“After ten,” she said. “Maybe.”

Martin took the notepad out again and wrote it down.

Bell: heard room shift ‘after ten’ (uncertain). No further movement.

He capped the pencil with his thumb and asked, “Did anyone else come in last night?”

Nora shook her head. “Not after supper.”

“Did he have visitors earlier?” Martin asked.

Nora’s eyes didn’t move. “Not here.”

Martin let the wording stand where it was.

“Can I see the room?” he asked.

Nora’s hand moved slightly toward the stair rail, then stopped. Another small hesitation—permission weighed, not refused.

“You can,” she said. “But you should know…”

She didn’t finish.

Martin waited.

Nora exhaled through her nose, a quiet release.

“You’ll think it means something,” she said.

Martin kept his voice even. “It might.”

Nora’s eyes met his, steady.

“It won’t,” she said. “Not the way you want.”

Martin didn’t argue. He nodded once and climbed the stairs.

The hallway upstairs was narrow and smelled of old wood warmed too many times and cooled too fast. Nora followed two steps behind him, not close enough to hover, close enough to hear what he asked.

The room Samuel Kline had rented was the second door on the left. Nora opened it without ceremony.

It was a small room: bed, washstand, chair, a thin quilt folded tight at the foot like it had been trained to behave.

The window latch was still down.

No sign of forced entry. No broken glass. No scattered clothing.

That was what unsettled Martin most—how complete the room felt. As if absence had been cleaned up after.

Martin stepped in and stood still for a moment, letting his eyes take inventory.

The bed had been sat on. Not slept in. The blanket was wrinkled at the edge, not pulled back. The washbasin was dry. The towel was folded neatly, too neatly for a man leaving in a hurry.

On the chair sat Samuel’s coat—brown wool, worn at the elbows. Inside it, Martin could see the faint bulge of an inner pocket.

“He left his coat,” Martin said quietly.

Nora’s voice came from behind him. “He came in wearing it.”

Martin looked at her. “You’re sure?”

Nora didn’t blink. “Yes.”

Martin went to the chair and lifted the coat gently, as if it might carry heat that could be lost. He checked the pocket.

Empty.

He checked the other pocket.

Empty.

No wallet. No papers. No tobacco pouch.

No reason to leave a coat behind unless you intended to come back for it.

Martin set the coat down again, careful not to restore it too perfectly.

On the washstand sat a small tin cup. Coffee stain on the inside. A ring of it dried thin.

Martin leaned close. The cup wasn’t warm. It had been drunk hours ago.

He looked at the floor. No tracks in dust. The boards were too clean to offer much.

Then his eyes found the one thing that did not belong.

A single boot sat near the bed, toe angled slightly inward, as if it had been removed and set down without thought.

There should have been two.

Martin crouched and lifted the boot. The leather was stiff at the ankle, the sole worn but intact. A boot a man expected to keep using.

He turned it over. No mud clinging. No fresh grit.

He set it back down and wrote in his notepad without standing.

One boot left behind. Coat left behind. No bag. No papers.

Nora’s voice was quiet. “He wasn’t drunk.”

Martin didn’t look back. “Didn’t sound like he drank.”

“He didn’t,” Nora said. “He refused.”

Martin stood.

He looked at the window again. It was closed. The latch down. The sill held a thin line of dust undisturbed.

He turned slowly, scanning.

“Any other way out?” he asked.

Nora shook her head. “Just the stairs.”

Martin walked to the door and stepped into the hallway, then turned and looked down the stairs. Nora stood at the top step, hands on the rail, expression controlled.

“Who else has a key?” Martin asked.

Nora’s eyes narrowed slightly, not in anger—calculation.

“Nobody,” she said. “I don’t give keys out.”

Martin nodded. “Then you’re the only one who could’ve come in after he did.”

Nora didn’t flinch. “Yes.”

Martin watched her for a beat longer than politeness required. Her face held steady. If she was lying, she was doing it with practice.

If she was telling the truth, she’d had years of rehearsing restraint anyway.

“Walter Finch said Samuel asked about me,” Martin said.

Nora’s mouth tightened again. “That sounds like him.”

“You knew him before last night?” Martin asked.

Nora’s eyes moved away for the first time—just to the side, toward a wall that held nothing worth looking at.

“Everyone knows him,” she said.

Martin let the sentence hang. It wasn’t an answer. It was a boundary.

He took his notepad out again and wrote as he spoke, letting her see he was not collecting confessions, only shapes.

Bell: ‘Everyone knows him.’

He looked up. “That means he was here before.”

Nora’s gaze returned, steady. “It means he wasn’t a stranger.”

Martin nodded once.

He turned toward the stairs. Halfway down, he stopped.

“Nora,” he said.

“Yes?” she replied.

“When Walter said Samuel was ‘expected to leave’… who expected it?”

Nora didn’t answer right away.

From downstairs, Martin could hear the faint tick of the stove settling in the cold. The house making its small noises. The town keeping itself quiet.

Nora’s voice finally came, controlled and calm.

“He said it himself,” she answered. “That’s all.”

Martin held that in his mind and knew it wasn’t the whole truth.

He walked down the stairs, stepped back into the front room, and looked at the table again.

One place setting pushed back. A cup upside down.

Not grief. Not panic.

Preparation.

He wrote one final line before closing the notepad.

Dry Haven already speaks about him in past tense.

Outside, the wind moved through the street—soft, unhurried, like it had all day to work.

Martin Wells stepped onto the porch and looked toward the livery, where Samuel Kline’s horse still stood tied, waiting in the manner of animals that did not yet know they were being asked to keep a secret.

He did not rush.

He did not call for help.

He simply walked toward the next person who would correct him.

And he kept his notepad where it could feel his heartbeat through his coat.

Chapter Two — What Remains Consistent

Sheriff Martin Wells did not return to his office after leaving the boardinghouse.

He walked instead toward the grain shed, where the scale stood covered and the doors were not yet open. He had learned that offices encouraged conclusions. Towns, when approached sideways, preferred to offer conditions.

Henry Lask arrived while Wells was still standing across the street.

Lask moved with the certainty of someone who handled weight for a living. He did not rush, but he did not hesitate either. He unlocked the shed, rolled the tarp back from the scale, and set his hat on the nail inside the door before noticing Wells.

“Morning,” Lask said.

“Morning,” Wells replied.

Lask glanced at the street, then at the sky, then back at Wells. A survey. Not defensive.

“You here for business?” Lask asked.

“I’m here because Samuel Kline didn’t leave,” Wells said.

Lask nodded once. “That’s what I heard.”

Wells made a note of the phrasing without writing it down.

“What did you hear?” Wells asked.

“That he was meant to be gone by now,” Lask said. “That he paid his way and finished what he came for.”

“What did he come for?” Wells asked.

Lask lifted one shoulder slightly. “That wasn’t my concern.”

“What was?” Wells asked.

Lask rested a hand on the scale, steadying it though it wasn’t moving. “He brought grain in three days ago. Not much. Paid cash. Asked about storage.”

“And?” Wells prompted.

“I told him I don’t store for people who aren’t staying,” Lask said. “He said he wasn’t.”

Wells nodded. “Did he seem surprised?”

“No,” Lask replied. “He seemed decided.”

Wells took out the notepad.

Lask: Kline paid cash. Asked about storage. Said he wasn’t staying.

“You see him again?” Wells asked.

Lask shook his head. “No.”

“Anyone with him?” Wells asked.

Lask’s eyes narrowed slightly—not suspicion, calculation. “Not when I saw him.”

Wells let the distinction stand.

When Wells stepped away, Lask did not watch him go.

________________________________________

The schoolhouse was quiet but unlocked. Ada Corbin was already inside, chalk dust on her fingers, windows cracked to let the room air out before children arrived.

She did not startle when Wells appeared at the door.

“Sheriff,” she said. “You’re early.”

“Someone didn’t leave,” Wells said.

Ada nodded, as if the information had reached her before he had.

“Samuel Kline,” she said.

“Yes,” Wells replied. “You knew him?”

Ada considered. “I knew of him.”

“How?” Wells asked.

“He asked about enrollment,” she said. “For no one in particular.”

“That’s unusual,” Wells said.

Ada nodded. “Yes.”

“Did he say why?” Wells asked.

Ada wiped her hands on a cloth. “He said it was good to know what a place invested in.”

“And?” Wells asked.

“And I told him we teach the same children every year,” she said. “Even when their names change.”

Wells wrote.

Corbin: Kline asked about school. ‘Good to know what a place invests in.’

“Did he say he was staying?” Wells asked.

“No,” Ada replied. “He said he was passing through.”

“That matches what others said,” Wells said.

Ada met his gaze. “It would.”

Wells looked around the room. Desks were arranged neatly. No empty spaces. No signs of recent adjustment.

“Any absences today?” Wells asked.

Ada hesitated. Just long enough to confirm the question mattered.

“Yes,” she said. “One.”

“Who?” Wells asked.

Ada shook her head. “Not related.”

Wells didn’t challenge it. He wrote instead.

________________________________________

By the time Wells reached the church, Mrs. Eliza Rook was already unlocking the side door.

She did not ask why he was there.

“Morning, Sheriff,” she said.

“Morning,” Wells replied. “You open early.”

“Buildings don’t like to be surprised,” she said. “Neither do people.”

Wells stood with her while she worked the lock.

“Samuel Kline ever come in here?” Wells asked.

Mrs. Rook considered. “Not for services.”

“But?” Wells prompted.

“But he stood in the doorway once,” she said. “Long enough to count as entering.”

“What did he do?” Wells asked.

“He looked at the pews,” she said. “Then he left.”

Wells wrote.

Rook: Kline stood in church doorway. Did not sit.

“Did he speak to you?” Wells asked.

“No,” she said. “But he nodded. Like someone confirming something.”

Wells closed the notepad.

________________________________________

By midday, Wells had spoken to six people.

Every account aligned.

Every account stopped short.

No one contradicted another. They corrected instead—phrasing, emphasis, intention.

Samuel Kline had been present. He had paid his way. He had not intended to stay.

And yet, nothing explained why he had left behind:

• his coat

• one boot

• his horse

• his direction

Wells returned to his office only long enough to sit and review his notes.

He did not arrange them.

He read them in the order they had been written.

That was when he noticed it.

The same idea appeared in four different hands.

Not the same words.

The same assumption.

Samuel Kline had finished what he came to do.

Wells underlined nothing.

He turned the page.

Chapter Three — Corrections

Sheriff Martin Wells returned to the livery in the early afternoon.

He did not expect Walter Finch to be there. Finch had already finished the day’s work that could be finished without decisions. What remained would wait on people. Wells had learned that livery men often stayed close when horses belonged to someone who no longer did.

Finch was leaning against the rail, hat low, watching the street without appearing to.

“You come back often,” Finch said, not accusing.

“I do when I’m still writing,” Wells replied.

Finch nodded. “That figures.”

The horse was still tied. Its weight had shifted slightly, the rope slackened and retightened in a way that suggested patience rather than strain.

Wells stood beside it for a moment before speaking.

“You said Samuel checked his horse after supper,” Wells said. “Asked if I wrote things down.”

“I did,” Finch replied.

“And you said that was last night,” Wells said.

Finch’s eyes narrowed slightly—not defensive. Corrective.

“I said it was after supper,” Finch said. “Not last night.”

Wells looked at him. “You said ‘last night.’”

Finch shook his head. “I said ‘after supper.’ If you wrote ‘last night,’ that’s on you.”

The words landed carefully. Not hostile. Not apologetic.

Wells took out the notepad and looked.

The entry read:

Finch: saw Kline after supper. Last night.

Wells drew a line through last night and rewrote it smaller above the line.

After supper.

“Why does that matter?” Wells asked.

Finch considered. “Because supper doesn’t belong to the clock,” he said. “It belongs to the day.”

Wells closed the pad.

“Did you see him after that?” Wells asked.

Finch shook his head. “No.”

“Did anyone else?” Wells asked.

Finch’s gaze moved briefly toward the boardinghouse, then returned.

“Not here,” he said.

Wells nodded. He had learned to let the phrase stand.

________________________________________

Mrs. Lottie Ames lived two doors down from the church, in a house that had once been larger.

The yard was swept. Not clean. Swept. A distinction that mattered.

She answered the door herself.

“Sheriff,” she said. “You’re late.”

“I didn’t give you a time,” Wells replied.

Mrs. Ames smiled faintly. “You don’t have to.”

She let him in without asking why he was there.

The room smelled faintly of boiled starch and something floral that had been stored too long. A chair sat near the window. Mrs. Ames took it without ceremony.

“You’re asking about Samuel Kline,” she said.

“Yes,” Wells replied.

“I thought you would,” she said. “You’ve been writing.”

Wells did not deny it.

“What do you remember?” Wells asked.

Mrs. Ames folded her hands. “I remember he stood where he shouldn’t have.”

“Where was that?” Wells asked.

“At the edge of the well yard,” she said. “Right where people pass without stopping.”

“When was this?” Wells asked.

Mrs. Ames smiled again. “Before it mattered.”

Wells waited.

“He wasn’t looking at the well,” she continued. “He was looking at the space around it.”

“And?” Wells prompted.

“And he nodded,” she said. “Like someone agreeing with a thing he didn’t like.”

Wells wrote.

Ames: Kline at well yard. Before it mattered. Looked at space, not object.

“You said ‘before it mattered,’” Wells said.

“Yes,” she replied.

“When did it start mattering?” Wells asked.

Mrs. Ames’s hands tightened slightly, then relaxed.

“When people began speaking of him as finished,” she said.

“Finished how?” Wells asked.

She looked at him directly. “Finished being here.”

Wells closed the notepad.

“Did you see him leave?” Wells asked.

“No,” she said. “But I saw him stop.”

That was not an answer. It was also not nothing.

________________________________________

Wells crossed paths with Caleb Dunn near the rear of the grain shed.

Dunn had a plank propped against a wall and was shaving its edge down though no one had asked him to.

“You fixing something?” Wells asked.

Dunn shrugged. “Keeping it from getting worse.”

“What is?” Wells asked.

Dunn gestured vaguely. “Whatever’s next.”

Wells nodded. “You do work at the boardinghouse?”

“Sometimes,” Dunn said.

“Did you work there last night?” Wells asked.

Dunn shook his head. “No.”

“This morning?” Wells asked.

“Yes,” Dunn said.

“What did you fix?” Wells asked.

Dunn paused, blade resting on the wood.

“The stair rail,” he said. “It had shifted.”

Wells felt the answer settle.

“When did it shift?” Wells asked.

Dunn shrugged. “Hard to say. Wood moves.”

“Did you see anyone on the stairs?” Wells asked.

Dunn shook his head. “No.”

“Did you hear anything?” Wells asked.

Dunn hesitated.

Then: “I heard weight,” he said. “Not steps.”

Wells wrote.

Dunn: stair rail adjusted this morning. Heard ‘weight,’ not steps.

“When?” Wells asked.

Dunn looked at him. “After supper,” he said.

Wells looked up.

“That’s the second time someone’s corrected my sense of time today,” Wells said.

Dunn smiled faintly. “Then you’re listening.”

________________________________________

By late afternoon, Wells had corrected four entries in his notepad.

Not facts.

Framing.

Not what happened.

When it was allowed to matter.

Samuel Kline had not vanished.

He had been completed.

The town was not hiding that fact.

It was maintaining it.

Wells sat at his desk as the light thinned and read his notes again.

Every person had been consistent.

Every person had been careful.

And each had corrected him just enough to keep the story aligned.

Wells turned the page and wrote one sentence, then stopped.

He crossed it out before it could settle.

Instead, he wrote:

The town knows when a thing is finished.

He closed the notepad and set it face down.

Outside, Dry Haven continued as if nothing required correction.

And that, Wells knew now, was the first thing that truly mattered.

Chapter Four — The Question That Stayed Where It Was

Sheriff Martin Wells waited until evening to ask the question.

Not because he was unsure of it, but because he wanted to know how the town behaved when the day was finished making excuses for itself.

He found Deputy Frank Dillard outside the office, sitting on the step with his hat off and his boots unlaced. Dillard was young enough to still believe work ended when it was done, old enough to know better than to say so out loud.

“You heading out?” Wells asked.

“In a bit,” Dillard said. “Wanted to cool off first.”

Wells sat beside him without comment.

“Anyone come asking for Samuel Kline?” Wells asked.

Dillard shook his head. “No.”

“Anyone concerned he hasn’t left?” Wells asked.

Dillard hesitated. Just long enough.

“No,” he said again. “Not concerned.”

Wells nodded. “Why not?”

Dillard glanced at him, then away, toward the street. “Because people don’t usually worry about men who aren’t staying.”

“That’s an assumption,” Wells said.

Dillard shrugged. “It’s a practiced one.”

Wells let that settle.

“Has anyone told you what they think happened?” Wells asked.

“No,” Dillard said. “They tell me what didn’t.”

“And?” Wells asked.

“And that’s usually enough,” Dillard replied.

Wells stood.

“Lock up when you’re done,” he said.

Dillard nodded. “Yes, sir.”

________________________________________

Wells walked toward the edge of town where the well sat open to the evening air.

Mrs. Lottie Ames was there again, seated on the low wall as if she had always intended to be.

“You do that on purpose,” Wells said.

She smiled faintly. “I sit where questions pass through.”

Wells stood near her, close enough to be part of the space without interrupting it.

“I want to ask you something directly,” Wells said.

“That’s new,” she replied.

“I want to know,” Wells said, “whether Samuel Kline died in Dry Haven.”

Mrs. Ames did not answer.

She did not deflect.

She did not correct.

She did not soften the silence.

She simply remained where she was.

After a moment, Wells spoke again.

“Because if he did,” Wells continued, “then I need to know how.”

Mrs. Ames turned her head slightly and looked at him.

“You’re asking the wrong part of that,” she said.

“Which part is right?” Wells asked.

She considered. “Whether you need to know at all.”

“That’s not yours to decide,” Wells said.

She nodded. “It isn’t. But it has been decided.”

Wells felt the answer settle without landing.

“By whom?” he asked.

Mrs. Ames stood, smoothing her skirt.

“By the people who remain,” she said.

She walked away without another word.

________________________________________

Wells went next to the boardinghouse, not to ask questions, but to listen.

Nora Bell was closing the shutters.

“You going to ask me again?” she asked, without turning.

“No,” Wells said.

“Good,” she replied. “You already know what I’ll say.”

“What’s that?” Wells asked.

“That nothing happened in my house that didn’t already belong to it,” she said.

Wells waited.

“And?” he prompted.

“And if you want to find where something ended,” she said, “you’ll need to stop looking for where it broke.”

She closed the last shutter.

The door shut.

Wells stood alone.

________________________________________

Night arrived without ceremony.

Wells sat at his desk and opened the notepad again.

He reviewed the entries slowly.

Corrections.

Adjustments.

Clarifications that narrowed without answering.

He turned to a clean page and wrote the question he had been circling all day.

What did Samuel Kline finish?

He stared at it for a long time.

Then he closed the notepad without answering it.

Outside, Dry Haven settled into the night as if it had completed a task and required no further instruction.

Wells leaned back in his chair and understood something he had been resisting since morning.

The town was not protecting itself from the truth.

It was protecting the shape of what had happened.

And whatever Samuel Kline had done—or allowed—had fit that shape well enough to be absorbed.

Wells extinguished the lamp.

He did not write another word.

Chapter Five — What Was Already Repaired

Sheriff Martin Wells noticed the change because it was too clean.

He had walked the alley behind the boardinghouse twice already that day without reason to linger. It was a service path—trash barrels, stacked wood, a place where nothing important was meant to happen. That morning, one of the boards near the rear steps had been loose. Not dangerous. Just enough to announce itself when stepped on.

Now it didn’t.

Caleb Dunn was crouched near the stair rail with his tools laid out beside him, not working quickly, not working slow—just working until the thing stopped asking for attention.

“You finished?” Wells asked.

Dunn looked up. “Almost.”

Wells stepped closer and examined the board. The nails were new. Not bright. Just newer than the others.

“When did you fix this?” Wells asked.

“This morning,” Dunn said. “Like I told you.”

“Before or after I spoke to Nora?” Wells asked.

Dunn considered. “After.”

Wells nodded. “Why not wait?”

Dunn shrugged. “It didn’t need waiting.”

Wells let that stand.

“What made it loose?” Wells asked.

Dunn’s eyes flicked briefly to the stair above them, then back.

“Weight,” he said.

“Not steps?” Wells asked.

“Not steps,” Dunn replied.

Wells looked at the rail. The wood bore a faint scuff near the bottom, not deep enough to catch the eye unless you were looking for repetition.

“Anyone fall?” Wells asked.

“No,” Dunn said. “That would’ve left a mess.”

Wells wrote.

Dunn: board reinforced. Cause = weight. No fall.

“You’re certain,” Wells said.

Dunn nodded. “Certain enough to fix it.”

That was as close to certainty as the town allowed.

________________________________________

Wells walked toward the well yard again as evening approached.

The wagon he’d seen earlier was gone.

In its place, the ground had been smoothed. Not leveled—just corrected. A shovel leaned against the fence, its blade clean.

Mrs. Lottie Ames stood nearby, hands folded, watching nothing in particular.

“You moved the wagon,” Wells said.

“Yes,” she replied.

“Why?” Wells asked.

“It was in the way,” she said.

“Of what?” Wells asked.

Mrs. Ames smiled faintly. “Of walking.”

Wells stepped closer to the ground.

The soil was packed down evenly now. No ruts. No impressions.

“You filled this in,” Wells said.

“Yes,” she replied.

“When?” Wells asked.

“This afternoon,” she said. “Before it hardened wrong.”

“Hardened from what?” Wells asked.

Mrs. Ames looked at him. “From being remembered.”

Wells felt the answer settle without landing again.

“What was here?” Wells asked.

Mrs. Ames considered. “A pause.”

“That’s not a thing,” Wells said.

She nodded. “It becomes one if you leave it too long.”

Wells wrote nothing.

________________________________________

At the livery, the horse was gone.

Walter Finch stood near the rail, rope coiled in his hands.

“You moved him,” Wells said.

“Yes,” Finch replied.

“Where?” Wells asked.

“Out back,” Finch said. “Shade’s better.”

“Why now?” Wells asked.

Finch looked at him steadily. “Because he’d been waiting long enough to be noticed.”

“That’s not a reason,” Wells said.

Finch shook his head. “It’s the only one there is.”

Wells took out the notepad.

Horse relocated. No urgency cited.

“You didn’t ask me,” Wells said.

Finch nodded. “No.”

Wells waited.

“You would’ve said no,” Finch added. “Or you would’ve said nothing. Either way, the horse doesn’t deserve that.”

Wells closed the pad.

“Did Samuel tell you to move him?” Wells asked.

Finch shook his head. “Samuel told me he wasn’t staying.”

________________________________________

Wells returned to the boardinghouse as the light failed.

The stair rail was solid. The board no longer spoke when stepped on.

Inside, Nora Bell was washing dishes.

“You fixed the stairs,” Wells said.

“Yes,” she replied.

“You asked for it?” Wells asked.

“No,” she said. “Caleb noticed.”

“Did you tell him when?” Wells asked.

Nora set a plate in the rack and dried her hands.

“I told him after supper,” she said.

Wells looked at her. “After which supper?”

Nora met his gaze.

“The one that mattered,” she said.

Wells felt the correction complete itself.

“Did you clean the room?” Wells asked.

“No,” she said.

“But it’s been corrected,” Wells said.

Nora nodded. “Only the parts that would’ve asked questions.”

Wells took out the notepad and wrote his last entry of the day.

Adjustments made without instruction. All consistent.

He closed the pad and did not put it away.

________________________________________

That night, Wells lay awake longer than he meant to.

He understood now that whatever had happened to Samuel Kline had not required secrecy.

It had required alignment.

The town had adjusted wood, earth, and animals to match a conclusion reached without speaking.

There would be no moment to interrupt.

No act to isolate.

No single hand to hold responsible.

Only repairs.

Wells turned onto his side and stared at the wall.

He knew now that the longer he stayed, the fewer things there would be left to see.

And that, more than the silence, frightened him.

Chapter Six — What Was Left Alone

Sheriff Martin Wells noticed the thing that hadn’t been repaired because it was still asking to be noticed.

It was the boot.

He had left it where it was in the upstairs room—not as evidence, not as a marker, but because moving it would have meant deciding what it belonged to. By the time he climbed the stairs again the following morning, he had half-expected it to be gone, or set straight, or paired with its missing half as if it had merely been waiting.

It was none of those.

The boot sat exactly where he had left it, toe turned inward, leather dull and patient. The dust around it was undisturbed.

Wells stood in the doorway and did not enter.

Nora Bell was downstairs, moving quietly. He could hear the soft clink of plates, the controlled economy of someone preparing a room that would be used without being occupied.

“You didn’t fix this,” Wells said, his voice carrying down the stairwell.

“No,” Nora replied.

“Why not?” Wells asked.

She paused before answering.

“Because it wasn’t broken,” she said.

Wells stepped inside the room and closed the door partway behind him. The latch did not catch. It remained where it was, undecided.

He crouched and examined the boot again. No new marks. No sign that anyone had tested its weight or turned it to see whether it told a story if handled differently.

Someone had chosen not to touch it.

That mattered.

Wells took out the notepad and opened it to a fresh page.

He did not write immediately.

Instead, he listened.

The house sounded the same as it had the day before. Wood settling. A faint draft through the window frame. No sound that suggested interruption or urgency.

Finally, he wrote:

One object remains unchanged.

He underlined nothing.

________________________________________

Outside, the street had resumed its usual rhythm.

Wells walked toward the edge of town where the road bent eastward—not sharply, not decisively. The kind of bend that allowed people to tell themselves they were still going straight.

Jonah Pierce’s wagon stood near the freight shed, hitched and ready but not moving. Pierce himself was tightening a strap that was already secure.

“You’re not leaving,” Wells said.

Pierce glanced up, surprised only that the observation had been spoken.

“Not yet,” he said.

“You usually don’t wait,” Wells said.

Pierce shrugged. “Sometimes you do.”

“Why now?” Wells asked.

Pierce’s eyes flicked toward the road, then back. “Because something already left,” he said. “And it didn’t take its turn properly.”

Wells nodded.

“Did Samuel Kline ask you for passage?” Wells asked.

“Yes,” Pierce replied.

“When?” Wells asked.

“Before it mattered,” Pierce said, then frowned slightly. “That seems to be going around.”

“It is,” Wells said.

“Then you should know,” Pierce added, “I told him no.”

“Why?” Wells asked.

Pierce leaned against the wagon wheel. “Because he didn’t want to go east. He wanted to be done.”

“That’s not the same thing,” Wells said.

Pierce smiled faintly. “It is if you know where east ends.”

Wells wrote nothing.

________________________________________

By midmorning, Wells had walked every public space in Dry Haven.

Nothing new presented itself.

Nothing asked to be repaired.

Instead, he noticed something else: people adjusted around him.

Conversations paused until he passed. Tools were set down when he approached, then picked up again with the same rhythm. Doors were closed a moment sooner than necessary.

Not fear.

Consideration.

The town was making room for him the way it made room for weather—by altering small behaviors that left no record.

Wells returned to his office and sat at the desk without opening the notepad.

He considered, for the first time, what would happen if he left.

Not if the case ended.

Not if answers came.

If he simply stopped being present.

The town would not unravel.

It would correct itself.

That was when he understood the role he was playing.

He was not here to discover what happened to Samuel Kline.

He was here to decide whether it would ever be necessary to say it out loud.

Wells opened the notepad again.

He turned back to the first page.

The name still sat there, alone.

Samuel Kline.

No date.

No conclusion.

Wells closed the pad and placed it in the desk drawer.

He did not lock it.

Outside, Dry Haven moved carefully past his window, adjusting its pace to account for him.

And Wells realized that the longer he stayed, the more the town would learn how to finish him, too.

Chapter Seven — A Way to Finish It

The offer came without ceremony.

Sheriff Martin Wells found it waiting on his desk when he returned from lunch—a single sheet of paper folded once, placed squarely at the center as if alignment alone granted legitimacy. No name on it. No seal. Just ink, neat and economical.

He did not touch it immediately.

Outside, the afternoon passed at its usual pace. A wagon crossed the street. A door opened and closed. Dry Haven did not pause for his attention.

Wells sat and unfolded the paper.

It was a statement.

Not sworn.

Not addressed.

Just written.

Samuel Kline departed Dry Haven of his own accord during the night.

No disturbance occurred.

No property was damaged.

No assistance was requested.

Wells read it twice.

It was accurate enough to be believed.

Incomplete enough to endure.

He set it down and waited.

It did not take long.

Deputy Frank Dillard appeared in the doorway, hat in hand, posture careful.

“I didn’t write it,” Dillard said.

“I didn’t think you did,” Wells replied.

“They said you might want it,” Dillard added.

“Who?” Wells asked.

Dillard hesitated. “Everyone.”

Wells nodded.

“Does anyone disagree with it?” Wells asked.

Dillard considered. “Not disagree,” he said. “Some would phrase it differently.”

“But they’d sign it,” Wells said.

Dillard nodded. “Yes.”

Wells looked at the paper again.

“Did anyone ask what I thought?” Wells asked.

Dillard shook his head. “They figured you’d decide.”

That, Wells thought, was the most honest thing anyone had said all week.

________________________________________

He took the statement with him when he left the office.

Not to file it.

Not to sign it.

Just to see where it belonged.

Mrs. Lottie Ames was sitting on the bench outside the church, hands folded, gaze unfocused in the direction of the hills.

“You’re early,” she said.

“I came with something,” Wells replied.

She did not look at the paper.

“You’ve already been given it,” she said.

“Yes,” Wells replied. “I want to know what happens if I don’t use it.”

Mrs. Ames smiled faintly. “Then nothing happens.”

“That’s not true,” Wells said.

She tilted her head. “Nothing new happens.”

Wells held the paper out slightly.

“This says he left,” Wells said. “It says no one helped him. No one stopped him.”

“Yes,” she replied.

“You know that isn’t the whole truth,” Wells said.

Mrs. Ames looked at him now. “You know the whole truth isn’t usable.”

Wells folded the paper again.

“What did Samuel Kline finish?” he asked.

Mrs. Ames did not answer immediately.

When she did, her voice was quiet.

“He finished belonging to anyone else’s problem.”

Wells absorbed that.

“That’s not a crime,” he said.

“No,” she agreed. “It’s a condition.”

________________________________________

Wells went next to the livery.

Walter Finch was brushing a horse that didn’t need it.

“They gave you a way out,” Finch said, without looking up.

“Yes,” Wells replied.

“You going to take it?” Finch asked.

Wells watched the brush move through the animal’s coat, steady and repetitive.

“If I do,” Wells said, “what happens to the rest of it?”

Finch shrugged. “It stays where it is.”

“And Samuel?” Wells asked.

Finch stopped brushing.

“He’s already stayed,” Finch said. “Just not here.”

Wells nodded.

________________________________________

At the boardinghouse, Nora Bell read the paper without touching it.

“They always do this,” she said.

“Do what?” Wells asked.

“Give you something you can live with,” she replied.

“And you?” Wells asked.

Nora met his gaze. “I can live with a lot,” she said. “But I won’t carry it for you.”

Wells folded the paper carefully and placed it back in his coat pocket.

________________________________________

That evening, Wells sat alone in his office.

The lamp burned low.

He opened the desk drawer and removed the notepad.

He placed the folded statement beside it.

Two objects.

One precise.

One incomplete.

He understood now that the town was not asking him to lie.

It was asking him to choose which truth was allowed to stand.

Wells picked up the statement.

He did not sign it.

He did not tear it up.

Instead, he slid it into the back of the notepad and closed it there, hidden but present.

Outside, Dry Haven settled into the evening as if a decision had been made.

Wells leaned back in his chair.

He knew the town would wait only so long before it decided whether he was finished too.

Chapter Eight — What Was Filed

Sheriff Martin Wells woke before daylight and did not make coffee.

He dressed in the dark, pulled his coat on, and stood at the small table long enough to confirm that the room held no decisions he hadn’t already made the night before. The notepad sat where he had left it, the folded statement tucked into the back like a pressed leaf—out of sight, not forgotten.

Outside, Dry Haven was quiet in the way it became quiet when nothing new was expected of it.

Wells unlocked the office and lit the lamp.

The desk was bare except for the forms stacked neatly to one side. Incident reports. Departure notices. Property acknowledgments. Paper designed to absorb things without asking what they weighed.

He sat and pulled one form free.

He read the header.

He read it again.

Then he set it aside untouched.

Wells opened the notepad instead.

He turned slowly through the pages, not searching for information, but confirming sequence. Names appeared and reappeared. Phrases corrected themselves. Time bent slightly where it had been allowed to.

He stopped at the first page.

Samuel Kline.

Still alone. Still undecided.

Wells took a fresh sheet from the stack and placed it in the typewriter.

He typed carefully.

Not what had happened.

What hadn’t.

No body recovered.

No witnesses to violence.

No evidence of forced departure.

No formal complaint filed.

He removed the page and read it.

Everything on it was true.

Everything missing from it mattered.

He signed the bottom.

Not with flourish.

Not with hesitation.

Just enough pressure to be legible.

He folded the paper once and placed it in the outgoing file.

It was not a conclusion.

It was a boundary.

________________________________________

Deputy Frank Dillard arrived as the sun began to thin the dark.

“You finish it?” Dillard asked.

“I filed what I could,” Wells replied.

Dillard nodded. “That’ll do.”

“For whom?” Wells asked.

Dillard hesitated. “For the town.”

“And for me?” Wells asked.

Dillard looked at him. “That depends how long you plan to stay.”

Wells did not answer.

________________________________________

By midmorning, the town behaved as if the matter had passed its proper hour.

The horse was sold.

The boardinghouse room was rented.

The well yard remained smooth.

No one asked Wells what he’d written.

They did not need to.

Mrs. Lottie Ames passed him on the street and nodded once.

“That’ll hold,” she said.

“For now,” Wells replied.

She smiled faintly. “That’s all anything ever does.”

________________________________________

Wells returned to the boardinghouse one last time.

The room upstairs was empty now.

The bed had been remade.

The window wiped clean.

The chair stood where it belonged.

Only the boot remained.

Wells crouched and lifted it.

It felt heavier than it should have.

Not with meaning.

With decision.

He carried it downstairs.

Nora Bell watched him from the counter.

“You’re taking that?” she asked.

“Yes,” Wells replied.

She nodded. “Good.”

“Why?” Wells asked.

“Because if it stays,” she said, “it becomes something else.”

Wells carried the boot outside.

He did not bury it.

He did not burn it.

He placed it in the evidence locker and closed the door.

He wrote the item number on a small tag and tied it loosely.

Not secured.

Not lost.

Just accounted for.

________________________________________

That afternoon, Wells packed his notepad into his coat and walked the edge of town where the road bent east.

He stood there longer than necessary.

Nothing called him forward.

Nothing asked him to turn back.

He understood now that Dry Haven had not asked him to solve anything.

It had asked him to decide what kind of silence it would keep.

Wells turned and walked back.

He would stay—for now.

But the town had learned something too.

It had learned how much could be finished without him.

And Wells knew that one day, perhaps sooner than later, Dry Haven would decide whether he belonged to its past tense as well.

He opened the notepad one last time and wrote a final line beneath the name.

Not finished.

He closed the book.

Chapter Nine — What Was Not Said

Sheriff Martin Wells did not announce his departure.

He packed early, before the street had fully decided what kind of day it intended to be. The office door remained unlocked behind him, the desk cleared except for the ordinary papers that could be mistaken for attention. The evidence locker stayed shut. The tag on the boot remained loose.

Nothing required ceremony.

Outside, Dry Haven moved around him without adjusting. Doors opened when they always did. A wagon crossed the street at its usual hour. Someone swept a porch that did not need it.

Wells stopped once at the edge of town where the road bent east.

The ground there was firm. Whatever had been pressed into it had either lifted again or been smoothed away. He could not tell which, and he no longer needed to.

He reached into his coat and removed the notepad.

He opened it to the first page.

Samuel Kline.

The name still stood alone.

No dates.

No conclusions.

No signature.

Wells closed the notepad and held it for a moment longer than he had to. He considered leaving it behind—in the office drawer, or on the desk, or somewhere it could be discovered later and mistaken for instruction.

He did not.

He placed it back in his coat and turned.

As he walked, he passed Mrs. Lottie Ames sitting on her bench near the church. She did not look up.

“You’ll be back,” she said.

Wells stopped but did not turn.

“Maybe,” he replied.

“That’s enough,” she said.

He continued on.

At the boardinghouse, Nora Bell stood in the doorway, hands folded, watching the street rather than him.

“I won’t ask,” she said.

“I wouldn’t answer,” Wells replied.

She nodded once.

Walter Finch raised a hand from the livery without stopping his work. Deputy Dillard watched from the office window and did not wave.

No one followed.

That was the clearest answer of all.

When Wells reached the bend in the road, he paused once more—not to look back, but to confirm that the road did not care which direction he chose.

It didn’t.

He stepped forward and felt the town release him without resistance.

Behind him, Dry Haven did not close ranks. It did not seal itself. It simply continued—corrected, aligned, intact.

Later, someone would say Samuel Kline had passed through.

Later still, someone else would say he had finished.

No one would be wrong.

Wells walked until the town no longer shaped the air around him.

He did not write another word.

And Dry Haven kept the silence it had chosen, which was not the absence of truth—but the refusal to speak it aloud.

—End—