Chapter One

Calvin “CB” Thomason was forty-four years old in the summer of 1961, though no one would have guessed it correctly. He walked with the shortened patience of a man who had been hurt often enough to stop arguing with pain, and his face had settled into the kind of stillness that came from long exposure to wind, dust, and other people’s expectations. He had been riding bulls for more than twenty years on a circuit that ran through west Texas, eastern New Mexico, southern Colorado, and one stubborn stop in Oklahoma that refused to die. The circuit knew him. It did not take care of him.

CB rode better than he walked. That was the first thing people noticed and the last thing they forgot.

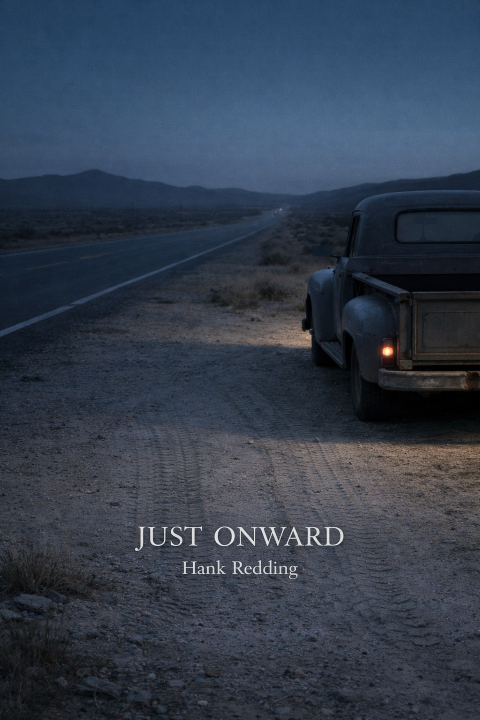

He arrived at the fairgrounds outside Clayton just before noon, his truck coughing once before shutting down for good. The paint had faded to a color that no longer matched itself from panel to panel, and the right fender carried a crease from a fence post he’d misjudged years back. The truck was older than most of the riders and carried more miles than anyone bothered to count anymore. CB sat for a moment with his hands on the steering wheel, letting the stiffness loosen in stages. He had learned not to rush that part. Rushing made things tear.

A St. Christopher medal hung from the rearview mirror on a length of twine, clicking softly as the engine settled. CB didn’t look at it. He never had.

He stepped down carefully, favoring nothing obvious. His left knee clicked when he straightened. He waited for it to settle before moving on, eyes already taking stock of the grounds.

The rodeo was small. It always was. Two borrowed bleachers, boards soft at the edges, nails working themselves loose from years of heat and cold. A stock trailer with one door that didn’t latch unless you lifted it just right. Bare bulbs strung from extension cords hummed faintly in the afternoon light. Someone had chalked a schedule on a piece of plywood and then smudged it with the side of their hand.

CB paid his entry fee in cash—crumpled bills folded too many times—and did not wait for a receipt. He never did. The money mattered. The paperwork didn’t.

Someone called his name. Not loudly.

“CB.”

He nodded once without turning.

Ruth Calder stood at a folding table near the chutes, already writing. She wore the same wire-frame glasses she’d worn for years, one arm bent slightly where she’d tried to fix it herself. She was forty-two and had been keeping time for rodeos since she was twenty-five, which meant she trusted clocks less than most people trusted memory. She knew how long eight seconds actually were. She also knew how much the rodeo owed the ambulance service and which riders still hadn’t paid last month’s fees.

A small photograph was taped to the underside of the table, turned so only she could see it—a man on a bronc, frozen mid-kick, dust lifting behind him. She never touched it while people were watching.

She had known CB for fourteen years and had never once asked him what the B stood for.

“You riding today?” she asked, pencil already moving.

“If I draw,” CB said.

Ruth marked something down, then checked the list once more. “You’ll draw.”

That wasn’t optimism. It was arithmetic.

CB walked the pens without stopping, his eyes doing most of the work. He didn’t touch the rails. He didn’t lean. He watched the bulls breathe, watched their feet, watched the way one of them favored a hind leg without meaning to. Another pawed left first every time, scraping a shallow groove in the dirt. A red brindle shook his head slowly, as if bothered by something no one else could see.

CB had learned a long time ago that animals didn’t lie unless people forced them to.

Behind him, a group of younger riders had gone quiet.

They knew who he was. Everyone did, in the way people knew about storms that passed through the same counties every year. There were stories about CB—bar fights that ended before anyone could remember how they started, a man once carried out of a pool hall with his jaw set wrong after asking a question that wasn’t his to ask. There were also stories about women and kids and bartenders who hadn’t had to handle things themselves because CB had stepped in.

No one ever told those stories loud.

CB didn’t look at the young riders, but he knew who was watching and why. He didn’t mind it. He needed it.

He believed—quietly, stubbornly—that competition kept a man honest. That if the sport softened, if the riding became forgiving, then the wrong men would start winning. CB had no interest in winning something that asked nothing back. He taught when he could, corrected when asked, and rode because teaching didn’t pay enough to replace riding.

He was broke in ways that couldn’t be explained cleanly and sore in ways that no longer improved.

A boy stepped forward from the group, eighteen or nineteen at most, hat still stiff with store-bought shape, rope coiled too carefully. CB saw the mistake in the way the kid stood—confidence ahead of judgment, weight set where it couldn’t adjust fast enough.

The boy hesitated. “Mr. Thomason—”

CB turned slowly.

“CB,” he said.

The boy nodded, swallowed, and didn’t finish the question. He stepped back into line, embarrassed, eyes fixed on the dirt.

CB watched him go, then looked back to the pens.

Lyle, the regular bullfighter, leaned against the arena wall, stretching his shoulders and waiting, his eyes never quite leaving the stock.

CB had learned something twenty years earlier, in cold water that moved faster than it looked, and he had carried that knowledge ever since. It hadn’t made him wiser. It had only made him careful about what could and couldn’t be held.

When Ruth called his name for the draw, CB didn’t hesitate.

He never had.

Chapter Two

The canal was not marked.

It didn’t need to be. Everyone local knew where it ran, the way people knew where the ground dropped off near a familiar road. The dirt along its edge was always packed harder, scoured by runoff and boots, pale even after rain. It was late, the kind of late that followed a rodeo without celebration—coffee instead of liquor, dust still clinging to cuffs and collars, the quiet fatigue that made men careless in small ways.

It was 1942. CB had been twenty-four then, riding hard, still strong enough that pain arrived late and left early. He remembered the night clearly because nothing about it had tried to be memorable. The rodeo had been small even by their standards. A few borrowed bleachers. Bare bulbs strung from extension cords. Someone selling paper cups of coffee from a folding table. Talk of the war drifted through the crowd the way weather did—present, unavoidable, but not yet personal.

A pickup turned too wide near the bank.

The dirt gave way without warning—not all at once, just enough. The truck slid forward, nose-first, tires spinning uselessly, and tipped into the water like something obeying gravity rather than panic. Headlights cut briefly across the canal wall, then vanished.

There was no shouting at first.

The canal was cold and fast, fed by runoff that moved with purpose. It did not splash the way rivers did. It filled. Water climbed the cab in steady increments, indifferent to speed or strength.

CB was moving before anyone said his name.

He didn’t take off his boots. He didn’t think to. He went in the way men did then—directly, without inventory. The water hit him hard enough to steal his breath and replace it with pressure. It burned his chest, flattened sound. He came up once, gasping, then went under again, kicking for the cab.

The door wouldn’t open.

CB tried twice before understanding why—not because it was latched, but because the water had already taken the space it needed. He braced himself against the frame and forced it the other way, metal bending just enough to give. Water rushed in all at once, flooding the cab, killing what little light there had been.

Inside was Earl Donnelly, nineteen years old, hired help from two counties over.

Earl had ridden one bull that night and stayed on just long enough to matter. He’d talked earlier about finding steady work after the season, maybe down near Lubbock, where his aunt lived. His legs were pinned awkwardly under the dash where the cab had folded, his body held in place by weight rather than restraint. His eyes were open. One hand floated near the steering wheel, not reaching for anything.

CB got his arms around him and pulled.

The body did not move.

He shifted his grip, planted his boots against the floorboard, and pulled again until the water burned in his chest and his arms began to shake. He cut his forearm on torn metal and didn’t feel it. He wedged himself tighter, one shoulder pressed hard against the frame, and lifted Earl’s head above the rising water as long as he could.

He counted without numbers.

Not seconds. Not breaths. Just the effort required to keep Earl’s face clear. He felt the strength leave the boy in stages he would remember later—not all at once, but gradually, like something loosening its hold.

Earl looked at him once.

That was the part CB never found a way to set down.

When CB came out of the water, it was alone. He dragged himself onto the bank and lay there long enough to draw breath again, water running out of his sleeves and boots, the canal continuing past him as if nothing had been interrupted.

They got Earl out minutes later.

It took three men, a rope, and more effort than anyone expected. Someone slipped on the bank and cursed softly. By the time they laid Earl on the dirt, his body was heavy in the wrong way, water running from his mouth and sleeves. A local doctor—still smelling faintly of coffee and cigarettes—knelt beside him and tried the things he knew how to try.

They worked without speaking.

Pressing.

Lifting.

Waiting.

No one called it CPR. No one named it anything.

When it became clear it wouldn’t change, they stopped.

No one blamed CB.

Someone said, quietly, “He did everything.”

CB sat apart from them, water draining from his boots, his forearm stinging now that the cold had eased. His hands shook in a way he didn’t recognize. He did not argue. He had already learned something, though he didn’t yet have words for it.

Some things could be reached.

Some things couldn’t.

The canal kept running.

Chapter Three

Tommy Raines was eighteen years old and already running out of time, though he didn’t yet know how to measure it. He stood just under six feet, lean from work rather than training, and wore a felt hat that still held its factory crease when he took it off. He had been on the circuit for three weeks—long enough to learn the order of events and not long enough to understand what survived them. He trusted his rope more than his hands and believed, quietly and stubbornly, that staying on long enough would eventually make him belong.

He came from outside Tucumcari, New Mexico, from a place that didn’t show up on most maps unless you knew where to look. His father worked section crews for the railroad when there was work and hauled hay when there wasn’t. His mother kept a house that never quite felt settled, waiting for news that didn’t come often enough to count on. Tommy had grown up around animals that answered to weight and patience, and he assumed men worked the same way.

He was wrong about that part.

Tommy had learned to ride on borrowed stock and borrowed advice. He slept where he could—sometimes in the back of a truck, sometimes on a cot in a barn—and washed his shirt in motel sinks when he had a dollar left over. He listened more than he talked, watched men he couldn’t yet imagine outlasting, and copied what seemed to work without understanding why. He hadn’t been bucked off badly enough to respect how fast it could happen. He had been hurt just enough to think he understood pain.

CB noticed him early.

Not because Tommy was loud or reckless, but because he wasn’t. Because he stood too straight when he waited and shifted his weight carefully, as if afraid of wasting it. Because he coiled his rope with more care than experience required, checking the lay of it twice before setting it down. Because he watched the pens the way men watched something they intended to return to.

CB said little to him at first. A correction here. A word about timing. Nothing that sounded like encouragement. He showed Tommy where to stand when the bull was loading, how to keep his feet clear of the gate, when to wait instead of forcing the rope. Tommy took it seriously anyway, which wasn’t the same thing as hearing it correctly.

They spoke once, properly, near the chutes.

The afternoon had gone thin and quiet, the way it often did before the draw. Men leaned against rails or sat on overturned buckets, passing time without acknowledging it. Tommy stood close enough to CB to be heard without raising his voice.

“You ever get scared?” he asked.

CB looked at him for a long moment before answering.

“Every time,” he said. “If you don’t, you’re not paying attention.”

That was all.

Tommy nodded, absorbing it the wrong way. He took it to mean fear was something you rode through—another thing to outlast, another measure of toughness. He didn’t yet understand that fear was something you learned to live alongside, something that stayed useful if you let it.

When his name came up on the board, there was no cheer. Just a shift in posture among the men who knew how to read draws. Someone murmured the bull’s name and then stopped talking. The bull wasn’t mean. It was heavy and late and had learned to wait.

Tommy rolled his shoulders once and stepped toward the chutes.

CB watched from the rail.

He saw the setup immediately. Saw the way Tommy adjusted his rope, resetting it a fraction tighter than he needed to. Saw the tail lie just a bit too straight in the resin. Saw the hat come off clean when Tommy nodded to the chute hand, the felt still stiff enough to hold its shape.

That worried him more than if it hadn’t.

CB opened his mouth once.

Then closed it.

There were limits to what could be taught. Some things only showed themselves under weight.

The gate opened.

Chapter Four

The bull was named Crosscut, which meant nothing and suggested less. He was not known for malice or flair. He was heavy through the shoulders and patient in a way that confused younger riders. He did not explode. He waited, then acted.

Crosscut wasn’t named by a committee.

He wasn’t named for how he bucked.

He was named because of one mistake.

Years back—no one remembered exactly where, only that it was early morning and cold—Crosscut was still green. Not mean, just strong and undecided. A stock hand went into the pen alone, doing what he’d done a hundred times before, moving too close, trusting habit.

Crosscut shifted sideways instead of forward.

That was all.

The man found himself cut off from the gate, pinned by weight and angle rather than aggression. Crosscut didn’t charge. He just stood there, head low, deciding. Long enough for the man to understand he had misread the situation.

There was no straight line back.

The only way out was diagonal, across the pen, slipping between rail and animal, crossing where he shouldn’t have had to. He made it—barely—climbed the gate wrong, tore his shirt, scraped an arm, left blood on the wood.

Enough to be embarrassed.

Enough to be remembered.

Someone said later, laughing because laughter comes easy after survival,

“Had to crosscut his way out of that one.”

The name stayed.

Not because it was clever.

Because everyone knew what it meant.

Tommy Raines drew him without comment.

At the chutes, men moved the way they always had—checking ropes, testing gates, passing the rosin bucket hand to hand. The gate latch stuck once and had to be lifted just right. Someone spat into the dirt and wiped his mouth with the back of his sleeve. The announcer’s voice drifted in and out through the loudspeaker, uneven and thin.

CB stood back from the rail, his arms folded, watching the small adjustments that mattered more than courage.

Tommy set his rope once, then reset it. He checked the lay of it against the bull’s flank and tugged lightly, as if testing a knot he already trusted. The tail lay straight in the resin, too clean. His hat was off now, resting on the fence post, the felt still stiff enough to hold its shape.

CB saw the mistake.

Not a large one. Not something you could point to and name. Just a fraction of timing—a confidence that assumed the bull would move the way bulls usually did. CB shifted his weight, felt his knee click, and said nothing.

Advice given too late only sounded like regret.

Ruth called the ride into readiness. She glanced at the clock once and then away. The announcer cleared his throat and read Tommy’s name, mispronouncing it slightly, then corrected himself. There was a cheer—polite, brief—then quiet.

The gate opened.

Crosscut stepped out once, heavy and deliberate, hooves striking the dirt with a sound that carried farther than it should have. He dropped his shoulder and turned late. Tommy stayed with him through the first movement, adjusted cleanly, rode where the bull was rather than where he expected him to be.

It looked right for a moment.

Long enough to count.

Then Crosscut changed his mind.

The turn came tighter than expected. The hind leg came through where space should have been. Tommy felt the slip before it fully happened, his balance shifting just enough to register. He came off without drama, hit the ground on his side, and slid once before stopping.

There was no crack.

No obvious wrongness.

Crosscut’s back foot came down once.

Hard.

The bullfighter was there immediately, drawing Crosscut away, waving his arms wide, putting himself where the bull could see him. Crosscut moved off without protest, head low again, as if the work were finished.

The arena went quiet in the way it did when people were deciding what they were seeing.

CB was already moving.

He dropped into the dirt beside Tommy and knelt carefully, his movements precise, practiced. He put a hand at the boy’s neck, another at his chest, listened with his fingers the way he had learned to do long before anyone taught it properly.

Tommy did not speak.

His eyes were closed.

His chest lifted unevenly, one side lagging behind the other.

“Don’t move,” CB said, though he didn’t know who he was saying it to.

Someone brought the stretcher too fast. CB waved it back once, sharply, his voice cutting through the noise that had started to rise at the edges. He adjusted Tommy’s head, kept his spine aligned the way he knew it should be, felt the body resisting him in small, worrying ways.

Lyle hovered close, doing his job without being asked, watching the bull’s position even after it no longer mattered. Ruth had already left the table, her pencil dropped where it fell, the clock still running.

The ambulance took longer than it should have. It always did. The dirt road beyond the fairgrounds swallowed sound, then returned it too slowly.

By the time they loaded Tommy, his breathing hadn’t improved. CB climbed down from the rail and stood back, dust on his hands, his shirt torn at the elbow where the ground had taken it.

No one spoke.

The announcer cleared his throat and said something about a delay. His voice sounded wrong in the quiet. The crowd shifted, uncertain what they were allowed to feel.

CB watched the ambulance pull away until it was out of sight.

He did not move.

Later, someone would say he did everything right.

He already knew what that sentence meant.

Chapter Five

They closed the arena without saying they were closing it.

Hank Toliver walked the length of the rail once, hands in his pockets, and said quietly to no one in particular that it was enough for the night. He didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t look at anyone when he said it. No one argued. The gate crews loosened where they stood, work stopping mid-motion. One man finished tightening a bolt he no longer needed to tighten. The stock trucks stayed where they were. Dust settled into the places it always did.

Ruth Calder wrote down the time the ambulance left.

She wrote it neatly, the way she always did, then drew a line beneath it and set her pencil down beside the book. The page did not look finished, so she didn’t close it. She had learned to leave space. There would be more to add later. There always was.

She checked the clock again, then stopped herself and folded her hands on the table. Someone asked her if they should pack up the timing equipment. She nodded without looking up.

Sheriff Ward arrived after the worst of it was already over.

He took his hat off when he stepped onto the dirt and held it at his side while he asked the questions he needed to ask. His voice stayed level. He knew most of the names already, and that made him slower about writing them down. He spelled them twice anyway. He asked about the gate. He asked about the bull. He asked who had reached the boy first.

“Me,” CB said.

Ward nodded. He wrote that down and did not ask anything else about it. He paused once, as if considering another question, then moved on.

The crowd drifted off in small groups, unsure whether leaving was disrespectful or staying was worse. A family with two young boys stopped near the fence and waited for someone to tell them it was all right to go. No one did. They left anyway.

Someone gathered a hat from near the chute and set it on the rail. The felt was scuffed now, the brim bent where it had struck the dirt. No one claimed it. It stayed there longer than it should have, then longer still.

The announcer packed up his microphone and coiled the cord carefully, as if care alone might be enough. He said nothing more than he had to. When he spoke at all, his voice sounded out of place.

CB sat on the tailgate of his truck and waited for the shaking to pass.

It came and went in waves. Not fear. Not grief. Recognition. His hands steadied eventually. They always did. He wiped them on a rag he kept folded in his back pocket and looked at the smear of dirt and dried blood left behind. He folded the rag again, slower this time, and put it back.

Lyle came over and stood nearby without speaking. He leaned his weight onto one leg, then shifted it, as if the ground beneath him were still unsettled. After a while he said, “You did what you could.”

CB nodded once.

Ruth approached later with the entry money in an envelope. She held it out without comment, her fingers lingering on the edge for just a moment before letting go. CB took it and did not open it. He tucked it into his jacket and stood, joints protesting in familiar ways.

“You staying on the circuit?” she asked.

“For now,” CB said.

That was not reassurance. It was accounting.

They loaded the remaining stock in the dark. A gate creaked where it always creaked. Someone missed a latch the first time and had to redo it. Crosscut went up the ramp without resistance, hooves steady, head low, the sound of his weight changing as he stepped from dirt to metal. The trailer door shut with the sound of metal finding its place. Hank checked the latch twice and rested his hand there a moment longer than necessary.

When the lights finally went out, the arena looked smaller than it had earlier. Empty. Unremarkable. The kind of place that forgot things quickly.

CB drove until the fairgrounds were out of sight, then pulled over on the shoulder of the road. He sat there with the engine running, hands resting on the wheel, watching insects throw themselves against the windshield and slide down without leaving much behind.

The night pressed in around the truck, quiet enough that he could hear the engine’s uneven idle and the faint click of cooling metal.

He thought of the canal once, uninvited.

He thought of the boy’s hat on the rail.

He did not think about stopping.

When he started the truck again, it was because there was nowhere else to be.

Chapter Six

The next rodeo was two towns over and smaller.

It always was. The circuit didn’t shrink dramatically—it wore down. Bleachers were replaced one board at a time, never evenly, never all at once. These were half the size and twice as tired, boards soft underfoot, nails showing where repairs had been made without concern for how they looked. Someone had painted over old advertisements with the wrong shade of white. You could still read the earlier names through it if you stood close enough.

The air smelled of manure and diesel, the two odors never quite separating. The announcer was different—a younger man with a higher voice who leaned too hard on his microphone. The bulls were not. CB recognized three of them immediately. He didn’t bother remembering the others. The circuit did not acknowledge loss the way families did. It adjusted.

CB arrived late and left early. No one remarked on it, which told him more than comment ever would have.

He paid his entry fee in cash again, folded smaller this time. The man at the table counted it twice, not because he distrusted CB, but because that was the habit now. Everything got counted twice. CB signed his name and moved on before the ink had time to dry.

Tommy Raines’ name did not appear on any board.

CB noticed it immediately, the way you noticed a missing tooth when someone smiled. No one asked why. No one leaned in or lowered their voice. The absence carried its own explanation. In places like this, explanation was considered unnecessary, sometimes rude.

A younger rider wore a hat with a brim still too sharp, the felt not yet broken in. Not the same hat—just the same mistake. CB watched him adjust it once, crease still too sharp, crown too stiff. He looked away before the thought could finish forming.

Entry fees were lower here. The money was worse. CB rode once and finished where he always did—high enough to matter, not high enough to celebrate. He collected his check without looking at the amount. It would cover gas and a room if he was careful. It would not carry him further than that.

Between events, CB leaned against the rail and watched the order of things continue. A bullfighter he didn’t know well limped slightly on his left side, favoring it without comment. A gate hand argued briefly with a rider about rope placement, then gave up and let it go. A woman sold coffee from a folding table, the pot burned down to bitterness by mid-afternoon.

Someone mentioned a wreck from two seasons back, pointing vaguely with a cup. Someone else nodded and said they remembered. They didn’t. They remembered the shape of it, not the person.

After CB rode, a young rider asked him a question about hand placement. The boy’s fingers were raw, split in places where tape hadn’t held. He listened closely, nodding too quickly.

CB answered him.

He showed him where the pressure should sit, how to let the rope settle instead of forcing it. He didn’t talk about fear. He didn’t talk about outcomes. He said what needed to be said and stopped.

That was all.

The boy thanked him and moved on. CB watched him go, then turned back to the pens. He noticed how often he did that now—watching someone leave instead of staying engaged. He didn’t assign meaning to it. He had learned what happened when you did that.

The rodeo ended without ceremony. No announcements beyond what was necessary. No lingering.

CB loaded his gear slowly. His hands ached in a way that didn’t quite rise to pain. He took longer pulling one boot off than the other and did not comment on it. He folded his shirt carefully before setting it on the seat, then unfolded it again and used it to wipe dust from the dashboard.

He thought, briefly, about calling ahead to the next town. Then he didn’t. Showing up was still enough.

As he drove out, he passed a sign someone had nailed crookedly near the road—RODEO TONIGHT—the arrow pointing nowhere useful. He watched it disappear in the mirror and didn’t try to remember the name of the town.

The circuit moved on.

Chapter Seven

In eastern New Mexico, outside a town that smelled faintly of alfalfa and diesel, CB watched a boy make a mistake he recognized.

The rodeo grounds sat low, tucked against a stretch of land that looked like it had been waiting for something longer than anyone remembered. Wind moved through the grass unevenly. A grain elevator stood a mile off, its paint faded to a color that no longer named itself. The air carried the smell of cut hay and fuel, sweet and sharp in alternating breaths.

CB leaned against the rail and watched the boy work his rope.

The boy was maybe twenty. Strong in the way young men were strong before experience taught them how much of it was borrowed. His shoulders were square, his stance confident without being flashy. He moved quickly, tying and retying as if speed itself were proof of readiness.

But the knot was wrong.

The tail of the rope was tucked, but the bite hadn’t set deep enough into the resin. It was a friction mistake—one that only mattered once the world started spinning.

Not dramatically wrong. Not careless. Just off by enough that it would slip under load, change the timing by a fraction, shift weight where it shouldn’t go. CB saw it immediately. So did Hank Toliver, who glanced over once, met CB’s eyes briefly, and waited.

CB felt the recognition settle in his chest.

He’d seen this before. Not the boy—not this one—but the shape of it. The certainty. The trust in habit before habit had earned it. He thought of Tommy Raines adjusting his rope with the same careful confidence. He thought of the way the hat had come off clean when Tommy nodded.

CB opened his mouth.

Then closed it.

He told himself there were reasons. The boy hadn’t asked. The mistake wasn’t guaranteed to matter. Too much instruction at the wrong moment could be worse than silence. He had learned that, too.

The gate hand called for readiness.

The boy nodded and climbed into position. The knot held—for now. The bull stepped out hard but not malicious, spun once, then twice. The timing went wrong exactly where CB had expected it to. The rope slipped just enough to change the boy’s balance. He came off hard, hit the dirt shoulder-first, rolled clean.

CB didn’t move.

The boy stood up swearing, dusted himself off, and laughed in the way young men did when they realized they were still alive. He raised a hand to the crowd, embarrassed but intact. Someone clapped. Someone else shouted encouragement that sounded more like relief.

CB felt the tension leave his chest slowly, unwillingly.

It surprised him how physical it was. Not relief, exactly—release. Like setting something down you hadn’t realized you were holding.

Later, while coiling rope near the truck, CB watched the boy move around the edge of the arena, replaying the ride in his head. The boy stopped once, retied his rope the same way he always had, then moved on. He didn’t look shaken. He didn’t look changed.

CB finished coiling and set the rope down carefully, aligning it with the others. He was wiping his hands on a rag when the boy approached.

“Shoulda said something,” the boy said.

Not accusing. Just honest.

CB looked at him for a long moment.

The boy’s face was flushed from exertion, eyes bright, the near-miss already turning into something he could tell later without embarrassment. CB recognized that, too. The speed with which danger became anecdote.

“I thought about it,” CB said.

The boy nodded.

He accepted the answer without resentment, which worried CB more than if he hadn’t. Acceptance suggested trust. Trust suggested repetition.

They stood there for a moment longer, neither of them sure what else needed to be said. Then the boy thanked him—out of habit more than necessity—and walked off toward his gear.

CB watched him go.

He noticed how often he did that now—watching someone leave instead of stepping alongside. He did not assign meaning to it. He had learned what happened when you did that.

That night, CB stayed in a room above a bar that smelled faintly of stale beer even with the windows open. The bed sagged in the middle. Pipes knocked as the building cooled, metal contracting in short, uneven bursts. CB lay on his back with his hands folded on his chest, listening.

He counted the cracks in the ceiling the way he sometimes counted breaths. Not to calm himself. Just to keep time.

He thought of Earl Donnelly in the canal, his body pinned by weight and angle rather than intent. He thought of Tommy Raines’ breathing, shallow and wrong, the way it had refused to improve. He thought of the boy who had walked away tonight laughing, already intact again.

He wondered—not for the first time—how often stepping in changed anything at all.

And how often it didn’t.

How often silence did the same work.

The questions did not argue with each other. They simply sat there, unresolved.

CB rolled onto his side carefully, favoring nothing obvious. He adjusted the pillow once, then again. The pipes knocked one final time and went quiet.

He slept anyway.

Chapter Eight

The final rodeo of the season was held on ground that had been worked too many times.

The dirt was compacted and pale, the kind that didn’t give back once it took something from you. CB noticed it when he walked it, felt it through the soles of his boots. He paused once, shifted his weight, tested it again. The ground held. It always did. He didn’t mention it to anyone.

He did not ride that night. No reason was offered.

No announcement marked the absence. No one asked where his name had gone. The draw moved forward without it, the way things did when space opened unexpectedly. Younger riders filled the gap easily. There were always younger riders. The bulls bucked. The crowd clapped when asked, their attention rising and falling on cue.

CB stood at the rail and watched.

A rider two chutes down was using a rope that had been cut shorter than most, the tail singed and darkened. CB noticed the adjustment without knowing why it bothered him. He looked away before the thought finished forming.

He recognized patterns more than faces now. The way a bull leaned before turning. The way a rider set his feet when he was guessing instead of knowing. He watched for the small hesitations that preceded larger ones, the moments where a man chose to force something rather than wait. He noticed how often those moments went unpunished.

At some point, someone bumped his elbow and apologized too quickly. CB waved it off. The man moved away, embarrassed. CB felt older then than he had all summer. Not weaker. Just more accounted for. Like something had finally been written down that he hadn’t known was missing from the ledger.

When the lights went out, he did not linger.

He walked back to his truck without looking over his shoulder, loaded his gear with the same care he always had, and drove until the fairgrounds were out of sight. The road thinned as it headed west, traffic dropping away until the dark belonged mostly to him. He pulled over once, shut the engine off, and listened to it tick as it cooled.

The night was empty enough to hear it.

He sat with his hands resting on the wheel, watching his breath fog the windshield briefly before disappearing. Somewhere nearby, an insect struck the glass and slid down without leaving much behind. CB didn’t wipe it away. He had learned which marks mattered.

He thought of Earl Donnelly, whose name had not been spoken in years.

He thought of the canal, the way the water had moved with purpose, indifferent to shouting or effort. He remembered the weight of Earl’s body when it stopped responding, the moment when strength gave way to time. He remembered the sentence someone had offered him afterward—He did everything—and how it had sounded then, too early to understand what it would come to mean.

He thought of Tommy Raines, whose name would not last as long.

He remembered the hat on the rail, the way it had been set down carefully, as if care itself could change what followed. He remembered the shallow, wrong breathing, the refusal of the body to correct itself. He remembered how quickly the circuit had adjusted. How absence became explanation without ever being named.

He thought of Crosscut standing where space was supposed to be.

Not charging. Not acting out of malice. Just present, heavy, altering the geometry enough to matter. CB understood that kind of danger better than most. It was the kind you didn’t see until it was already doing its work.

CB started the truck again and drove on.

The road stretched ahead, pale and unremarkable in the headlights. Mile markers passed without registering. Town names appeared on signs and disappeared before he bothered to read them. He did not plan where he would stop. He rarely did anymore. Showing up had been enough for a long time.

Somewhere ahead, there would be another rodeo. Or there wouldn’t.

Either way, the road would be there.

CB kept driving until the land flattened and the sky opened wider than it had any right to. He drove until the ache in his hands settled into something manageable, until the thought of stopping felt heavier than the act of continuing.

He did not know when the last ride had happened. He suspected he never would. There was no moment that announced itself as final. No clean ending. Just the gradual removal of names from boards, the quiet redistribution of space.

That was how most things ended.

As the horizon began to lighten, CB stayed on the road. He adjusted his grip on the wheel, eased his shoulders back into alignment, and let the engine carry him forward.

Not toward anything in particular.

Just onward.