Part I — What Lingered

The dust came early that year.

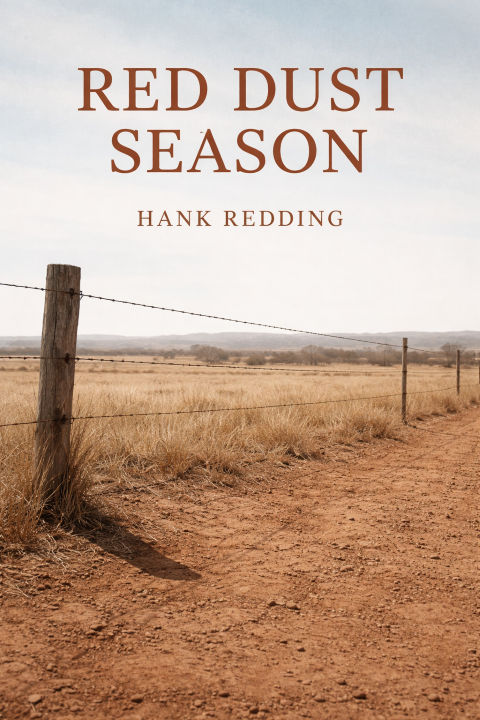

By mid-May it had already crept into the fence lines, gathered along the edges of the road like it was waiting for something to pass. It rose easy under tires, hung longer than it should’ve, settled back down slow and fine. Red dust. The kind that didn’t blow away so much as relocate.

He noticed it first in the mornings, when the sun hit the flats low and turned the whole valley the color of old brick. It coated the gate chains, dulled the shine on the water tanks, worked its way into the seams of his boots. You could wash it off your hands and still see it an hour later, ghosted into the creases of your skin.

The ranch hadn’t changed much. The house leaned the same way it always had, porch boards sagging near the steps, screen door whining on its hinge. The barn roof still caught the light unevenly where the tin had been patched years apart. The land didn’t care who stood on it. It took whoever showed up and kept moving.

He was up before the sun most mornings. Not because he needed to be—because it was easier than lying there listening to the quiet settle wrong. He drank his coffee black and standing, mug resting against the sink, eyes on the window where the glass had a hairline crack no one ever fixed. Outside, the pasture waited. It always did.

The work was straightforward. Fence checks. Water lines. A sick calf that didn’t look like it was going to make it but did anyway. He fixed what broke and made notes about what would break next. There was comfort in knowing the order of things, even if the order wasn’t kind.

The truck sat near the barn, angled just slightly off square like it had been parked in a hurry and never corrected. It was an older Ford, sun-faded and loud, the kind of vehicle that announced itself whether you wanted it to or not. He used it when he needed to haul feed or pull something stubborn loose. Other times it sat, collecting dust like everything else.

He didn’t think about the truck much. Not in the way people might have expected. It was there. It worked. That was enough.

In town, folks nodded more than they talked. They asked how the cattle were doing. They mentioned the heat. They said things like time sure does move and seems like yesterday, then let the words trail off like they’d run into a fence they didn’t want to climb.

At the feed store, the bulletin board was still crowded with notices that never came down. Church suppers. Lost dogs. A curling photograph of a boy in uniform, smiling too wide, pinned at the corner with a rusted tack. No one touched it. No one asked about it either.

The men who gathered at the café in the mornings all sat the same way now—backs to the wall, eyes on the door. Some of them had come back thinner. Some heavier. Some with a quiet that didn’t lift even after the second cup. They talked about equipment prices, about weather patterns, about how the highway was supposed to get expanded someday.

No one talked about where they’d been.

His mother called once a week, sometimes more. She asked if he was eating right. If he’d fixed the loose step on the porch yet. She told him the neighbor’s boy was getting married, that the preacher’s wife had taken ill, that the garden was coming in late. She didn’t ask certain questions. He didn’t offer answers.

At night, the house settled around him in its own language. Pipes knocking. Wind finding gaps. The distant sound of a truck passing on the highway, heading somewhere else. He slept light and woke early, always a few minutes before the alarm, heart already moving faster than it needed to.

There were things left behind that he didn’t move.

A jacket hung on a hook by the door, sleeves creased where someone had pushed them up instead of taking it off properly. A set of keys lay in a shallow bowl on the counter, never picked up, never put away. In the shed, a box of letters sat unopened, tied with twine gone soft from age and handling.

He told himself he’d get to it when things slowed down.

Things didn’t slow down.

One afternoon, a section of fence gave way along the south boundary. He found it half-collapsed, wire sagging, posts leaning like tired men. It wasn’t dramatic. Just neglect finally adding up. He set to work without thinking, muscles remembering the job even as his mind wandered elsewhere.

By the time he finished, his hands were shaking—not from the effort, but from the pause afterward. That moment when there was nothing left to fix, nothing immediate to do. He stood there longer than necessary, looking out across the field where the dust lay settled and quiet.

The sky was wide. It always was.

He wiped his hands on his jeans, climbed into the truck, and turned the key. The engine caught on the second try, rough at first, then steady. He didn’t turn on the radio. Didn’t roll the windows down. He just sat there a moment, foot on the brake, listening to the idle.

The dust lifted when he pulled away, rising behind him in a long, patient plume. It followed the road, followed the fence line, followed him until the land dipped and the view opened and there was nothing ahead but more of the same.

That night, the wind picked up. It rattled the windows, carried the smell of dry earth through the screens. He lay awake listening to it move through the pasture, through the barn, through the things that had been left exactly where they were.

Outside, the dust shifted again.

Part II — The Long Middle

The first letter showed up on a Thursday.

It wasn’t a personal letter. It wasn’t even a real envelope in the way mail used to be. It was stiff and official, typed address, government return stamp in the corner, and a warning on the back about forwarding. He stood at the mailbox longer than he needed to, thumb pressed into the paper like he could read through it.

Inside the house, he set it on the table and walked past it twice before he opened it.

The language was clean and bloodless. Dates. Reference numbers. A reminder to respond by a certain time. An apology for inconvenience. The words were arranged like fence posts—straight, spaced, indifferent. The letter wanted something from him, and it wanted it in triplicate.

He read it once, then again, then set it back down and went outside.

The wind was already up, carrying that red dust from the flats, lifting it in ribbons along the road. He walked toward the barn and found himself tightening bolts that weren’t loose, checking hinges that worked fine, picking up tools he hadn’t used. The sun moved overhead and he kept moving with it, staying just busy enough to keep his hands from settling.

By late afternoon he’d fixed nothing and worn himself out anyway.

When he came back in, the letter was still on the table, waiting. The house smelled like stale coffee and sun-warmed wood. He sat down, took a pen from the drawer, and began filling the form in the way you did when you wanted the day to end.

Name. Address. Relationship.

He wrote the relationship carefully. Not because it was hard, but because the pen wanted to wobble. The word looked smaller on paper than it should’ve.

He folded everything back into the envelope, sealed it, and placed it next to the door. He’d take it to town the next morning. He told himself that like it was a plan.

That night, he dreamed of nothing specific. Just movement. Wheels on gravel. A gate swinging open and not closing right. A voice on the edge of hearing, calling a name that didn’t land.

He woke before dawn, heart working like it had somewhere to be.

________________________________________

Town looked the same from the highway.

Same water tower with the paint peeling at the seam. Same row of low storefronts and the same café sign that had been fixed so many times it looked patched together out of other signs. The mountains sat farther back than they seemed from the ranch, distant and blue and uninterested.

He parked outside the post office and sat for a moment with the letter in his lap. The dog tags on the rearview clicked lightly when he shifted. He reached up and steadied them without thinking, thumb running across the stamped metal once, then letting it fall again.

Inside, the post office was cool and smelled faintly of paper and floor wax. A woman behind the counter nodded at him like she knew exactly why he was there, even if she didn’t. He slid the envelope across the counter, watched her stamp it, watched it disappear into the bin with other things people wanted to be done with.

He left before she could ask how he was.

Outside, the air already had heat in it. It wasn’t yet eight in the morning and the sun had that hard shine that promised nothing good. He should’ve driven straight back out to the ranch. There was always something to do. But the truck was pointed toward Main, and his hands turned the wheel like they’d decided for him.

The café was half full. Same men, same stools, same cups lined up like a habit. The talk was low and practical—hay prices, the new irrigation pump someone was saving for, a calf sale down near Dillon. Nobody looked up when he walked in, not right away. They knew his boots. They knew the sound of him.

He took a seat near the end of the counter, ordered coffee, and stared at the sugar caddy without touching it.

One of the men—older, broad shouldered, the kind that didn’t waste words—leaned a little closer.

“They still sending you those letters?” he asked.

The question wasn’t nosy. It was tired. Like he’d been asked the same thing for years by his own life.

He nodded once.

The man grunted like that answered everything worth saying. He went back to his coffee and let the silence sit between them.

A younger guy came in while he was drinking. Not young-young—mid-twenties maybe—but younger than the rest, with a stiffness in his shoulders that didn’t match his age. His hair was cut short, not because it was fashionable, but because it had become the way he understood himself. He scanned the room before choosing a seat, back to the wall.

The older men gave him space. Not respect exactly. Something quieter.

He didn’t know the kid’s name. He’d seen him around since last fall, helping his uncle with fencing, walking out of the bar too early, never staying long enough to relax. The kid ordered coffee and kept both hands wrapped around the mug like he was holding onto heat.

When the waitress passed by, she touched his shoulder gently, like she was trying to remind him he was in a place where people knew his face. The kid flinched anyway.

The man at the end of the counter—someone who’d always been loud—started telling a story about a bull that got loose and knocked down a shed. It was meant to be funny. He was halfway through it when the kid’s mug hit the counter hard enough to splash.

The room went quiet.

The kid’s eyes were fixed on the window, but there was nothing outside but sunlight and dust. His jaw worked, like he was chewing something bitter. Then he stood up without finishing his coffee, left money on the counter, and walked out.

No one stopped him.

The story didn’t continue.

A minute later, the older man beside him cleared his throat, like he was clearing an idea from the room.

“They come back,” he said, not looking at anyone in particular, “but they don’t come back.”

That was all.

The waitress refilled his cup without asking. Her hand shook just slightly. She didn’t spill a drop.

________________________________________

He tried to leave town after that, but his truck idled at the stop sign like it had a question. He could’ve gone home. He should’ve. Instead, he found himself turning down a side street he didn’t use much and pulling into the gravel lot outside the county office.

The building sat squat and brown against the sun, American flag hanging limp on the pole like it had lost interest. Inside, the air was stale and over-cooled, the kind of cold that made the heat outside feel even more brutal when you stepped back into it.

He hadn’t planned to come here. That was the truth. But his feet carried him down the hallway to a small office with a sign in the window—VETERANS SERVICES—letters faded from years of being baked in sun.

A man behind a desk looked up. Late forties maybe, hair thinning, shirt sleeves rolled up. He had that careful manner of someone used to handling other people’s raw edges. He didn’t smile. He didn’t frown either. He simply waited.

“I got a letter,” he said.

The man held out his hand. He took the copy, scanned it, nodded like he’d seen the same paper a thousand times.

“They need confirmation,” the man said. “They always do.”

He nodded again. The words were ordinary, but his throat tightened anyway.

The man slid open a drawer and pulled out more forms, placed them on the desk like setting down tools.

“You got the discharge paperwork?” he asked.

He stared at him.

The man’s eyes softened slightly, not out of pity—recognition.

“Not yours,” he clarified. “His.”

He felt a strange surge of anger at the word his, at the assumption that the paperwork should be where paperwork belonged. In a folder. In a drawer. In a world where the most important parts of a person could be summarized in stamped ink and signatures.

“I don’t know where it is,” he said.

The man nodded like that was the most normal thing in the world.

“Most families don’t,” he said. “It’s alright.”

He set a pencil down between them and pointed to a line on the first page.

“Start here,” he said. “We’ll work from what we’ve got.”

They went through the questions slowly. Name. Date of birth. Service branch. Unit, if known. Dates overseas.

Some he knew. Some he didn’t. Some he knew but couldn’t say without feeling that same tightening in his chest, like something inside him didn’t want to cooperate with the language.

When they got to the part asking for the location of the death, his hand stopped.

He could picture it—not the place itself, because he’d never been there—but the way the letter had described it. A few lines, polite as a grocery list. Regret to inform. Incurred in the line of duty. Your son served honorably.

There was a word in the letter he couldn’t forget. It was a word people used for weather. For mechanical failures. For accidents involving strangers.

He didn’t want to write it down.

The man behind the desk didn’t rush him.

Outside the office window, the flag moved slightly in the air conditioner’s draft, not in any real wind.

Finally, he wrote the word and felt something in him go cold.

When he finished, the man gathered the papers, stacked them clean, and clipped them together.

“This’ll help,” he said. “It won’t make sense, but it’ll help.”

He almost laughed at that. Almost.

Instead, he nodded and stood.

On the way out, he passed a hallway bulletin board covered in notices. Meetings. Assistance programs. A flyer with a phone number you could call if you woke up at night and didn’t know what to do with yourself. A small strip of paper at the bottom read: You are not alone.

He looked at it a long time.

He didn’t tear it down. He didn’t write the number either. He just stood there, hands at his sides, and felt the truth of it and the lie of it occupy the same space.

Then he left.

________________________________________

Back at the ranch, the day was already half gone.

The cattle were clustered under the few trees that gave any shade. The water tanks shimmered in the heat. The barn smelled like old hay and sun-baked lumber. Everything looked normal, which made the wrongness feel sharper.

He found the jacket still on the hook by the door. He touched the sleeve with two fingers, then let it go.

In the shed, he finally dragged the box of letters into the light.

The twine was knotted tight, worn by hands that had tied it and untied it too many times. He sat on a milk crate and stared at it for a long time, listening to a fly buzz against the window.

When he untied the knot, it came loose with a soft snap, like something giving up.

The letters were stacked in uneven piles, paper edges curled, envelopes stained with sweat and handling. Some were unopened. Some had been opened and re-folded so carefully the creases lined up exactly. The handwriting varied—some rushed, some steady. A few pages were smudged where a thumb had pressed too hard.

He didn’t read them all. Not then.

He picked one at random, unfolded it, and stared at the words without letting them enter him. The first line was ordinary—talk of heat, talk of food, talk of missing home. The kind of letter that tried to make a war sound like a job.

Halfway down the page, the handwriting changed slightly, like the writer’s hand had stiffened.

He stopped there.

Outside, the wind picked up again and shoved dust through the cracks in the shed wall. It sifted down over the workbench, the tools, the letters in his lap. He brushed it away once, then stopped bothering.

After a while, he folded the letter back up and set it on top of the stack.

He tied the twine again, but looser.

He wasn’t ready to carry all of it at once.

________________________________________

That evening, his mother called earlier than usual.

Her voice sounded the same as always, but he could hear something tight in it, like she’d been holding her breath for hours.

“You go into town today?” she asked.

He didn’t ask how she knew. The town was small. News traveled the way wind did—through every gap, under every door.

“Yeah,” he said.

A pause.

“You see… anyone?” she asked, and he knew she didn’t mean anyone. She meant the kind of people.

He leaned his shoulder against the wall and looked out the window at the pasture. The dust was settling again, thin and red and inevitable.

“There was a boy at the café,” he said.

She exhaled softly, like the answer hurt and relieved her at the same time.

“They don’t talk,” she said.

“No,” he agreed.

Another pause.

“Your father says you ought to come by on Sunday,” she said, shifting to safer ground. “He wants to fix the fence on the north side before it falls completely.”

He could picture his father saying it like it was about boards and wire only, like it wasn’t about having something to do with his hands. Like it wasn’t about keeping their son close without saying so.

“I’ll come,” he said.

“Alright,” she said, and her voice softened. “Alright.”

He waited, thinking she might say the name. Thinking she might finally step into the open space between them.

But she didn’t.

Instead she said, “Eat something, okay?” like nourishment could patch a hole you couldn’t name.

“I will,” he lied gently.

After he hung up, he stood there in the dim kitchen listening to the quiet settle wrong again.

The truck sat outside near the barn, dusted red in the evening light. The dog tags clicked once when the wind shifted.

He didn’t go out to touch them.

He just watched the sun slide down behind the ridge and let the day end without asking it for anything.

Part III — When Routine Breaks

The break came quiet.

It wasn’t the kind of thing that announced itself with noise or urgency. No crash. No panic. Just a small failure that waited long enough to matter.

He noticed it at first light, walking the north boundary the way he always did. One of the cattle stood apart from the rest, head low, sides heaving just slightly too fast. The fence line beyond it sagged inward where the soil had given way, post leaning like it had finally decided it was tired of pretending.

He checked the wire. It held, barely. He checked the ground. The dirt crumbled under his boot, dry and loose, the red dust deeper here where runoff used to pass before the old culvert collapsed years back.

The cow lifted its head and looked at him, eyes dull, not afraid. Just spent.

He knelt, ran a hand along its flank, felt the heat. Nothing dramatic. No injury he could see. Just something wrong enough to slow everything down.

He stood there longer than necessary, listening to the pasture breathe around him.

By midmorning the heat was already pressing in, the kind that made your shirt cling and your thoughts feel thick. He fetched tools from the barn, hauled a new post from the pile that never seemed to shrink, set about the repair the way he always did—methodical, steady, no wasted motion.

The post hole digger bit into the soil once, twice, then stopped.

Metal rang hollow.

He dug with his hands instead, clearing loose dirt until his fingers scraped against something solid. Old concrete. The remains of a footing poured years ago and forgotten, buried when the fence line shifted and no one bothered to pull it out.

He swore under his breath, not loud. Just enough to let the air know he wasn’t pleased.

He could work around it. He usually did. Shift the post a foot over, adjust the wire, pretend the ground hadn’t won this small argument. But the sag was already there, the weakness visible if you knew how to look. If he didn’t fix it right, the cattle would test it. They always did.

He stood, wiped sweat from his eyes, and stared at the problem like it might change its mind.

The truck sat a short distance away, tailgate dusted red, tires half-sunk into the soft shoulder. He went to it, grabbed the pry bar, leaned his weight into the buried concrete.

It didn’t budge.

He leaned harder. The bar slipped, scraping skin from his knuckles. Blood welled quick and bright, startling against the dirt. He stared at it for a moment longer than necessary, then pressed his thumb into it, smearing it dark.

“Damn it,” he said, louder this time.

The word echoed off nothing.

He tried again. Same result.

Something inside him tightened—not anger exactly, but the sense of a line being crossed. He dropped the bar and stepped back, chest rising too fast, heart working like he’d been running. The heat pressed in from all sides, and suddenly the open pasture felt small.

He sat down hard on the ground, back against the fence post, dust coating his jeans, his hands, his face. The wire hummed faintly behind him, tensioned just enough to sing.

For the first time in months, there was nothing he could fix by staying busy.

The realization hit him sideways, sharp and unwelcome.

He pulled his hat down over his eyes and breathed through it, counting the breaths the way someone had once told him to. In through the nose. Out through the mouth. Slow enough to convince the body it wasn’t dying.

It didn’t work right away.

Images rose without asking. Not clear scenes. Not stories. Just fragments. A folded flag he’d held once, its weight wrong for how light it looked. The sound of boots on gravel behind him when he hadn’t been expecting company. His mother’s hands, shaking just enough to notice when she poured coffee.

He pressed his palms into his eyes until sparks flared.

“Stop,” he muttered, not sure who he was talking to.

The wind picked up, lifting dust into his face, coating his tongue with grit. He tasted iron and dirt and something else he didn’t have a name for.

Eventually, the pounding in his chest eased. The world widened back out, returning to its proper scale. Fence. Field. Sky. Cow watching him like this was all part of the arrangement.

He stood slowly, joints stiff, and brushed himself off.

He didn’t fix the fence that morning.

Instead, he loaded the tools back into the truck and drove toward the house, dust trailing behind him in a long, tired line.

________________________________________

The call came just after noon.

The phone rang twice before he answered, expecting his mother again, or the feed supplier reminding him about an overdue invoice. Instead, a man’s voice filled the line—hesitant, unfamiliar, carrying the careful tone of someone stepping onto uncertain ground.

“This is Paul Henderson,” the voice said. “We met at the café once. I don’t know if you remember.”

He didn’t at first. Then he did. The older man with the quiet way of speaking. The one who’d asked about the letters.

“Yeah,” he said. “I remember.”

There was a pause, the faint sound of breath on the other end.

“My nephew’s been staying with me,” Paul said. “The boy you saw. He’s not… he’s not doing well today.”

The words sat there, heavy but unspecific.

“He doesn’t talk to me much,” Paul continued. “But he asked about you. About the ranch.”

He closed his eyes and leaned his forehead against the wall, the cool plaster grounding him.

“What about it?” he asked.

Paul cleared his throat.

“He said you might understand,” he said. “I told him I’d call.”

Silence stretched between them, long enough to hear the static on the line, the hum of something electrical in the background.

“Alright,” he said finally. “I can come by.”

Paul exhaled, relief plain even through the wire.

“Thank you,” he said. “No hurry. Just… today, if you can.”

He hung up and stood there for a moment, hand still on the receiver.

He hadn’t planned on this. That was the truth. He hadn’t planned on seeing anyone, hadn’t planned on speaking the careful language people used around wounds they couldn’t see. He looked down at his scraped knuckles, the blood dried dark, and felt a strange, steady resolve settle in his chest.

He washed his hands at the sink, watching the red swirl down the drain, disappear.

Then he grabbed his keys and went back outside.

________________________________________

Paul’s place sat on the edge of town, a low house with peeling paint and a yard that hadn’t decided what it wanted to be yet. The nephew sat on the front steps when he arrived, elbows on knees, cigarette burning forgotten between his fingers.

The kid looked up as the truck approached, eyes narrowing slightly, assessing. He stood when the engine cut, stubbed out the cigarette with unnecessary force.

“You don’t have to—” he started, then stopped.

“It’s fine,” he said. “I had to come into town anyway.”

That was a lie, but it was the kind people accepted.

They stood there a moment, neither sure where to begin. The kid’s hands shook slightly, just enough to notice if you were paying attention.

“You want to walk?” he asked.

The kid nodded.

They headed down the dirt road toward the creek, boots kicking up small clouds with every step. The sun beat down hard, no shade to speak of. The kid walked with a stiffness that didn’t match his age, shoulders tight, jaw set.

They didn’t talk at first. They didn’t need to.

At the creek, the water ran low and slow, brownish from runoff, banks cracked where the moisture had pulled away. They sat on opposite sides of a fallen log, the space between them easy, unforced.

The kid took out another cigarette, lit it with shaking hands, took a drag too deep and coughed.

“They tell you to come home,” he said suddenly, voice rough. “They don’t tell you how.”

He stared at the water, watched a leaf spin in a lazy circle before catching on a rock.

“No,” he said quietly. “They don’t.”

The kid swallowed, nodded like that confirmed something.

“My uncle says I should talk,” he said. “Says it helps.”

“Does it?” he asked.

The kid huffed a short laugh.

“Not yet.”

Silence settled again, but it wasn’t heavy this time. Just present.

After a while, the kid said, “You ever feel like the ground’s different? Like it don’t hold you the same way?”

He thought of the concrete buried under the fence line, of soil giving way where it hadn’t before.

“Yeah,” he said. “I do.”

The kid nodded, eyes shining, jaw clenched tight.

They sat there until the sun began to slide lower, until the heat softened just enough to breathe easier.

When they stood to leave, the kid looked at him like he wanted to say something else. Then he shook his head.

“Thanks,” he said instead.

He nodded, understanding that gratitude didn’t always need a speech.

________________________________________

Back at the ranch, the fence still leaned.

He stood there in the evening light, tools in hand, looking at the problem again. The dust had settled for the moment, the air calmer, the sky stretched wide and patient overhead.

He repositioned the post—not where he’d wanted it, but where the ground would allow. He tightened the wire, tested it, felt it hold.

It wasn’t perfect.

It was enough.

As the sun dipped behind the ridge, he wiped his hands on his jeans and looked out across the field. The cow had rejoined the herd, moving slow but steady.

The truck sat nearby, engine ticking softly as it cooled.

For the first time in a long while, he didn’t feel the urge to keep moving just to avoid stopping.

He stood there until the light went, letting the day finish the way it wanted to.

Part IV — What Carries Forward

Sunday came hot and windless.

He drove over early, before the heat could decide what kind of day it wanted to be. His father was already outside when he pulled in, hat low, wire cutters hooked into his back pocket. They nodded at each other the way men do when the work is already understood.

The north fence ran longer than he remembered. Or maybe it just felt that way. The posts leaned at intervals like old opinions, some still holding, some not worth arguing with anymore. They worked without talking at first—stretching wire, tamping dirt, setting things square where they could and accepting the rest.

His father’s hands shook more than they used to. Not badly. Just enough to register. The man noticed him noticing and turned slightly, setting his stance like it didn’t matter.

“You eat?” his father asked.

“Yeah,” he said.

They both knew it wasn’t true. They let it pass.

Around midmorning, his mother came out with a thermos and two cups. She didn’t ask how the fence was going. She didn’t ask anything that would turn the day inward. She poured, handed, waited. The three of them stood there, steam rising, the land breathing around them.

After she went back inside, his father cleared his throat.

“You gonna keep the truck?” he asked.

The question landed careful. Neutral. It wasn’t about transportation.

“I don’t know,” he said.

His father nodded, eyes on the wire.

“Doesn’t owe anyone anything,” he said. “But neither do you.”

They finished the fence by early afternoon. It held better than it had. Not perfect. Enough.

When he left, his mother hugged him longer than usual. She didn’t cry. She didn’t say his brother’s name. She pressed her cheek against his shoulder and breathed like she was memorizing the feel of him.

“Drive safe,” she said.

He did.

________________________________________

The decision came a few days later, the way most real decisions do—not announced, just realized.

He was in the shed, inventorying tools he already knew by feel. The box of letters sat on the bench where he’d left it, twine loose, corners softened by dust. Sunlight slanted through the small window, catching on the metal edges, the paper.

He opened the box and took out three letters. Not the first ones. Not the last. Three from the middle, where the handwriting steadied into something that looked like habit.

He read them this time. All the way through.

They talked about heat. About bugs. About food that tasted like metal. They talked around things more than they talked about them. A line here about a friend who shipped out. A line there about rain that didn’t come. The war stayed mostly off the page, like it knew better than to try and explain itself.

At the bottom of the last letter, the handwriting slanted, rushed.

Tell Dad I fixed the clutch. Tell Mom not to worry. I’ll be home when this is done.

He folded the letters carefully and put them back. He tied the twine again, snug this time. He placed the box on the shelf where the important things went—not hidden, not handled.

Then he went outside and looked at the truck.

The dust on it had settled thick again, red and patient. He wiped a clear streak across the door with his sleeve, exposing the faded paint underneath. The dog tags hung quiet now, barely moving.

He reached up and took them down.

They were heavier than he expected. Or maybe his hands were tired. He held them for a moment, feeling the edges, the stamped letters, the small indentations made by a life reduced to a few facts.

He didn’t put them back.

Instead, he wrapped them in a clean rag and set them in the glove compartment, closed it gently, like that was enough to change the meaning of where they rested.

He drove the truck into town that afternoon and parked outside the feed store. He put the sign in the window—FOR SALE—written neat, nothing dramatic about it. He stood there a moment, then walked away before he could reconsider.

It sold quicker than he thought.

A man from two counties over. Cash. Didn’t ask questions. Appreciated the engine, the condition, the fact that it had been taken care of. They shook hands, filled out the paperwork, did the small ritual of passing something on.

As the truck pulled away, dust rose behind it, same as always. It followed the road, then thinned, then settled.

The space it left felt strange. Lighter. Not empty. Different.

He walked back to his own pickup—the quieter one, newer, less personality to it—and sat behind the wheel. He rested his hands there, felt the shape of something changing, slow enough not to scare him.

________________________________________

The fence held.

Summer deepened. The dust came and went in waves. The cattle moved where they were supposed to. The sick cow recovered enough to rejoin the rhythm of things. Paul’s nephew came by once, helped with a gate, didn’t say much. He stayed long enough to matter.

The letters stayed in their box.

One evening, near the end of August, he drove out to the high field just before dark. He wasn’t running from anything. He wasn’t chasing anything either. He parked and walked the length of the fence, boots scuffing, hands idle.

At the far end, where the land dipped and the view opened, he stopped.

The sky stretched wide, indifferent as ever. The dust lay settled, red and fine, marking where things had passed and where they hadn’t.

He took the dog tags from the glove compartment and held them once more. He didn’t speak to them. He didn’t ask anything of them.

He wrapped them again, tighter this time, and placed them in the fence post hollow, deep enough they wouldn’t rattle loose, shallow enough they weren’t buried. He capped the opening with a flat stone and tamped the dirt around it with his boot.

It wasn’t a marker.

It was the first thing he chose without needing permission.

When he stood, the wind moved through the grass, soft and even. The land accepted the change without comment.

He turned back toward the house, toward the work that waited and the work that would always wait. The dust rose under his steps, then settled again, carrying forward nothing but what the ground chose to keep.

Behind him, the fence held.