Chapter I — The Return

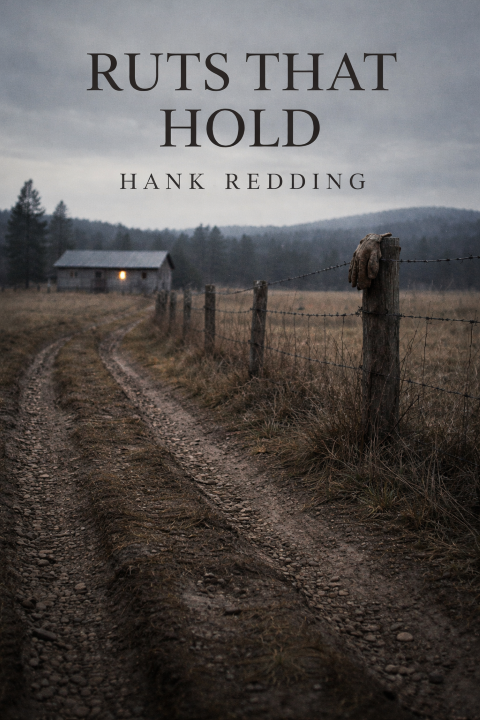

The truck came up the gravel track in low gear, tires crunching the same dry ruts it had left in 1943. He killed the engine at the yard’s edge and sat with the window down, smelling dust and sage that had thickened in the years since. The house leaned under tin that rattled in the wind. A single bulb glowed behind the kitchen curtain, same as the night he’d walked out after their father called him a coward for enlisting.

His brother came onto the porch slow, coat still the one their mother had patched before the cancer took her in ’49. No hat. He stood with hands in pockets, shoulders set the way they’d been when he was twelve and too young for the draft notices that never came for him. The dog under the steps lifted its head once, then dropped it again.

He stepped down, boots settling into ground baked hard. The corral posts sagged; half the fencing wire had rusted through. A few head of cattle moved along the far ridge, ribs sharp against the dusk. The barn door hung open, roof patched with whatever tin could be salvaged after the big dry of ’55.

Inside, the kitchen held coffee gone bitter and the faint char of stove wood. His brother poured two cups from the pot, set one on the table scarred from years of knives and elbows, took the other to the window. Outside, the wind carried dust against the glass in steady pulses.

They drank. The clock on the wall had stopped years back; no one had bothered to wind it. A moth beat against the screen.

After a time his brother said, “Creek dried up summer before last. Lost the hay crop entirely.”

He nodded.

His brother set his cup down. “North fence is gone in places. Posts rotted out.”

He finished his coffee, placed the cup beside the other. They went out. The dog trailed behind at a distance.

They walked the fence line without words, wire loose between posts like promises their father had never kept. The letters he’d sent home—short, careful lines to their mother so she’d know he was still breathing after Anzio, after the Hürtgen Forest—had stopped mattering long ago. What remained was the ranch, still failing in the same quiet way, and two brothers carrying it forward because no one else would.

Night came down cold. They reached the last post where the wire gave out entirely, nothing but open ground beyond. His brother stopped, looked at the dark ridge, then back at the house lights flickering weak against the black.

He waited.

His brother turned without a word and started back toward the porch. The dog followed. He stood there a moment longer, the wind moving past him like it had moved past everything else for twenty years, then followed too.

The porch light stayed on behind them, small and steady, until the door closed and the night took the rest.

Chapter II — What Still Stands

They worked the fence for three days straight. Posts pulled, holes dug new where rot had taken the old ones. Wire stretched taut, stapled with the same hammer their father had used until the handle wore smooth. No talk beyond what the task required: “Hold here,” “Pass the bar,” “That’s deep enough.” The sun stayed low in late October, light flat and cold. Shadows stretched long by mid-afternoon.

On the fourth morning frost rimmed the water trough. The cattle stood close to it, breath clouding. His brother checked the pump first—primed it, cranked the handle. Sand came up first, then nothing. He let the handle drop.

“Needs a new screen,” he said.

They drove into Medford in the truck. The road followed the same line it always had, dipping through cuts where the CCC had blasted rock in the thirties. Town looked smaller than he remembered—stores with signs faded, one gas station closed, boards over the windows. They bought screen mesh, a length of pipe, fittings. The clerk knew his brother by name, nodded once, said nothing about the stranger.

Back at the ranch they cleared the old screen. Rust flaked into the bucket. Water came slow when they tested it, brown at first, then clearer. The pump groaned like it carried twenty years of complaint.

That night they ate beans from a can heated on the stove. Bread gone stale but edible. The dog waited under the table for scraps that never came.

His brother spoke once, fork paused. “Father kept the books in the top drawer. Never balanced after ’52.”

He looked at the drawer. Wood swollen from years of damp.

“Looked at them once,” his brother said. “Numbers didn’t add up to much.”

He nodded.

They finished eating. Dishes stayed in the sink.

Sleep came in the back room again. The mattress held the same dip. Ceiling cracks still mapped the same rivers. Outside, wind moved through the cottonwoods, branches scraping tin like a slow count.

The limp was worse in the mornings now. He favored the right leg getting out of bed, felt the pull in the left hip where shrapnel had grazed in ’44. Never mentioned it. His brother never asked.

On the sixth day they checked the cattle closer. One cow lagged, udder swollen, eye dull. They separated her in the small pen near the barn. She lowed once, low and tired.

“Can’t save her,” his brother said.

They waited until dusk.

His brother took the rifle from the rack inside the door—the same .30-30 their father had carried. One shot, clean through the skull. The cow dropped without sound beyond the crack. Blood darkened the dust quick.

They dragged her to the gully behind the barn, rolled her in. Coyotes would take the rest by morning. No ceremony. No words.

Back at the house his brother cleaned the rifle barrel with a rag, oiled it, set it back. They drank coffee standing. The lamp threw light across the table in the same circle.

His brother looked at the cup. “She was the last one from the ’43 crop. The year you left.”

He felt the weight settle lower.

“Didn’t know.”

His brother poured more coffee. “Didn’t matter then.”

They stood a moment longer. The clock stayed stopped. A moth beat the screen, or another like it.

Outside, the wind picked up, carrying the smell of pine from the ridge. The porch light flickered once when a branch hit the line, then steadied.

Chapter III — Inheritance

He went to the drawer the next morning while his brother was out checking the lower pasture. The wood stuck when he pulled it open, swollen from years of damp. Inside lay the ledger—leather cover cracked, pages yellowed. Numbers filled the lines in their father’s hand, tight and pressed hard. Losses tallied in red ink from ’48 on. Debts to the bank, to the feed store, to neighbors who never collected.

One page held a letter folded thin.

His mother’s handwriting. Dated ’47.

He writes when he can. Says the trees are thick where he is. France now. I keep the postmarks.

No signature. Just the date.

He folded it back the way he’d found it, closed the ledger, pushed the drawer shut. It caught again, then slid home with a soft knock.

He stood there a moment longer than he needed to. The kitchen was quiet. The clock still stopped. On the back of the chair by the table hung his father’s coat—heavy canvas, collar worn smooth where a hand had rested year after year. He touched the sleeve once, felt the stiffness still in it, then let it be.

His brother came back at noon, dust on his coat. “Calf’s not nursing right. Might lose it too.”

They worked the rest of the day on the pump house—patched the roof, cleared debris from the intake. Hands blistered under gloves worn thin. No complaint spoken. His brother worked the way he always had: steady, deliberate, no wasted motion. The same order every time, like the ground itself expected it.

Evening brought rain. First in months. It started soft, tapping the tin, then harder. Water ran off the roof in sheets, pooling in the yard where the ground had forgotten how to take it.

They stood on the porch watching. The dog stayed inside by the stove.

His brother said, “Might fill the creek a little.”

“Might.”

Rain kept on through the night. He lay awake listening to it drum, to the roof leaking in the same corner it always had. Water dripped into a bucket his brother had set years ago. Steady plink, plink.

Morning came gray. The creek had water in it—thin, muddy, moving slow. Cattle drank from the edge. The calf stood closer to its mother, legs steadier.

They walked the fence again. Wire held where they’d mended it. Posts firm in the wet ground.

His brother stopped at the last post, looked at the open ground beyond. “Could run more head if the water stays.”

He looked too. The ridge was still there, unchanged.

“Could.”

They turned back. Rain had softened the ruts; boots sank deeper. The house waited, door closed against the damp.

Inside, coffee waited. They drank it hot. The dog lay near the stove, wet fur steaming.

His brother set his cup down. “Truck needs oil. Filter’s clogged.”

“I’ll change it.”

His brother nodded once.

Chapter IV — The First Loss

On the sixth day they checked the cattle closer. One cow lagged, udder swollen, eye dull. She stood apart from the others, head low, breathing heavy.

They separated her into the small pen near the barn. She lowed once, tired more than afraid.

“Can’t save her,” his brother said.

They waited until dusk.

His brother took the rifle from the rack inside the door—the same .30-30 their father had carried. He checked the chamber, stepped into the yard, set his feet. The cow lifted her head once when he came near, then stilled.

One shot. Clean through the skull.

She dropped without sound beyond the crack. Blood darkened the dust quick.

They dragged her to the gully behind the barn, rolled her in. Coyotes would take the rest by morning. No marker. No words.

He stood at the edge a moment longer. The gully had deepened since he left, cut wider by rains that came harder some years. The land kept score in its own way.

Back at the house his brother cleaned the rifle barrel with a rag, oiled it, set it back on the rack. They drank coffee standing. The lamp threw light across the table in the same circle as before.

His brother looked at his cup. “She was the last one from the ’43 crop. The year you left.”

He felt the weight settle lower.

“Didn’t know.”

His brother poured more coffee. “Didn’t matter then.”

They stood until the cups were empty. The clock stayed stopped. A moth beat the screen, or another like it.

Outside, the wind picked up, carrying the smell of pine from the ridge. The porch light flickered once when a branch hit the line, then steadied.

Chapter V — Weather

Evening brought rain. First in months. It started soft, tapping the tin, then harder. Water ran off the roof in sheets, pooling in the yard where the ground had forgotten how to take it.

They stood on the porch watching. The dog stayed inside by the stove.

His brother said, “Might fill the creek a little.”

“Might.”

Rain kept on through the night. He lay awake listening to it drum, to the roof leaking in the same corner it always had. Water dripped into a bucket his brother had set years ago. Steady plink, plink.

Morning came gray. The creek had water in it—thin, muddy, moving slow. Cattle drank from the edge. The calf stood closer to its mother, legs steadier.

They moved the herd up the draw where grass still showed green in patches. It wasn’t much, but it was something. The cattle followed slow, heads down, hooves sinking in wet ground. The calf lagged once, then caught up. His brother watched it longer than the rest.

“Could hold them here a while,” he said.

He nodded. They opened the gate, closed it again. No hurry.

By midday the rain had eased. Low sun broke through the clouds, light slanting across the pasture. Steam rose off the cattle backs. The creek ran a little clearer now, water threading around stones that had been dry for months.

They leaned on the fence, breathing hard.

“If it stays,” his brother said, not looking at him.

“If.”

They walked the fence again. Wire held where they’d mended it. Posts firm in the wet ground.

At the last post his brother stopped, looked at the open ground beyond. “Could run more head if the water stays.”

He looked too. The ridge was still there, unchanged.

“Could.”

They turned back. Rain had softened the ruts; boots sank deeper. The house waited, door closed against the damp.

Inside, coffee waited. They drank it hot. The dog lay near the stove, wet fur steaming.

His brother set his cup down. “Truck needs oil. Filter’s clogged.”

“I’ll change it.”

His brother nodded once.

They went out again. The rain had stopped. Sky cleared slow. Sun broke through in patches, light sharp but brief.

He worked under the hood. Wrench turned slow. Oil black as old blood drained into the pan. His brother watched from the porch steps, hands in his pockets.

Neither spoke.

The afternoon stretched. Clouds built again over the ridge. By evening the creek ran slower. Grass dulled back to brown where water had passed through and gone.

They checked the cattle one last time. The calf nursed steady. The rest grazed what they could.

That night the rain came back light, then stopped. The bucket caught less water than before.

The clock stayed stopped.

Outside, the creek murmured low, already losing its voice.

Chapter VI — Winter

Cold came early. Frost stayed on the ground past noon, grass crunching under boots. The creek held water longer than expected, thin stream carving through mud that froze hard at night. Cattle gained a little weight—ribs less sharp, eyes clearer—but not enough to matter.

Snow followed in November. First light, then steady. It piled against the porch rail, muffled the wind. They shoveled paths each morning—yard to barn, barn to corral. Axes rang against the trough, breaking ice so the herd could drink. Steam rose from the holes, then froze again at the edges.

The limp worsened. He favored the right leg more often now, especially on uneven ground. His brother matched pace without comment. One morning a hickory cane leaned against the door when he came in from the barn—his father’s. He took it and used it. Nothing was said.

Hay ran low. They counted bales twice a day, fingers tracing twine. His brother said, “Bank sent a letter last month. Payment due January.”

He waited.

“Said they’d wait if we showed progress. Didn’t say what progress looks like.”

They went back outside.

The bottle came out at night. At first just a little. Then more. Cups filled without toasting. When it emptied, it stayed empty.

December storms came hard. Wind drove snow horizontal. The roof groaned under weight. They climbed up in shifts, shoveling tin slick with ice. Once his boot slid. Pain flared white-hot through the hip. He caught the ridge pole, hung there a moment. His brother reached, pulled him steady. No words. Just hands gripping coat, then release.

Loss followed the weather. One cow went down in the night—old, ribs sharp. Another drowned when meltwater filled the corral knee-deep before dawn. They hauled what they could, meat salvaged quick before rot. The rest they left for coyotes.

Coffee stayed bitter. The clock stayed stopped.

By New Year the yard was rutted deep with ice and mud. The place felt smaller. Quieter. The ridge stayed where it was.

They kept going.

Chapter VII — What Breaks

The thaw came sudden. Late December rain fell heavy on snow, warm enough to undo weeks of cold in a night. Water poured off the roof in sheets, rushed down the draws, filled the yard until it stood ankle-deep by morning. The creek swelled fast, ice cracking loud as gunshots before breaking free.

Mud slid from the ridge, carrying rock and branch. Fence posts leaned where the ground gave way. Wire sagged under the weight.

They found one cow tangled in brush half a mile downstream, body lodged hard against a cottonwood. Another drowned in the corral where meltwater rose too fast. They worked quick, salvaged what they could before rot set in. The rest they left for coyotes.

Hay was gone by New Year.

They sold three head at auction in Medford. Prices were low, buyers fewer than before. The cattle loaded slow, heads down, reluctant in the cold rain. His brother stood at the rail while they were weighed, hands still in his pockets. Didn’t look away when the gate closed.

The money barely covered feed for what remained. The truck needed parts they couldn’t afford.

A neighbor came up the track the next afternoon, same man from down the valley. He stood by the fence, coat collar turned up, watched the thin herd move.

“Got room for a few head,” he said. “Could tide you over.”

His brother shook his head once.

The neighbor waited, then nodded. “Alright.” He didn’t press. Drove off slow, tires carving fresh ruts that filled with water behind him.

Nights grew longer. The bottle stayed empty. They sat by the stove, lamp low, listening to wind test the house.

His brother said once, “Could sell the place. Bank would take it quiet.”

He looked out the window. Snow gone now, ground brown and broken. The ridge bare, unchanged.

“Could.”

They didn’t.

January brought another letter. Foreclosure notice, folded thin. His brother read it standing at the table, set it beside the lamp, said nothing.

Loss kept its pace. A calf born weak in March lasted two days. They buried it shallow in the gully where snow had melted to mud. No marker. Just earth pressed back into place.

The limp worsened. He leaned on the cane more often now, breath shorter after long pulls. His brother noticed. Left water within reach. Took heavier loads without comment.

By spring the mud dried hard. Ruts deepened where wheels had passed. Grass came thin, green only in low spots. The place held, but only just.

They walked the fence line one clear morning. Posts stood where they’d set them. Others leaned. Wire held in places, loose in others.

At the last post his brother stopped. Looked at open ground beyond. Wind moved sage low.

He waited.

His brother turned without a word and started back toward the house.

He followed.

Chapter VIII — The Leaving

He loaded the truck in the morning. Not much. Coat, cane, a small sack of coffee. Things he could carry without looking back.

His brother watched from the porch, hands in his pockets. The dog sat at the steps, head tilted.

He started the engine. Let it idle. The sound filled the yard, then settled.

He sat with the door open, one boot on the ground. Looked at the house—leaning as it always had. The porch light off. The window dark.

His brother stepped down once, crossed the yard. Handed him a small bundle wrapped in cloth. Jerky. Coffee grounds. He took it.

“Road’s dry,” his brother said.

He nodded.

His brother stepped back. The dog whined low.

He closed the door. Put the truck in gear. Tires crunched gravel. Dust rose slow behind him.

At the cattle guard he stopped. Looked back once. The porch was empty now. The ridge stood where it always had.

He eased forward. The track stretched ahead, same ruts, same dust.

The truck disappeared over the rise.

Chapter IX — What Remains

The dust from the truck settled slow behind the rise. The sound of the engine faded, swallowed by the valley.

His brother stood on the porch a while longer. The dog waited at his heel. When nothing else came, he turned back inside.

Coffee still sat warm on the stove. Two cups on the table—one half full, one empty. He poured what remained into the empty cup and drank it standing. The stove ticked as it cooled. The clock stayed stopped.

Outside frost rimmed the trough again. He broke the ice with the axe, same rhythm as always. The cattle drank. Breath clouded white. Fewer head than before, but enough.

He walked the fence line alone. Posts held where they’d set them. Wire sagged in places, taut in others. The ridge stood black against the pale morning.

At the last post he stopped. Rested a hand on the wire. Felt the cold metal bite through the glove. Wind moved low through the sage.

He stayed there a moment longer than he needed to.

Then he turned and started back. Pace slow. The dog followed.

Inside, the house held its quiet. He set the cups in the sink. Banked the stove. Hung the axe on its nail. The lamp stayed off.

Outside, the cattle shifted along the fence. Hooves pressed the ground deeper into the ruts.

He went on with the work.