Chapter One — The Weight of Snow

Late February came in layers.

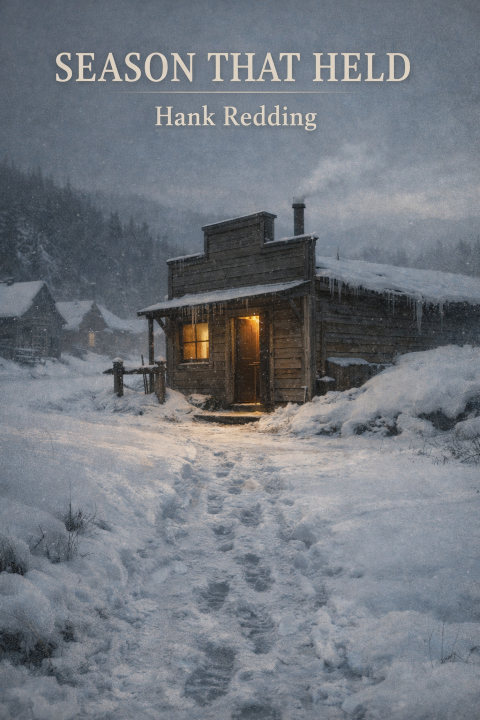

It had been snowing for three days with no sign of stopping, not hard the way men talked about blizzards after they’d survived one, but steady—quiet flakes that didn’t look like much until you stepped outside and realized the world had risen up around you. Bitter Creek had a way of getting buried without ever being announced.

Cal Harlan stood in the doorway of The Last Drift with his hands in his coat pockets and watched the street disappear.

There wasn’t much of a street left. Just a pale, narrowed cut between cabins and the black shapes of outbuildings, drifted in on both sides until it looked like a trench someone had stopped digging. The snow had filled in the wagon ruts and softened the corners of things that used to feel permanent. Fence posts leaned with white caps. The hitching rail was half gone. The mine office down the way looked smaller each day, as if the winter was taking it back board by board.

The wind never quit. It didn’t roar. It worried the town the way a hand worries a worn coin—over and over until every edge feels different.

A man could hear Bitter Creek working under it: the creak of timber, the faint tick of stove pipes cooling, the distant thump that might’ve been a roof shedding weight or a mule shifting in its stall. Even when the camp looked still, it wasn’t. Nothing stayed still in a place like this. It only held.

Behind him, the saloon kept its own weather.

Kerosene lamps threw a soft yellow over the bar and the tables, turning every bottle into amber. The stove in the corner pulsed with heat, popping now and then like it had opinions. The air smelled of wet wool, cheap whiskey, and smoke that had settled into the boards years ago and never found a reason to leave.

The miners were thin on the floor tonight. Storms made men either thirsty or careful, and right now more of them were choosing careful. The few that had come in sat hunched over their drinks like they were guarding them, shoulders raised against a cold that followed them indoors. Talk stayed low. Cards slapped now and then at the back table, not loud enough to feel like fun.

Cal didn’t mind quiet. He’d spent years on freight runs where the only voice that mattered was the one inside your own head, the one that reminded you to watch your footing on ice and not trust a bridge just because someone had told you it would hold. Quiet kept a man honest. Loud things had a way of making promises.

He turned from the doorway and set the latch with care, more habit than necessity. The storm could’ve taken the door off its hinges if it wanted. Tonight it seemed content to lean against the building and see what gave.

“Last call,” he said, not as a command, just a fact.

No one argued. A couple of men drained what was left in their glasses and stood, moving stiffly the way men did after hours in wet boots. One of them nodded at Cal as if nodding could pay a tab. Cal let it count. He’d been hungry enough in his life to know the difference between a man who planned to make it right and one who never would.

Lila Voss was wiping down the nearest table with a rag that had already seen too much of the world. She worked in long sleeves the way she always did, cuffs buttoned, hair pinned back so tight it made her face look more tired than it was. The lamp light caught the pale skin at her throat when she leaned forward, and Cal found himself looking away, not out of embarrassment but out of respect. Some parts of a person felt like private property, even when they didn’t belong to anyone but themselves.

She moved with the careful efficiency of someone who had learned what breaks if you hurry.

When the last miner pushed out into the snow, the room fell even quieter. The stove and the lamps and the occasional creak of the building did most of the talking. Lila stacked glasses without clinking them. Cal counted out the till without making noise. Between them there was a kind of understanding that didn’t need naming.

Lila had started coming in afternoons a few weeks earlier, when Cal’s usual helper had gotten sick with a cough that didn’t seem interested in leaving. She hadn’t asked for work with any drama. Just stood in the doorway one day, snow on her shoulders, and said she could wipe tables and carry trays if he needed hands. Her voice had been steady, but she kept her eyes on the floorboards like she didn’t trust herself to look a man in the face without giving something away.

Cal hadn’t asked why she needed it. He’d seen enough in a camp like this to know that most explanations were either too heavy to carry or too dishonest to bother with. He’d handed her a rag and told her where the clean glasses sat.

She’d shown up the next day, and the next. Always on time. Always quiet. Never asking for more than what he’d offered.

Now she wrung out the rag at the wash basin and hung it neatly, as if a neat rag could keep the world from unraveling.

“That’s it,” Cal said when she reached for another table.

Lila paused. “There’s still—”

“It’ll be there tomorrow,” he said.

Her hand hovered over the tabletop for a moment, fingers spread flat against the wood as if feeling for heat that wasn’t there. Then she nodded once and set the cloth down.

She pulled on her coat—thin wool, patched at the elbows—and tied her scarf with the same small precision she used for everything. Cal watched her without trying to. The way she moved always made him think of a person walking across lake ice, choosing each step like it might be the one that proved too much.

At the door she hesitated.

Not long. Just the brief stop of someone measuring what waited outside. The storm had thickened since sundown. The street was a moving wall of white, the wind turning snow into needles that found every seam.

Her cabin sat up the gulch, past the last lean shacks and the tree line that took the brunt of the wind. Half a mile in good weather. Longer in this.

Cal took his hat from the peg and settled it on his head. “I can walk you partway.”

He said it like he might’ve offered to carry a sack of flour. Practical. Nothing in his voice that tried to turn it into something else.

Lila’s eyes flicked to him, and for a moment he saw the quick calculation there—what it would cost, what it would mean, what it would invite. Then the expression smoothed back into the polite face she wore like an apron.

“I’ll be all right,” she said.

Cal nodded. He didn’t argue. Arguing with a woman about what she could handle felt too much like telling her she couldn’t.

But she didn’t open the door.

Her gloved hand rested on the latch, and she stared into the lamp-lit glass as if she could see through it to the path beyond.

The silence stretched—not awkward, just present. Like the winter itself, waiting for someone to move.

“You got boots that’ll hold?” Cal asked.

She glanced down at her feet. “They’re fine.”

Cal looked at them anyway. The leather was worn, the soles thin at the edges, but they were laced tight. Everything about her was tight.

He reached under the bar and pulled out a small tin. He set it on the counter between them, not sliding it, not pushing. Just placing it there.

“Coffee,” he said. “If you want it. Grounds are good.”

Lila stared at the tin. Her mouth tightened, almost like she was swallowing something. Then she nodded once, quick, the way people nod when they’re trying not to show gratitude because gratitude can be mistaken for weakness.

“I can pay you,” she said.

“Don’t,” Cal replied.

He watched her take the tin and tuck it into her coat like it was something fragile. She didn’t thank him out loud. Instead she met his eyes, briefly—just long enough for something to pass between them that wasn’t comfort and wasn’t fear, but lived close to both.

Then she opened the door.

Cold rushed in, sharp and immediate, putting out half the warmth like a hand slapped over a lamp. Snow blew across the threshold and scattered in on the floorboards. Lila stepped into it without flinching, but Cal saw the way her shoulders rose, instinctive, bracing.

She turned once, as if reconsidering. Not about the walk. About something older.

Cal didn’t fill the space. He knew better.

After a moment she pulled the door shut behind her.

The latch clicked.

The sound landed heavy in the empty room.

Cal stood there a beat longer than he needed to, listening to the wind take back the last trace of her footsteps outside. Then he turned, banked the stove, and started putting the saloon to sleep.

Up in the loft room above the bar, his leg ached the way it always did when the cold settled in deep. He sat on the edge of his bed and rubbed the old scar through his trousers, not because it helped but because it reminded him where the pain lived. Better to know where something was than to have it move around on you.

He thought of the way Lila had paused at the door.

He’d seen men hesitate before. Men deciding whether to brave a storm or wait it out and risk going hungry. Men deciding whether to step into a fight or let it pass. But Lila’s hesitation hadn’t looked like a calculation of weather. It had looked like a person weighing what waited at the other end of the walk.

Cal lay back and stared at the ceiling boards, where shadows from the stove light made slow moving shapes.

He told himself not to guess at things he didn’t know. Bitter Creek was full of stories, and most of them were lies people told so they didn’t have to admit they were afraid.

Still, the camp had its truths, too. Quiet ones. The kind you didn’t hear unless you listened for what people didn’t say.

Outside, the wind pressed its shoulder against the town again.

Snow kept falling, covering the street until it looked untouched.

Like no one had ever tried to leave.

Chapter Two — Patterns

Snow didn’t stop after that night. It only learned the town better.

By morning the drift outside The Last Drift had risen enough that Cal had to shoulder the door twice before it gave. Cold spilled in, clean and sharp, carrying the sound of the creek somewhere under its ice. Bitter Creek ran all winter, even when the town pretended otherwise. It didn’t hurry. It just kept moving where it could.

Cal stamped his boots clear and set the lamps one by one. Light arrived slowly, like it was considering whether the effort was worth it. He liked the place better before the miners came in—when the bar was bare, the tables wiped clean, and everything sat exactly where it belonged. Order before weather and men had their say.

By noon the room had warmed enough to take the edge off a man’s hands. The first miners came in with snow still clinging to their coats, faces red and cracked from the wind. They drank without ceremony. Talk stayed thin. Everyone was watching the storm, measuring it against what little they had left.

Lila arrived midafternoon.

Cal didn’t hear the door open. He noticed her because the room changed. Not quieter—just altered, like something had been shifted an inch and now everything sat a little off.

She brushed snow from her sleeves and hung her coat on the peg by the door, careful to shake it outside first. Her movements were slower today. Deliberate. When she reached up to take a stack of clean glasses from the shelf, she did it in two motions instead of one—testing the stretch before committing to it.

Cal said nothing. He poured a whiskey for a miner at the bar and slid it over.

Lila wiped tables. The rag dragged faint lines through last night’s water rings. She leaned into her work like she always did, head down, hair pinned tight. But when she turned, Cal caught a glimpse of shadow along her jawline, just under the skin. Not dark enough to announce itself. Dark enough to notice if you were looking.

He wasn’t sure when he’d started looking.

A man laughed too loud at the back table. Just a bark of sound, gone as soon as it came. Lila flinched anyway, barely—a hitch in her shoulder, a pause half a second long before she kept moving.

Cal felt something settle in his chest, familiar and unwelcome.

He’d seen fear before. Men carried it openly in a place like this—fear of bad ore, fear of cave-ins, fear of waking up one morning and finding the mine closed for good. That kind of fear walked loud. It complained. It drank.

This was different. This was the kind that learned how to stay small.

Later, when the room filled enough that Cal needed help behind the bar, Lila stepped in without being asked. She poured carefully, watching the men’s hands more than their faces. When one reached across the bar too fast, she shifted back a step, smooth as breath. The man didn’t notice. Cal did.

“Thanks,” Cal said when she passed him a bottle.

She nodded, eyes on the counter.

A miner near the door grumbled about a bad shift. He talked about rock that looked promising and came up empty, about a foreman who counted costs like he was measuring men. His voice sharpened as he spoke, each sentence cutting a little deeper than the last.

Lila’s hand tightened on the glass she was drying.

The glass slipped.

It didn’t fall far—just enough. It hit the edge of the bar and shattered, sharp and sudden. The sound cracked through the room like a rifle shot.

Every head turned.

Lila froze.

Her breath caught so hard Cal heard it from where he stood. She stared at the broken pieces at her feet like they’d done something unforgivable.

“I’m sorry,” she said. Then again, softer. “I’m sorry.”

Cal moved before anyone else could speak.

“Happens,” he said, already crouching. He took the broom from behind the bar and swept the shards into a neat pile, careful not to rush it. “That one was waiting its turn.”

A couple of miners chuckled, the sound uneasy but relieved. One of them said something about clumsy hands. Cal shot him a look—not sharp, just present—and the man found his drink more interesting than conversation.

Lila knelt, reaching for a piece Cal had missed.

“Don’t,” he said.

She stopped instantly, hand hovering inches from the glass.

“I’ll get it,” he added, quieter.

She drew back, folding her hands into her sleeves like she was keeping them out of trouble. Her face had gone pale under the lamplight, and for a moment Cal wondered if she might be sick.

When the floor was clear, he set the broom aside and straightened.

“All right,” he said. “No harm done.”

Lila nodded too fast. “I’ll fetch another.”

“You will,” Cal said. “When you’re ready.”

She stood there a second longer than necessary, like she was waiting for something else to come. When it didn’t, she let out a breath she hadn’t known she was holding and moved away.

The room settled back into itself. Cards slapped. A man cursed softly at his luck. The stove popped.

But the crack from the breaking glass lingered, hanging where it had landed.

After closing, Lila stayed without being asked. She stacked chairs and wiped the bar down slow, careful around the spot where the glass had broken earlier, like it might still be dangerous.

Cal counted the till. When he was done, he pushed a few coins toward her side of the bar.

“For the extra time,” he said.

She frowned at the money. “I broke a glass.”

“So?” Cal replied.

She hesitated, then took the coins and tucked them away, eyes down.

As she reached for her coat, Cal noticed the way she favored one side, the way she adjusted her sleeve before pulling it on. The movement was small, but practiced. Like she’d learned where it hurt and how not to show it.

“Cold’s set in deep,” he said.

She nodded. “It always does.”

At the door she paused again. Not as long as the night before, but long enough to feel like habit.

“You all right walking?” Cal asked.

“Yes,” she said. The answer came quick. Too quick.

Cal watched her go, listened to the door shut behind her, and felt the quiet settle heavy again.

He stayed where he was for a long moment, hands resting on the bar, thinking of patterns. Of how some things repeated not because they wanted to, but because no one stopped them.

Outside, snow slid off the roof in a soft rush, filling in the path she’d just taken.

The town held its breath.

And somewhere up the gulch, a cabin waited, dark against the white.

Chapter Three — Warmth Without Questions

The storm settled into itself the way some things did when they realized no one was going to stop them.

By the end of the week, Bitter Creek moved differently. Men took fewer chances. The path between buildings narrowed to what had been walked often enough to hold. Anything outside those lines disappeared quickly, filled in by white until it looked like it had never been meant for use.

The Last Drift stayed open late, not because business was good but because there were fewer places to go. Cabins went dark early now. Wood was precious. Light was rationed. The saloon, with its lamps and its stove and its stubborn refusal to close, became a kind of commons—no one said it, but everyone felt it.

Cal kept the fire fed and the lamps trimmed. He didn’t rush men out anymore. He let them sit with their drinks until they were ready to face the cold again, or until the cold came looking for them.

Lila worked most nights.

She didn’t say much, and no one pressed her to. The miners treated her with a careful politeness that felt practiced, as if the camp had decided without discussion that she wasn’t to be pulled into their noise. When one man tried, leaning too far across the bar with a grin that asked for more than it deserved, Cal cleared his throat—not loud, just enough—and the man found his stool suddenly uncomfortable.

Lila never acknowledged it. She poured drinks. She wiped tables. She stayed where she could see the door.

Cal noticed she’d begun to linger after her shift ended. Not in a way that drew attention—just small delays. One more table wiped. One more chair straightened. She never sat. She just stayed where it was warm.

One night, as the lamps burned low and the last card game broke up, Cal poured himself a drink he didn’t need and set it aside untouched.

“You can sit,” he said, nodding toward the stool nearest the stove.

Lila shook her head. “I should get going.”

“The wind’s picked up,” Cal said. “Give it a minute.”

She hesitated, the way she always did, weighing something that wasn’t weather. Then she took the stool, perching on the edge like she planned to stand any second.

The heat had put color back into her face. The shadows under her eyes hadn’t gone anywhere, but they’d softened, like they were waiting.

They sat in silence. Not the empty kind. The kind that had room in it.

Outside, something banged loose and struck the side of the building. Lila flinched, sharp and sudden, then stilled herself when she realized what it was.

Cal said nothing. He reached for the poker and nudged the coals into a better arrangement. The stove responded with a low, satisfied sound.

“Feels louder at night,” Lila said, surprising them both.

“The wind?” Cal asked.

She nodded. “Everything.”

Cal considered that. “Nothing else to drown it out.”

She looked at him then, really looked, like she was checking to see if he meant something by it. When she saw that he didn’t—at least not in a way that required answering—she relaxed back into the stool.

“My mother used to say winter was honest,” she said. “That it showed you what mattered.”

Cal didn’t ask where her mother was now. He’d learned the weight of questions like that.

“What did she think mattered?” he asked instead.

Lila shrugged, a small movement. “Staying.”

Cal let that sit.

Outside, the wind leaned in again, testing the walls. The saloon answered with creaks and groans, old complaints from old wood.

After a while, Lila stood. She reached for her coat, hesitated, then let her hand fall away.

“Would you—” She stopped, breath caught. “Could I warm up a little longer?”

Cal nodded. “As long as you need.”

She took the stool again, closer to the stove this time. She held her hands out to the heat, palms open like she was remembering how to receive something.

Cal watched the fire.

When she finally left, the snow had eased enough that the street showed through in places, gray beneath the white. Cal waited until the door closed behind her before blowing out the lamps.

He didn’t follow her.

He didn’t need to.

From the doorway, he watched until the storm took her shape back into itself.

Some warmth, he knew, didn’t come from being held.

It came from being allowed to stay.

Chapter Four — The Door Left Open

School let out early the day the temperature dropped enough to make breath crack.

Bitter Creek didn’t have much of a school—just a low building near the creek with two rooms and a stove that worked when it felt like it. Still, it gave children somewhere to go besides the street, and that counted for something. When the storm worsened around midday, parents fetched their young ones early, pulling them along the packed paths with gloved hands and promises of soup.

One miner came into The Last Drift with his daughter wrapped in a coat too big for her, sleeves hanging past her fingers. She couldn’t have been more than nine. Her cheeks were raw with cold, her hair escaping its ribbon in dark wisps that clung to her face.

Cal nodded to the man. “Cold enough to steal teeth.”

The miner grunted agreement and stamped snow from his boots. “She wanted somewhere warm.”

“That’s what this place does,” Cal said.

The girl looked around with open curiosity, eyes wide at the lamps and bottles and the stove breathing heat into the room. She hovered near her father at first, then drifted a few steps away when she realized no one was watching her too closely.

Lila noticed immediately.

She had been wiping the far table, her back to the door. She turned, saw the girl, and something in her posture changed—not fear, not exactly. Recognition. Like seeing a shape you hadn’t realized you were waiting for.

The girl wandered toward the stove, hands stretched out, palms up. She smiled without meaning to, the way children did when warmth found them.

Near the back door, a man sat alone.

Cal hadn’t noticed him come in. That happened sometimes—transients slipping through when weather pushed them off the trail. He was bundled heavy, coat frayed, beard rimed with frost that hadn’t quite melted yet. He held his drink loosely, like it was optional.

The girl edged closer, curious.

The man reached into his pocket.

Cal felt it then—not alarm, not certainty. Just a tightening, the way air changed before snow fell harder.

The man produced a piece of hard candy, dull and amber-colored. He held it out, palm open.

“Cold out there,” he said. His voice was mild. Friendly enough.

The girl hesitated. Looked back toward her father, who was deep in conversation with another miner. No one was watching.

Lila crossed the room in three steps.

She didn’t raise her voice. She didn’t touch the man.

She took the girl’s hand.

“Your father’s waiting,” she said, already turning her away.

The girl blinked, confused, but went willingly. Lila guided her back to the bar and set her gently beside her father, one hand firm on the girl’s shoulder until the man looked down and noticed.

The transient withdrew his hand. His expression didn’t change.

Cal met his eyes from behind the bar.

Nothing was said.

The moment passed the way moments did when they weren’t fed—thin, unsatisfying, gone.

But Lila stood where she’d left the girl, shoulders tight, breath shallow. She didn’t look back at the door. She didn’t look at Cal.

She went to the wash basin and scrubbed her hands until the skin reddened.

That night, after the lamps were low and the last miner had gone, Lila stayed.

She stacked chairs without being asked. Straightened what was already straight. Her movements were quick now, restless, like she was outrunning something that kept pace no matter how fast she went.

Cal wiped the bar and waited.

When she finally spoke, it came out sideways.

“I don’t like open doors,” she said.

Cal looked at her, careful. “Drafts’ll do that.”

She nodded too quickly. “They make promises.”

The words hung there, heavier than they’d meant to be.

She set a chair down harder than necessary and stopped herself, fingers tightening on the back.

“When I was little,” she said, and then paused, as if surprised by the sound of her own voice continuing. “There was a house near ours. Just down the road. A place you passed every day without thinking about it.”

Cal stayed still.

“The door was always open,” she said. “Even in winter.”

She swallowed.

“They said it was because the stove smoked. Because someone was always coming or going. Because they were friendly.”

Her hands had gone white on the chair.

“I thought it meant something,” she said. “I thought it meant you could step inside and not be cold anymore.”

She stopped.

Silence filled the space where more might have gone. Cal didn’t reach for it. He knew better than to pull at a thing someone had barely set down.

“That girl today,” Lila said after a moment. “She didn’t do anything wrong.”

“No,” Cal said.

“She didn’t know.”

“No,” he said again.

Lila nodded, like she’d proven something to herself. She picked up the last chair and set it in place, movements steadier now, like the telling had taken something out of her and left room behind.

“I should go,” she said.

Cal didn’t argue.

At the door, she paused—as she always did—but this time she spoke before he could.

“Thank you,” she said, not for the night, not for the work. For something older.

Cal nodded. “Anytime.”

After she left, Cal stood alone in the saloon and stared at the back door.

He thought of the way some people learned early what warmth could cost. How they learned to confuse safety with invitation. How long it took to unlearn.

Outside, the wind closed the door the rest of the way.

Snow pressed up against it until there was no line left between inside and out.

Just the knowledge of which side you stood on.

Chapter Five — Watching Without Touching

By early March, the paths through Bitter Creek had worn themselves thin.

There were places where the snow had been packed hard enough to shine, polished by boots and hooves until it looked like ice that had learned to behave. Step outside those lines and you sank to your knees, sometimes deeper. The town had decided, without discussion, where movement was allowed.

Cal learned the routes the way he learned men—by noticing what repeated.

He noticed which lamps went dark first. Which cabins burned late. Which doors opened easily and which resisted, even in daylight. He noticed that Jed Voss came into the saloon less often now, and when he did, he didn’t stay long. He drank standing up. He watched the room like it owed him something.

He noticed that on those nights, Lila worked closer to the bar.

Cal didn’t ask questions. He didn’t offer advice. He did the only thing he believed in—he made sure the room stayed predictable.

When Jed came in, Cal didn’t change his posture. He didn’t lower his voice or raise it. He didn’t hurry or slow. He poured the drink the same way he poured every drink. He kept his eyes level.

Jed noticed.

Men like that always did.

Once, when the saloon was full enough to make noise feel like cover, Jed let his hand linger too long on the bar, fingers tapping once, twice, like punctuation.

“Long walk home tonight,” he said, not looking at anyone in particular.

Lila stiffened.

Cal wiped the counter where the man’s hand had been.

“Storm’s easing,” Cal said. “Tracks’ll hold.”

Jed smiled, but it didn’t reach his eyes. He drained his glass and left without another word.

After that, Cal started walking the path behind Lila on nights she stayed late.

Not beside her. Never beside her.

He kept far enough back that she wouldn’t feel followed, close enough that the distance meant something. If she stopped, he stopped. If she sped up, he let her. If she turned, he’d step into sight so she wouldn’t have to guess.

She never acknowledged it.

The snow took care of that.

Sometimes he saw the glow from her cabin before she reached it. Sometimes the place was dark, the chimney cold. On those nights, Cal stayed longer at the edge of the trees, watching until the door closed behind her and the latch set.

He didn’t know what waited inside. He didn’t pretend to.

One evening, when the cold settled so deep it made the wood ache, Lila didn’t come in.

Cal noticed by the way the room failed to shift.

The saloon filled and emptied. The stove burned down and was fed again. Men drank and talked and complained the way they always did. But the door stayed quiet.

Near midnight, Cal closed early.

He walked the path himself, boots breaking the crust where the day’s warmth had tried and failed to make peace with the night. Snow reached his calves in places. The wind had scoured others clean.

Lila’s cabin sat with its door shut, smoke curling thin from the chimney. Light showed in one window.

Cal stopped short of the clearing.

He didn’t go closer. He didn’t call out.

From where he stood, he could hear voices. Jed’s voice, low and controlled. Lila’s, quieter. The words didn’t carry. The tone did.

There was a pause. Long enough to feel.

Then the light went out.

Cal stood there until the cold worked its way through his coat and into the old injury in his leg, a dull reminder that some things never healed clean. He turned back toward town without seeing the door open again.

The next night, Lila returned to the saloon.

Her sleeves were buttoned higher than usual. Her movements were careful, precise to the point of strain. When she reached for a bottle on the top shelf, she used both hands.

Cal said nothing.

Later, as the lamps burned low and the miners drifted out one by one, Cal poured two cups of coffee and set one near the stove.

Lila eyed it like it might ask something of her.

“You don’t have to,” she said.

“I know,” Cal replied.

She took it anyway.

They stood on opposite sides of the stove, heat between them, not touching. The silence stretched and held.

“You ever think about leaving?” Lila asked suddenly.

Cal didn’t answer right away. He thought of freight roads that went on forever. Of camps that vanished behind him. Of a sister buried where the ground never quite thawed.

“Sometimes,” he said.

She nodded, satisfied with that.

“Winter makes it harder,” she said.

“It also makes things clear,” Cal replied.

She looked at him then, really looked, like she was seeing not what he offered but what he refused to claim.

For the first time since he’d known her, she didn’t look away first.

Outside, the wind shifted direction, carrying the faint sound of Bitter Creek working its way under ice and stone.

Cal finished his coffee and set the cup down.

“When you’re ready to go,” he said, “I’ll lock up.”

She nodded.

Neither of them moved right away.

Some watching, Cal had learned, wasn’t about seeing.

It was about staying where you were until the other person decided whether to step forward—or not.

Chapter Six — When Silence Stops Working

Jed came in just after dark.

The lamps were already lit, the stove fed enough to take the edge off the cold without inviting anyone to linger too long. A handful of miners sat scattered through the room, drinks close, shoulders hunched. Cards moved at the back table with quiet efficiency. The storm had eased, but no one trusted it.

The door opened hard enough to knock snow loose from the frame.

Jed didn’t stamp his boots. He didn’t shake the cold from his coat. He stepped inside like the weather belonged to him.

The room noticed.

Conversation thinned. A card slapped late. Someone cleared his throat and found a reason to look down at his drink.

Lila was at the far table, wiping it clean for the third time. She didn’t turn when the door opened, but Cal saw the shift in her shoulders, the way her spine straightened like it had been pulled by a string.

Jed crossed the room without hurrying.

He stopped at the bar, close enough that Cal could smell the cold on him, sharp and clean and edged with whiskey from somewhere else.

“Evening,” Jed said.

Cal nodded. “Jed.”

“What’s good?” Jed asked, eyes sliding past Cal to where Lila stood.

Cal didn’t follow the look. “Same as always.”

Jed smiled thinly. “That’ll do.”

Cal poured the drink and set it down. He didn’t rush. He didn’t delay. He didn’t ask for coin until Jed reached for his pocket on his own.

Jed took a swallow and let it sit in his mouth a moment too long.

“Lila,” he said then, voice carrying just enough. “You about ready?”

The word ready landed wrong. Too much weight in it. Too much expectation.

Lila turned.

“Yes,” she said.

She didn’t sound afraid. That was the trouble. She sounded practiced.

Jed’s eyes flicked to her sleeves, buttoned tight despite the heat. To the way she held her hands, fingers tucked in like they might misbehave.

“You been busy?” he asked.

“Yes.”

Jed nodded, as if confirming something he’d already decided.

Cal wiped the counter where nothing had spilled.

“Storm’s moving back in,” he said. “Might be worth waiting.”

Jed looked at him then. Really looked.

“That your concern?” Jed asked.

Cal met his eyes.

“Everyone’s,” he said.

The word hung there, plain and unadorned.

Jed laughed softly. Not humor. Dismissal.

“She’s my wife,” he said.

Lila didn’t move.

Cal didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t lean forward. He didn’t step back.

“I know,” he said.

Something shifted then—not loud, not visible. Just the subtle realignment that happened when two men realized the space between them had meaning.

Jed set his glass down with care.

“You always got a lot to say?” he asked.

“No,” Cal replied.

A miner near the stove stood abruptly, muttered something about air, and pushed out into the night. Another followed, slower, unwilling to be last.

The room thinned itself.

Jed took one step closer to the bar. Not a threat. A test.

Lila’s breath caught.

Cal stayed where he was.

“Drink up,” Cal said. “Road’s long.”

Jed held his gaze another second, then drained the glass.

“We’ll talk later,” he said, not to Cal.

Cal watched him turn. Watched Lila take her coat from the peg, hands steady only because she forced them to be. Watched them walk to the door together, close but not touching.

The door shut behind them.

The latch clicked.

The sound echoed longer than it should have.

Cal stood alone behind the bar, hands flat on the wood, feeling the way silence rushed back in to fill the space men had vacated.

He didn’t follow.

Not yet.

Outside, the wind rose again, quick and sharp, like it had been waiting for permission.

Snow began to fall, light at first, then steadier, erasing the tracks almost as soon as they were made.

Cal reached for the bottle, poured a drink, and set it aside untouched.

He knew the shape of this moment. He’d seen it before, in other places, under other names.

There were times when silence kept the peace.

And times when it only kept the count.

Chapter Seven — The Storm That Breaks Things

The lanterns went out just before dawn.

Not all at once. One guttered near the mine office, flame stretching thin before surrendering. Another followed down the street, then another, until Bitter Creek woke to a gray light that belonged to no hour anyone trusted.

The storm had returned in earnest sometime after midnight. Snow fell heavy now, pressed flat by wind that came down the gulch with purpose. Roofs sagged under it. Doors froze shut. The creek’s voice disappeared entirely, buried under ice and drift.

Cal woke to the sound of something giving way—not crashing, just a long, tired groan as a beam settled where it hadn’t planned to. He dressed slow, favoring his bad leg, and lit the stove with practiced hands.

By the time the saloon warmed enough to matter, the town was already struggling.

Men came in wrapped in whatever they owned, faces drawn tight. The mine was shut—no light, no safe way down. A cave-in had taken part of the lower shaft with it, and though no one had been hurt, pay was gone with it. Weeks of work turned into cold air and bad luck.

Tempers frayed quietly.

Cal poured coffee instead of whiskey at first. No one complained. They sat with their cups cradled like anchors, eyes on the stove or the door or nothing at all.

Lila didn’t come in.

By noon, Cal had stopped expecting her.

He didn’t say it out loud. He just found himself listening harder whenever the door shifted under the wind.

The storm worsened as the day dragged on. Snow crept up the sides of buildings like it meant to stay. The path up the gulch disappeared entirely, swallowed clean.

Near dusk, a man staggered in with news that Jed Voss had been seen earlier, heading home in a foul mood, cursing the mine and everything attached to it.

Cal felt the old tightening settle in his chest.

He closed early.

No one argued. No one asked why.

The walk up the gulch was harder than it had been any night before. Snow filled Cal’s boots and froze there. The wind cut at his face until his eyes watered. He leaned into it, teeth set, knowing better than to fight what couldn’t be pushed back.

Lila’s cabin came into view slowly, like it was emerging from somewhere else entirely.

The door stood open.

Not wide. Just enough.

Snow had drifted inside, filling the threshold, softening the floorboards into pale shapes. The lantern inside had gone dark. The chimney smoked weakly, like it had been neglected.

Cal stopped short.

He didn’t call out.

He stepped inside.

The cold had teeth in the room. Whatever warmth had been there earlier had fled. Lila sat on the floor near the stove, coat still on, shawl pulled tight around her shoulders. One cheek had begun to darken, the skin swollen just enough to catch the eye.

She looked up when she heard him.

Relief crossed her face before she could stop it. Then something else—fear, maybe, or shame at being seen this way.

“He’ll be back,” she said. Not as a warning. As a fact.

Cal nodded. He took in the room without staring. The overturned chair. The untouched pot on the stove, long since gone cold. The way the door hadn’t been closed all the way.

He knelt beside her, not touching.

“You hurt?” he asked.

She shook her head once. Then again, smaller. “Nothing I can’t handle.”

Cal didn’t argue.

“He said it was my fault,” she said. “That supper wasn’t ready. That I knew what kind of day he’d had.”

Cal felt something steady itself inside him.

“You don’t have to stay here tonight,” he said.

She looked at him sharply. “I can’t just—”

“You can,” Cal said. “For tonight.”

The wind slammed the door open wider, snow blowing in hard.

Footsteps sounded outside.

Jed’s voice carried, low and sharp.

“This ain’t your business.”

Cal stood.

He turned so he was between Jed and Lila without making a show of it.

“She’s worth more than being made to feel small every day,” Cal said.

Jed laughed. Short. Unpleasant.

“Is that what you think this is?” Jed asked.

Cal didn’t answer.

Jed looked past him, at Lila on the floor, at the open door, at the storm pressing in like it wanted a say.

Something flickered across his face—anger, calculation, pride. Then he grabbed his coat.

“I’ll sort it later,” he said, already turning.

The door slammed shut behind him.

The storm took him back.

Cal waited until the sound of his steps disappeared entirely before turning back.

Lila was shaking now, small tremors she couldn’t stop.

Cal reached out then, just enough to help her stand.

“Come on,” he said. “Let’s get you warm.”

She hesitated only a second.

Outside, the snow closed in behind them, erasing the path as fast as they made it.

The town lay dark ahead, lamps gone, windows dim.

But The Last Drift still burned.

And for the first time in a long while, Lila walked without flinching when a door banged shut behind her.

Chapter Eight — Borrowed Time

The room above the saloon had been meant for storage.

Old ledgers sat in a crate beneath the window, their covers warped from years of steam and cold. A narrow bed hugged one wall, the mattress thin but clean. A small table held a lamp and nothing else. It wasn’t comfort, exactly—but it was solid, and it was warm.

Cal lit the lamp and set it on the table. The flame steadied.

“You can stay here,” he said. “As long as you need.”

Lila stood just inside the doorway, hands folded into her sleeves, eyes moving over the room as if cataloging it for danger. She didn’t sit. She didn’t set her bundle down.

“Jed—” she began.

“Isn’t here,” Cal said. “And won’t be tonight.”

She swallowed. “He’ll come back.”

“Maybe,” Cal said. “Not up here.”

She studied his face for the catch that never came. The offer had edges she couldn’t see, and that made her wary.

“There’s no debt,” Cal said, quietly. “No questions. No one needs to know.”

Her shoulders sagged then, just a fraction. The smallest release.

“I don’t have much,” she said. “I didn’t plan—”

“You brought what mattered,” Cal said, nodding to the small box tucked under her arm. A keepsake, worn smooth at the corners. He didn’t ask what was inside.

She set it on the table and touched it once, like she was checking that it was still real.

“I’ll get you some soup,” Cal said. “And fresh water.”

She nodded.

When he returned, she was sitting on the edge of the bed, boots still on, hands in her lap. She took the bowl carefully, like it might spill more than heat.

“Thank you,” she said, and this time the words held.

They ate in silence. The storm battered the roof, a low, relentless sound. Snow slid off in sheets now and then, thumping against the walls.

Cal leaned against the doorframe, making himself small.

“You don’t have to decide anything,” he said. “Not tonight. Not tomorrow.”

Lila stared into the soup. “If I leave,” she said slowly, “it has to be for good.”

Cal nodded. “I know.”

“And if I stay—” She stopped.

Cal didn’t finish it for her.

She looked up then, eyes tired but clear. “You’re not asking me to stay.”

“No,” Cal said.

“You’re not asking me to go.”

“No.”

She considered that.

For the first time since he’d known her, she smiled. Not polite. Not careful. Real, and brief, and gone too soon to hold.

“That matters,” she said.

Later, when the lamps were out and the saloon slept beneath them, Cal lay on his own bed and listened to the building breathe. The storm began to lose its edge sometime before morning, the wind easing as if it had said all it needed to say.

Above him, Lila slept—or rested, or simply lay still, learning what quiet felt like when it didn’t cost anything.

Cal stared at the ceiling boards and thought of winters that taught you what to keep.

Some shelter, he knew, wasn’t meant to last.

It was meant to give you just enough time to decide whether you were strong enough to walk out into what came next.

Chapter Nine — What Remains

The pass began to clear three days later.

Not all at once. First the wind shifted, coming down from the west instead of straight through the gulch. Then the snow eased into something lighter, less determined. By the fourth morning, Bitter Creek woke to a sky that showed its color for the first time in weeks—a thin, washed blue that felt almost unfamiliar.

Men came out of their cabins blinking, shoulders loosening like they’d been braced too long. Shovels appeared. Doors opened wider. Smoke rose steadier from chimneys that hadn’t given up after all.

The mine stayed shut. No one said when it would reopen. That kind of talk waited for warmer ground.

Lila packed without hurry.

Cal didn’t ask where she was going. He didn’t offer suggestions or routes. He let the space stay hers.

She borrowed a horse from a miner who owed Cal a favor he didn’t remember making. The animal was old but sound, its coat thick with winter. Lila ran a careful hand down its neck, murmuring something Cal couldn’t hear.

She wore the same coat, the same scarf. But she stood differently now. Not lighter—just steadier, like someone who’d shifted her weight and found it held.

They walked together as far as the edge of town.

The trail out of Bitter Creek cut narrow through the trees, a pale line where snow had been broken just enough to suggest direction. Beyond it lay miles of country that didn’t care who you were or what you carried, only whether you kept moving.

Lila stopped at the trailhead.

She turned once and looked back—not at the town, not at the cabins, not at the gulch—but at Cal.

She nodded.

It wasn’t gratitude exactly. It wasn’t farewell. It was acknowledgment. That something had been seen. That something had been allowed.

Then she swung up onto the horse and rode out, hooves finding their way where the snow still softened underfoot.

Cal watched until the trees took her shape apart and folded it into themselves.

He didn’t follow.

He went back to the saloon.

The Last Drift looked the same as it always had. Lamps cleaned. Tables wiped. Stove breathing heat into the room. Snow melting slow by the door, leaving dark, familiar marks on the floorboards.

Cal poured himself a drink.

He held it for a moment, then set it down untouched.

Outside, Bitter Creek moved again, freed just enough to be heard beneath the ice.

Snow still fell in the higher country. It always would.

By morning, the trail would be gone, covered clean, as if no one had ever taken it.

Cal stood in the doorway and watched the street settle into itself, feeling the quiet that followed something leaving—not empty, not full. Just changed.

Some winters, he knew now, were worth surviving.

Not because they ended cleanly.

But because they taught you what could be carried out of them—and what had to be left behind.