The year was 1910, and Laramie was already thick with the smell of coming rain and the sharper stink of coal smoke drifting in from the Union Pacific yards. Frontier Days had drawn its usual crowd: ranchers in faded chaps, drifters looking for day work, and a few city men in stiff collars who thought they’d see the real West for the price of a grandstand ticket. The rodeo grounds were a churned sea of mud and sawdust, the grandstands half-built and groaning under the weight of men who had nowhere else to be.

Early afternoon found Reed Callahan at a corner table in the Longhorn Saloon, the one with the tin roof that rattled whenever a train went by. He was forty-one, wiry and quiet, with the kind of eyes that had seen too many winters and not enough good ones. His coffee had gone cold an hour ago. He hadn’t touched it since the first sip.

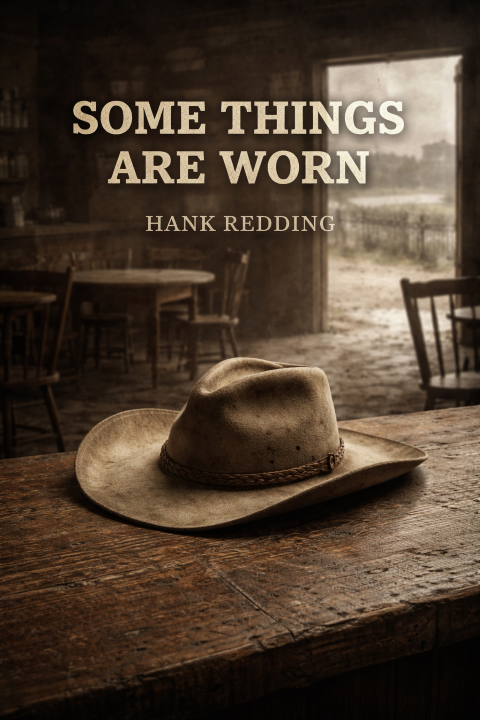

His hat sat on the table in front of him like a declaration.

It was a high-crowned felt, once pale as new snow, now the color of old parchment. The brim was wide and flat, edges slightly upturned from years of being shaped by hand and weather. A narrow band of rattlesnake skin—faded to a dull gray-brown—ran around the crown. A single eagle feather, tied with a strip of rawhide, dangled from the left side. On the right, a small silver concho shaped like a spur caught the weak light from the window.

Reed didn’t set hats down carelessly. This one had earned its place.

Across from him sat Jonas Pike, a man Reed had known since they were kids chasing strays along the Platte. Jonas was talking about a sorrel gelding that had bucked him off in Cheyenne two summers back, laughing the way men do when the hurt has finally faded. Reed listened, nodding now and then, letting the story run its course.

The saloon was busy but not crowded—cowhands nursing beers, a couple of gamblers arguing over cards, a piano player picking out a slow tune that nobody was really listening to.

Three men pushed through the batwing doors, bringing the smell of motor oil and scorched rubber. They wore leather coats cut short at the waist, heavy boots, and caps instead of hats. Their clothes carried the sharp tang of gasoline and the louder claim of men who believed speed made them invincible. Motorcycles had started showing up on the plains the last couple of years—loud, fast, and new. These three were riding them.

The tallest one—broad across the shoulders, mustache thick and waxed—spotted the hat on the table and stopped. He nudged his friends. A low laugh rolled out.

“Looks like somebody left their grandma’s bonnet on the table,” he said, loud enough to carry.

A few heads turned. Reed didn’t. He kept his eyes on the coffee cup, fingers resting light on the rim.

The man stepped closer, boots deliberate on the floorboards. “You mind if I borrow that, old man? See how it looks on a real rider?”

Reed lifted his gaze slowly. His voice was calm, almost gentle. “It’s not for borrowing.”

The scorcher grinned, glancing back at his companions. “Come on. It’s just a hat. What’s the story?”

Reed’s hand moved then—slow, careful—settling on the crown.

“This hat was my father’s,” he said. “He wore it the day he drowned trying to cross the North Platte in flood. I pulled it from the water myself.”

The room quieted another degree.

“The band came from a rattler my brother killed when he was seventeen,” Reed continued. “He was quick with a knife, quick enough to enlist when the trouble started down in Cuba. Never made it home. The feather was given to me by an old Shoshone man I worked cattle with one fall. He could smell snow before the clouds did. Somebody bushwhacked him outside Rawlins a few years later—no reason anybody ever found.”

He touched the silver spur with his thumb. “This was from a woman who rode drag with me on a drive to Montana in ’04. We talked about a place up near the Bighorns. She went on to California. I stayed. Never heard from her after that.”

The scorcher’s grin had faded. His friends shifted, eyes on the floor.

“You ride your machines hard across the flats,” Reed said quietly. “Maybe that’s your way. This hat is mine. It’s carried me through winters that killed better men, through stampedes, through nights when the only thing left was the will to keep breathing. If you put a hand on it, you’ll have to go through every mile it’s seen. And I don’t think you’re ready for that ride.”

Silence settled like dust after a hard wind.

The big man looked at Reed—really looked. Saw the rope scars on his wrists, the way his shoulders sat loose but ready, the calm that didn’t need to prove anything. He stepped back.

“Keep it,” he muttered. “Ain’t worth the argument.”

They turned and walked out. The doors swung shut behind them. The piano player started up again, a little louder this time.

Jonas let out a long breath and lifted his cup. “Some things you don’t touch.”

Reed nodded once. He picked up the hat, brushed an invisible speck from the brim, and settled it on his head. The feather caught the light as he stood.

Outside, the rodeo grounds were calling—chutes rattling, horses snorting, the low roar of a crowd waiting for the next man to test himself against gravity and time. Reed Callahan walked toward it, hat steady, carrying what he carried the way he always had.

Some things aren’t explained. They’re worn.