Chapter One — Useful

The horse came out of the chute wrong, and he knew it before the gate finished swinging.

It wasn’t fear. Fear had a rhythm to it. This was something older and meaner, the kind that didn’t burn off with movement. The bronc hit the ground hard, head low, shoulders driving forward instead of up, trying to run straight through the space instead of breaking against it. The rider lost his seat on the second jump and came off ugly, rolled once, then lay still in the dust with his hat ten feet away.

The crowd made a sound—not alarm yet, just surprise. That thin intake people gave when things didn’t go the way they were supposed to.

He didn’t look at the rider. Somebody else would. There were always boys quick to kneel, quicker to feel useful. He watched the horse.

“Easy,” he said, though the animal wasn’t listening and never had.

He stepped into the pen while the dust was still hanging, boots steady, movements economical. He’d learned years ago not to rush a horse like this, not to square up like it was a fight. You let them move. You let them think they were winning. Then you took away the part that hurt them most.

The bronc swung toward him, whites showing, sides heaving. He let it come close enough to feel the heat, then shifted just enough that the horse missed him and checked itself against the rail. Wood rattled. The horse snorted, confused now, looking for something solid to fight.

“Alright,” he said again, quieter.

Someone behind the fence called his name, half question, half warning. He didn’t answer. He had a rope in his hands and a job to finish.

By the time they got the horse settled, the rider was sitting up, embarrassed more than hurt. Blood from a split lip streaked his chin. He laughed too loud, waved off the medics. The crowd relaxed. A few claps came late, uncertain.

The contractor leaned over the rail. “That one yours?”

He nodded. “He’s green.”

The contractor snorted. “Aren’t they all.”

That was as close as anyone came to blame. The contractor moved on. The crowd forgot. The chute crew reset the gate. Another name was called.

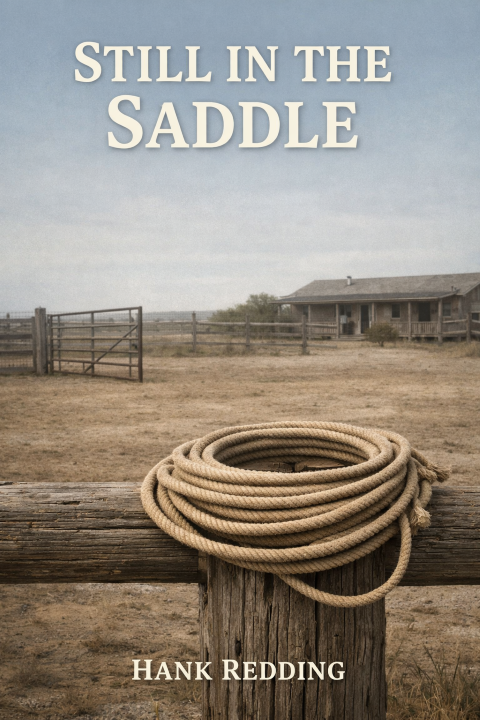

He coiled the rope and hung it back on the post, hands moving from memory. The horse stood in the far corner now, breathing hard, eyes dulling as the surge burned off. He watched the animal’s chest rise and fall and felt the echo of it in his own ribs.

“You alright?” a kid asked. One of the younger hands—maybe twenty—hat still clean, buckle bright.

“I’m fine.”

The kid nodded, satisfied, and jogged off. That was the exchange now. No deference, no dismissal. Just enough acknowledgment to keep things moving.

He wiped his hands on his jeans and stepped back from the pen. His knee twinged—sharp enough to notice, not sharp enough to stop him. He bent slightly, rolled it once, waited for the pain to decide what kind it was going to be today.

Across the grounds, trucks idled. Horses stamped. Dust settled, then lifted again. It was a small show—county-level, nothing that would make a paper outside of town—but the work was the same as it had always been. Horses didn’t know where they were. They only knew pressure and release.

He liked that about them.

By late afternoon the sun sat low enough to flatten everything, turning faces into silhouettes and fences into lines. He worked three more horses, none as bad as the first. The last one came around quicker than he expected, and for a moment—a small, dangerous moment—he felt the old satisfaction, the clean click of things going right because he knew what he was doing.

He held onto that feeling longer than he should have.

When the last rider came out and the crowd began to thin, he walked back toward the trailers. The contractor caught up to him near the water trough.

“You could head home if you want,” the man said, casual, like it didn’t matter. “We’re light tomorrow.”

He looked at the trough, at the thin line of water at the bottom reflecting sky. “I’ll stay.”

The contractor shrugged. “Suit yourself. There’s another stop in Amarillo next week. They might need you.”

“Alright.”

The man nodded and walked off, already thinking about something else.

He stood there a moment longer, watching the surface of the water tremble in the breeze. He thought about home—not as a place, but as a point on a map he kept folded in his head. He could picture the road without trying. The turnoff. The stretch where the pavement gave up and the land opened.

He told himself he’d go after Amarillo. One more week. One more check. One more thing finished the right way.

That was how he always put it.

He climbed into his truck as the light went and the first stars came out, pale and uncertain. The engine caught on the second turn. Somewhere under the floorboard, a bolt tapped in time, steady and familiar.

He drove toward the cheap motel on the edge of town, dust trailing behind him, already planning the next day’s work.

He did not think about writing.

He did not think about calling.

He thought about the horse that had come out wrong—and how, given another day, he could probably fix it.

Chapter Two — Letters

The motel had a vacancy sign that never changed—not because it was always full, but because nobody bothered to fix anything that still half-worked. The office smelled like stale coffee and floor polish. The woman behind the counter took his money without looking at his face, slid a key across the wood, and gave him the room number like she’d said it a thousand times.

He carried his bag in one hand. The other stayed loose at his side, fingers flexing now and then as if they were still holding rope.

Inside, the room was narrow and hot. A box fan sat on the dresser, pushing warm air in a steady, useless stream. He opened the window two inches and listened to the highway hum. Then he sat on the edge of the bed and unlaced his boots.

His knee throbbed in the quiet. So did his ribs—old injuries talking to each other. He pressed his thumb along one side and found a tender spot he didn’t remember earning. He tried to place it—rail, shoulder, some forgotten swing—but it didn’t matter. Pain was part of the deal. It wasn’t personal.

He washed his hands until the water ran clear. The soap was a thin bar with someone else’s hair stuck to it. He used it anyway. There were things in his life he didn’t get to be particular about.

At the small table by the window, he reached into his bag and pulled out the envelope he’d been carrying for two days.

It was addressed in a neat, familiar hand. His name centered, the ink pressed hard enough to leave a faint ridge.

He didn’t open it right away.

He set it down, smoothed the corners with his palm, and stared at it as if staring might make it lighter.

For years, her letters had been full of detail—what the neighbor’s dog had done, what the preacher had said, who’d gotten married, what eggs cost this week, what broke and who fixed it. He used to read them twice, sometimes three times. Not because he loved gossip, but because the specifics made the distance feel measured. Crossable.

Lately they’d gotten shorter.

Not angry. Not cold. Just reduced. The way a river thinned when the heat came and the source ran low. Fewer words. Fewer questions. More blank space between lines. He told himself it meant she was busy. He told himself things were steady.

He told himself a lot.

He opened the envelope carefully. Inside was one sheet of lined paper, folded once. No extra page. No note tucked inside. Just the one.

Saw your check today. Thank you.

That was the first line.

Something in his chest tightened—not pain, just a muscle that had gone unused too long.

He kept reading.

The roof held through last week’s wind. Jamie helped me patch the corner by the chimney. It isn’t pretty, but it won’t leak.

Jamie again. He pictured her easily—broad shoulders, tired eyes, steady hands. A person who showed up.

The truck is making that same noise. I’ll take it in when I can.

No mention of missing him. No be careful. No come home soon. No complaint either. Just information. Inventory.

The last lines were shortest.

Hope you’re well.

Be safe.

He read it again, slower, looking for what wasn’t there. Listening for her voice under the words the way he used to.

He couldn’t hear it.

He folded the letter along the crease and set it back on the table. The fan rattled on the dresser. Somewhere outside, a car door slammed. Men laughed in the parking lot. Life continuing without meaning to.

He reached into his wallet and took out the older letter, the one he carried like some men carried a lucky coin. The paper was brittle now, edges soft from handling.

She’d written it years ago, back when she still believed he needed reminding.

You can stay gone if you want, it said, blunt as a fence post. But don’t come home and act surprised when the house learns how to hold itself up without you.

He’d laughed when he first read it. Not because it was funny, but because it sounded like her trying to be tough. He’d kissed her forehead before leaving and told her she worried too much.

Now, in a room with thin walls and stale air, the line didn’t read like toughness.

It read like instruction.

He put the letter away and leaned back in the chair. The springs creaked. His knee complained. He ignored it.

He thought about calling.

The only phone was in the office. He could walk back, feed coins into the slot, listen to it ring across the distance. He could hear her voice—if she answered. He imagined the conversation the way he always did.

Him saying he was fine.

Her saying she was fine.

Both of them meaning something else.

He stayed seated.

Calling meant stepping into a space where he might hear something he couldn’t fix. He was good with his hands. He was not good with what lived behind someone’s eyes.

He paced the room once, then stopped at the window. In the parking lot, a truck idled with its door open. A man leaned against it smoking, head tipped back, throat exposed. Young. Loose in his body. The way he used to be.

He sat again and pulled out his notepad—the kind he used for feed orders and lists. He wrote her name at the top of the page and stared at the blank space beneath it.

What did you write when the truth didn’t fit on one page?

He wrote about Amarillo. About horses. About a kid who’d gotten tossed.

It read like a report.

He tore it out.

He tried again.

I got your letter. I’m sorry I haven’t—

He stopped. Sorry for what? Not writing? Not being there? Not choosing her? The truth stacked up behind the word like lumber you couldn’t carry in one trip.

He tore that page too.

In the end, he didn’t write anything.

He lay back on the bed fully dressed, boots off, hat on the nightstand, staring at the water stain spreading across the ceiling like a map of a place he’d never go.

Sleep came in pieces.

He dreamed of the practice pen back home—empty rails, dust lifting in the wind. In the dream, a horse breathed somewhere close, but every time he turned there was nothing there.

Morning arrived hard and bright. His body felt old. His knee was stiff. Outside, trucks started, men leaving for work that didn’t require feeling.

He washed his face, packed his bag, folded her short letter, and slipped it into his wallet behind the faded photograph. He didn’t throw it away. He wasn’t ready to treat it like trash.

Before leaving, he paused at the table. The notepad lay open.

Her name sat at the top of the page, alone.

He closed it and put it back in his bag.

Outside, the air already carried dust. In an hour the grounds would wake. Horses would buck. Men would shout. The world would do what it always did—move forward without apology.

He started the truck. The bolt under the floorboard tapped its steady rhythm.

As he pulled onto the road toward the arena, he told himself he’d write tonight.

He told himself he’d call when he had time.

He told himself he’d be home soon.

And because he’d been telling himself those things for years, the lie slid into place like a familiar saddle—worn, comfortable, and dangerous.

Chapter Three — Switch

The horse was waiting for him before sunrise, because trouble didn’t sleep and neither did the men paid to manage it.

The grounds were quiet in that early hour, bleachers empty and pale, chutes dark against the thinning night. A few lights burned over the stock pens, yellow and tired. Somewhere a radio played low in a tack trailer—a man’s voice reading the weather like it mattered.

He walked with coffee in one hand and his hat pushed low, shoulders loose, moving like a man who’d learned not to waste anything, even steps. His knee warmed as he went, complaining less once it remembered its job.

The contractor met him at the pens, boots planted wide, arms crossed. He didn’t offer a handshake. Men like that saved handshakes for deals and funerals.

“Got one for you,” the contractor said.

He took a sip of coffee and looked past him.

The horse stood alone in a small holding pen, separated from the rest like a thing quarantined. It wasn’t big—not the way the real wreckers were—but it carried itself with a sharpness that made size irrelevant. Dull sorrel hide under the lights. Mane chopped uneven. Ears pinned back even when nothing threatened it. Eyes fixed, not wild—deciding.

It wasn’t fear.

It was refusal.

He watched the horse shift its weight, saw the pattern: not nervous, not jittery. A readiness to explode when it chose.

“What’s his name?” he asked.

“They’re calling him Switch,” the contractor said.

He nodded once. It fit.

“Where’d he come from?”

“Arizona string. Guy down there says he’s got spirit.”

“That’s what they call it when it costs money.”

The contractor laughed, short and dry. “Three riders in two nights. One kid broke his collarbone.”

He didn’t react. He’d seen broken bones. Had a few of his own. He watched Switch and let his mind catalog what mattered—the hips, the shoulder angle, the way the head stayed set. A scar along the flank. Old rope burn. A memory of force.

“He ain’t mean,” the contractor said. “Just wants his way.”

“So do most things.”

The contractor leaned closer. “You can’t get him right, we pull him. I’m not paying hospital bills for pride.”

“I’m not proud,” he said, and meant it. Pride was for riders and politicians. He worked.

He set his coffee on the rail and stepped closer. The horse swung its head toward him, eyes hard. He didn’t reach out. Reaching out got you bit. Not always in the hand.

He waited. The horse shifted, uncertain what to do with a man who wasn’t trying to dominate it.

“That’s a bad one,” a voice said behind him.

He didn’t turn right away. When he did, the kid from yesterday stood there—bright buckle, clean hat, twenty years old and already talking like he had a past.

“Name’s Dale,” the kid said. “They say that horse is a killer.”

“He hasn’t killed anyone.”

“Yet,” Dale said, grinning.

He turned back to the horse.

“You train him different?” Dale asked.

“I train him the way he is,” he said. “Different horses, different hands.”

Dale leaned on the rail. “Guy down in Pecos used a burlap sack on a pole. Gets ’em used to movement. Makes ’em quit quicker.”

The irritation rose, quiet and familiar. Not anger. A reflex. The feeling of being corrected by someone who hadn’t earned the right.

“Burlap don’t teach a horse anything,” he said. “Just scares him in ways you can’t control.”

Dale shrugged. “Just saying.”

That was the thing about young men. They said. They offered. They spoke into spaces that weren’t theirs, then walked away light, because consequences hadn’t found them yet.

He reached for his rope.

Working a horse like this wasn’t about riding. It was handling. Routine. Making the world smaller. Removing choice without force.

He stepped into the pen. Switch tensed, muscles gathering. He didn’t rush. He angled his body, claimed space without charging. The horse circled, head low, testing.

“Easy,” he said.

Switch snapped its head toward him. Warning, not panic.

He kept moving. The horse tried to stop and square up. He shifted, stepped, kept it going—steady, continuous. He wasn’t trying to tire it. He was taking away control.

Minutes passed. Dust rose. The light thinned from blue-black to gray.

Switch flicked an ear forward.

A small thing. A crack.

He swung the rope gently, letting the loop drag, letting the sound become ordinary. The horse watched, muscles tight, but didn’t bolt.

He felt eyes on him—Dale’s, the contractor’s. Men always wanted victories they could see.

When he tossed the loop, it settled clean over the horse’s neck, like it belonged there. Switch exploded anyway—lunging, throwing weight back.

He let it.

Not fully. Not without control. Enough for the horse to feel its strength—and the boundary waiting for it.

Switch hit the end of the rope hard, fought, blew snot, threw its head until the rope bit and resistance turned painful.

He held steady.

Not cruel. Just unmoving.

After a long minute, the horse stopped. Trembling. Breathing. Listening.

He stepped closer, coiled slack. “That’s it,” he said. “That’s it.”

He didn’t pet the horse. He didn’t soothe it. He let his presence become unavoidable—and then ordinary.

Switch followed when he led it out. Stiff, reluctant. But following.

The contractor raised his brows. “Well I’ll be damned.”

He tied the horse in the larger run, checked the knot twice, stepped back.

“You make it look easy,” Dale said.

“It isn’t.”

Dale grinned. “Still. You got a gift.”

He looked at the kid and saw something else there—not arrogance, not disrespect. Hunger. The belief that there was a place in the world if you learned the right tricks.

“You ride?” he asked.

“Some. I can sit one.”

“Can you sit that one?”

Dale’s grin faltered, then came back thinner. “Maybe. With the right flank.”

“He ain’t ready.”

“You saying I’m not?”

“I’m saying the horse ain’t ready.”

The contractor laughed, approving. “Listen to him, kid. He don’t care about your pride.”

Dale looked away.

Switch stood tied, head lowered, sides still working. The horse’s eye rolled, tracking him. Not trust. Not yet. But recognition.

That familiar satisfaction settled in—the clean click. A problem held. A system made stable.

It made him feel useful.

And usefulness, he’d learned, was a dangerous comfort. It told you you mattered, even when you weren’t where you were supposed to be.

He checked his watch. Early still.

He could have gone home then. Taken the quiet roads. Been there by late afternoon. Stepped onto the porch before the day was gone.

He pictured it—her turning, startled, wiping her hands on her apron, eyes narrowing like she didn’t trust it.

Then he looked at Switch again.

The horse shifted, testing the rope. Still unfinished.

One more day, he thought.

He drank the last of his coffee—cold now—and turned back to work.

Chapter Four — Hold

By the third day, the grounds had learned his rhythm.

Men nodded when he passed. Not greeting exactly—recognition. He moved through the pens before the sun cleared the horizon, coffee cooling on the rail, rope already in hand. Switch came to the gate when he approached, ears no longer pinned, eyes still hard but no longer searching for a way out.

Progress, then. The kind you could point to without exaggerating.

The contractor noticed. So did everyone else.

“You might have him broke by Friday,” someone said, admiration folded into the words like it didn’t want to be accused of anything.

He didn’t answer. He never promised timelines on living things.

Switch fought less each morning, but the fight he kept was smarter. He learned where the rope would bite, where it wouldn’t. How to stop just short of pain. A calculating horse—the worst kind and the best, depending on whose hands he ended up in.

He saw himself in that learning and didn’t like it.

Late that afternoon the heat turned punishing. The sun pressed down like it had a grievance. Dust stuck to sweat, turned skin gritty. He was leading Switch through the outer run when the horse shied at nothing—nothing he could see—and jumped sideways into the rail.

The rail snapped with a sound like a gunshot.

He felt the hit before he understood it. Wood drove into his thigh, sharp and blunt at once. His knee buckled. He went down on one hand, the rope burning through his palm as Switch pulled back, panic breaking through the discipline he’d been building.

Someone yelled.

He rolled, held the rope long enough to keep the horse from breaking free, then let it go before it took his shoulder with it. Switch tore loose, skidded, and bolted for the far end of the pen, throwing dust and noise behind him.

He lay still, face pressed into dirt that smelled like iron and sweat, and waited for the pain to decide what it was going to be.

It chose sharp.

Hands grabbed his arms, hauled him halfway up before he waved them off. “I’m alright,” he said out of habit.

“You ain’t,” someone said. “Sit.”

He sat.

The contractor pushed through, face tight. He looked at the broken rail, then at the blood darkening his jeans. “You bleed?”

“Looks like it.”

They got him into the shade of a trailer. Water appeared. A rag. The rider with the broken collarbone hovered nearby, pale and eager to matter again.

The contractor crouched and peeled the denim back. The cut was deep but clean—wood having done what it always did, straight in and straight out.

“You need stitches,” the contractor said. “Town’s ten miles.”

“Wrap it for now.”

“You sure?”

“I’m sure.”

The contractor hesitated, then turned away, already calling orders about the horse, the rail, the schedule. The show didn’t pause for blood.

They wrapped his leg tight. Someone handed him his hat. He settled it on his head, the familiar weight pulling him back into himself.

He stood slowly. Pain flared, then settled into a heavy ache.

Manageable.

“You want me to take you in?” Dale asked, hovering now, concern genuine and inconvenient.

“No.”

“You shouldn’t—”

“I said no.”

Dale stepped back.

He walked to his truck under his own power, each step deliberate. Inside, the cab smelled like oil and dust and old coffee. Familiar. He sat with his hands on the wheel until his breathing evened.

In the mirror, the grounds looked smaller than they felt. Men moved with purpose, already adjusting around his absence.

He started the engine.

At the edge of town, the turnoff toward home appeared. He slowed without meaning to. The road lay open, pale and empty, stretching toward a place he hadn’t stood in months.

He pictured the porch. The swing. The screen door breathing.

His leg throbbed.

The clinic sat ahead—a low concrete building, faded sign, single cottonwood out front. He turned that way instead.

Inside, the nurse worked without comment. She cleaned the wound and stitched it tight, quick and practiced. He watched the needle go in and out, pain clean and predictable.

“You should stay off it,” she said, tying the last knot. “Few days at least.”

“I can’t.”

She looked at him the way people did when they already knew the answer. “Then keep it clean.”

She wrapped it again and handed him a slip of paper he didn’t read.

Outside, the sun had dropped low enough to feel like mercy. He stood there a moment, leg stiffening, and understood something clearly.

The injury gave him an exit.

A legitimate one. He could go home. Say the work had put him down for a spell. Arrive wounded and be forgiven before he opened his mouth.

That was the danger of injuries—they turned choices into stories you could tell yourself without lying.

He didn’t leave town.

He drove back to the grounds and watched Switch from outside the pen, one hand braced on the rail. The horse stood quiet now, subdued by its own panic. A handler moved nearby, cautious.

“He ain’t done,” the contractor said.

“No.”

“You sure you’re up for this?”

He shifted his weight. Pain answered, sharp and honest. “I am.”

The contractor studied him, then nodded. “Alright. But we take it slow.”

They did. For a day.

By the second, slow had turned into normal.

By the third, the leg had swollen and the stitches pulled tight every time he bent it. He ignored that too.

At night in the motel, he lay with his leg propped on a pillow and stared at the ceiling. He told himself he’d go home once Switch was settled. He told himself coming home limping wouldn’t help anyone.

He told himself she’d understand.

A letter came the next morning, forwarded from the grounds office. Short again.

Jamie’s truck is fixed. I’ll be using it for a while.

No questions. No urgency. No mention of him.

He folded the letter and put it away.

The work filled the days. The pain filled the nights.

Somewhere between the two, leaving stopped feeling like a plan and started feeling like a story he’d once heard and half-believed.

He stayed.

And because staying had always worked before, he trusted it to work again—never noticing that the thing he relied on had already stopped being true.

Chapter Five — Through Amarillo

Dale got hurt on a Thursday, which felt appropriate in a way he couldn’t have explained.

The week had settled into something almost workable. Switch no longer fought the rope outright. The horse tested, resisted, then gave ground in increments so small they looked like accidents. Progress you had to earn the right to notice. He liked that kind best.

His leg did not.

The stitches pulled every time he stepped sideways, every time he shifted too fast. Swelling came and went like weather. He wrapped it tighter each morning, took the pills the nurse had given him without enthusiasm, and went on.

By Thursday the heat was relentless, the kind that pressed down on men until they grew careless. Horses felt it too. They came out hot, muscles tight, tempers short.

Dale drew Switch in the late afternoon.

He heard it before he saw it—a murmur near the board, a small surge of interest. Dale stood a little straighter than usual, hat set just so. He caught his eye across the pens.

“You sure?” Dale asked, trying to sound casual.

“He’s been quiet,” he said. “You sit him clean. Don’t rush.”

Dale nodded, the way young men did when they planned to rush anyway.

He watched the flank get set, watched the rope go on. Switch stood still in the chute, head low, breathing slow. Too slow. A calm that felt like a held breath.

He leaned in. “You feel him start to lean,” he said quietly, “you give him room. Don’t fight the first jump.”

Dale smiled, quick and bright. “I got him.”

The gate swung.

Switch came out straight and hard, then snapped sideways in a way that wasn’t quite bucking, wasn’t quite twisting—something new. Dale’s seat broke immediately. He hung on for half a second, maybe less, then went off backward, head and shoulder hitting first.

The sound was wrong.

The crowd reacted—alarm sharp and immediate. Men were already moving. He moved without thinking, leg screaming, body leaning into old reflex. He reached Dale before anyone else did.

The kid lay on his side, breath coming fast and shallow, eyes wide.

“Don’t move,” he said. He put a hand on Dale’s chest, felt the uneven rise. “Where you hurt?”

“My arm,” Dale said. “It ain’t right.”

He followed the line of the shoulder. The angle was wrong. Bone where it didn’t belong.

“Look at me,” he said.

Dale did. Fear cut through the bravado. “I messed up.”

“No,” he said. “You got unlucky.”

It wasn’t entirely true. But it was what the kid needed.

They loaded Dale into the ambulance. The crowd thinned again, disappointed now instead of shocked. The contractor stood beside him, jaw tight.

“That’s two injuries on that horse,” the man said. “I’m done gambling.”

“He ain’t finished.”

The contractor turned on him. “You are.”

The words landed heavier than he expected.

“You’re limping like a bad habit,” the contractor said. “I’ve got a rider in a sling and a schedule that doesn’t stop. You should’ve pulled him.”

He said nothing. There were too many answers, and none of them mattered.

The contractor rubbed his face. “Amarillo starts Monday. I don’t have another trainer lined up. Dale’s out. I need you.”

The tightening came then—the familiar one, when need got dressed up as obligation.

“You stay through Amarillo,” the contractor said. “Get Switch settled enough he doesn’t kill anyone. After that, we’ll talk.”

He looked past the pens to the road, pale and open.

He thought about the clinic. The stitches. The folded paper the nurse had handed him. He thought about the letter in his wallet. Jamie’s truck. For a while.

“How long is Amarillo?” he asked.

“Five days,” the contractor said. “Six if weather turns.”

Five days became a shape he could carry. Not long. Not forever. Manageable.

“Alright,” he said.

Relief replaced concern on the contractor’s face. “I’ll owe you.”

He almost laughed. Owing didn’t mean what it used to.

That night in the motel, he unwrapped his leg. The stitches were red and angry, skin pulled tight. He cleaned the wound slowly, the way you did when you were alone with consequences.

The phone sat on the nightstand. Heavy. Real.

He picked it up, dialed halfway, then stopped.

I stayed again.

I got hurt.

I’m needed.

He set the receiver down.

Instead, he wrote.

Staying on through Amarillo.

Horse needs work. Shouldn’t be too long.

After a moment, he added:

Hope everything’s alright.

He sealed the envelope. He would mail it in the morning. It felt like action. It felt like communication.

It was neither.

The next day they loaded up and headed west, dust trailing behind the trucks in long, patient lines. The land flattened, then rose, then flattened again. His leg throbbed with every mile.

Switch traveled quietly now, head low in the trailer, the fight turned inward. He drove with one hand braced against the dash, watching the road unwind.

South of the Red River, another turnoff appeared—the one that would have taken him home.

He didn’t slow.

By the time they crossed into Texas proper, leaving had narrowed into something fragile—less a plan than a hope he didn’t trust.

Amarillo waited.

And with it, the last good reason to stay.

Chapter Six — Eight Seconds

Amarillo had the look of a place that expected things from you.

The grounds were larger than the last stops, bleachers taller, chutes newer. Trucks lined up in orderly rows like they’d been told where to stand. The air smelled of hot oil and trampled grass. This wasn’t a county show anymore. It was business.

He felt it the moment he stepped down from the truck.

Men moved with purpose—clipboards, radios, schedules pinned to corkboards. There was less talk and more watching. Less patience for anything that didn’t perform on time.

Switch came off the trailer tight but controlled. The horse took in the space with quick glances, ears flicking, hooves striking dirt in short, sharp steps. The fight was still there, but it had changed shape. Not explosive now. Contained.

That worried him more than open resistance ever had.

They worked early the first morning, before the heat settled in. His leg protested immediately. The stiffness had turned into a deep, pulsing ache that didn’t fade once he got moving. He wrapped it tighter, told himself it was travel, routine, nothing new.

He’d made worse work hurt less. He told himself that too.

The contractor hovered. “We need him steady,” he said, watching Switch move through the pen. “No room for surprises.”

“No horse does,” he said.

Switch tested him again, not with force but timing—leaning as he shifted, stepping into space that should’ve been clear. A clever horse. Learning the gaps. The kind that made a man feel older than he was.

“You’re thinking too much,” a voice said from outside the rail.

He didn’t turn. Dale’s replacement. Another kid. Lean. Confident. Already settled into himself.

“I’m thinking enough,” he said.

“You ever just let one fight it out?”

He guided Switch through another slow circle, rope steady. “That ain’t training,” he said. “That’s gambling.”

The kid shrugged. “Crowd likes a gamble.”

He didn’t answer. The crowd went home. Horses didn’t.

By midday, his leg went numb in a way that worried him—dull, spreading. He leaned heavier on the rail than he meant to, breath controlled.

“You should sit,” the contractor said quietly.

“In a minute.”

That minute stretched into an hour.

The afternoon ride went smoother than he expected. Switch came out hard but straight, bucked clean, no tricks. The rider—young, cautious—sat it through without showmanship.

Eight seconds.

Clean dismount. No injury.

The crowd clapped. Not loud. Appreciative. The contractor exhaled.

“That’s it,” the man said. “That’s what we need.”

He nodded. He should’ve felt relief. Instead, something in his chest tightened. Switch had learned enough to be useful.

Which meant the work was nearly done.

That night in the motel, his leg demanded attention. When he unwrapped it, the skin around the stitches was swollen and hot, red spreading outward in a way he didn’t like.

Infection was a word he knew. A thing other men got. A thing you dealt with when it arrived.

He cleaned the wound and wrapped it tighter. Pain cut sharp this time. He breathed through it, slow and practiced.

The phone sat on the nightstand.

He picked it up, heavier now. Dialed from memory. Stopped. Then finished.

The ring traveled a long way before it came back.

Once.

Twice.

On the third ring, she answered.

“Hello?”

Her voice was thinner than he remembered. Or maybe he’d been carrying an older version of it too long.

“It’s me.”

A pause. Just long enough to register.

“I know,” she said.

He waited. Nothing followed.

“I’m in Amarillo,” he said. “Working through the week.”

“I figured.”

He leaned back, stared at the ceiling. “I got hurt,” he said. “Nothing bad. Leg.”

Another pause.

“Are you alright?”

“I will be.”

Silence again. Not empty. Considered.

“Jamie took me into town yesterday,” she said. “I’m staying with her some.”

The words landed softly. Too softly.

“For how long?”

“I don’t know. A while.”

“I’ll be home soon.”

She didn’t answer right away.

When she did, her voice was gentle in a way that felt like distance, not care. “You always are.”

The line went quiet.

He held the receiver until the silence decided for him, then set it back in place.

The room felt smaller afterward, as if the walls had shifted a fraction inward. He sat there a long time, hands resting uselessly in his lap.

The next morning, the contractor told him Switch was drawing again.

“He’s ready,” the man said. “You did your job.”

He nodded. The words sounded like praise. They felt like release.

He watched Switch that afternoon from the fence, one hand gripping the rail until his knuckles went white. The horse came out steady, did what it had learned, and left the arena without incident.

The crowd clapped louder this time.

He did not.

That night he lay awake and listened to trucks come and go, engines starting and stopping, men leaving for lives that were waiting.

He thought about the porch.

The swing.

The screen door.

He thought about the phone call—how finished her voice had sounded.

And for the first time in years, going home did not feel like relief.

It felt like something he might already be too late for.

Chapter Seven — Released

The circuit ended without ceremony.

There was no final whistle, no gathering of men to shake hands and mark the thing as finished. Trucks loaded and unloaded. Papers were signed. Horses were moved like inventory. By Sunday morning the grounds had already begun to empty, the work dissolving into logistics.

He stood near the pens and watched Switch load into a trailer bound for somewhere else. The horse went up the ramp without trouble, hooves ringing hollow, head low.

It didn’t look back.

That was the way of it. Horses didn’t carry grudges. They learned what they needed to survive and left the rest behind.

The contractor found him near the gate an hour later, hat in hand, sunburned and already thinking ahead.

“You did right by me,” he said. “I appreciate it.”

He nodded. Appreciation was a word that wore thin quickly.

“I don’t need you past today,” the contractor went on. “If you want, there’s a fall string out near Flagstaff. They’ll need hands.”

The old instinct stirred—motion as answer, distance as solution.

“I’ll think on it,” he said.

The contractor glanced at his leg, the careful way he stood. “You should go home.”

It wasn’t advice. It was observation.

“Yeah,” he said.

The contractor hesitated, then handed him an envelope. “This’ll square us.”

He took it without checking inside. He’d learned not to count money in front of other men. It changed the air.

They shook hands—brief, workmanlike. The contractor moved off, already calling to someone else.

He stood there a moment longer, then walked back to his truck.

The drive out of Amarillo was slow. Traffic thinned. Buildings gave way to open land. He rolled the window down and let the wind in. It smelled like dust and sun and nothing else.

His leg throbbed in time with the road.

He told himself he would drive straight through.

No stops. No delays.

That the house would look the same.

That whatever shift had happened could still be stepped back into with enough care.

Outside town, he passed a diner advertising pie. He slowed, then kept going. He wasn’t hungry. Or maybe he didn’t trust hunger anymore.

The road unwound. Hours passed.

By late afternoon the light slanted low, the day thinking about ending. He stopped once for gas, once to stretch his leg, once because the pain demanded it. Each stop cost him minutes he couldn’t afford but couldn’t avoid.

At the second stop, a man leaned against the pump. “You heading south?”

“Yeah.”

“Storm coming,” the man said, nodding at the sky.

Clouds gathered in the distance, tall and dark but still far enough away to feel theoretical.

“I’ll be alright,” he said.

The man shrugged. “Suit yourself.”

He drove on.

The land narrowed in ways he felt before he saw. A bend in the road. A stand of trees he remembered. The sense of approaching something fixed.

For the first time since the circuit let him go, he did not feel pulled forward by the next job or the next place.

There was nothing left to finish.

He followed the road as it bent south, believing—quietly, without argument—that what waited at the end of it was still his to return to.

Even so, he did not feel ready to cross the last distance all at once.

Chapter Eight — Habit

He slept in the truck that night.

Not because he couldn’t bring himself to stop yet, and not because there was anything he knew for certain that would have hurt him if he did. He slept there because it was what he knew how to do when the world stopped making requests.

The rain left behind a damp cold that crept up from the ground. He kept the windows cracked and his coat pulled tight, one arm folded awkwardly to spare his leg. Sleep came in shallow stretches. He woke often, listening to the quiet, expecting—without knowing why—to hear footsteps or the soft clatter of dishes somewhere nearby.

Nothing moved.

At dawn the land looked scrubbed raw. The ground steamed faintly. Drops clung to the wire fence along the road and caught the light. He pushed himself upright slowly, joints stiff, leg aching with a deep, settled pain that felt older than the injury itself.

For a moment he considered stopping for good.

Making coffee.

Sitting at a table like the place still belonged to him in a way that mattered.

Instead, he started the truck.

The engine complained, then caught. The familiar rattle returned, the tapping under the floorboard steady and unremarkable. He let it idle a moment, then pulled back onto the road.

The morning was quiet—the kind that followed weather and decisions. He drove without hurry, letting the miles stack up without counting them. Past the turnoff. Past the feed store. Past the places where a life had once been anchored to something other than motion.

By midmorning he stopped at a roadside café he’d eaten at before. He took a stool at the counter, ordered coffee, and let it sit while he looked out the window.

The waitress recognized him without knowing him. That was how it worked in places like this.

“You passing through?” she asked.

“Yeah.”

“Where to?”

He opened his mouth, then closed it again. The question weighed more than it should have.

“Not sure yet.”

She nodded. “Road’s good today.”

He drank the coffee. It tasted burnt. He paid, left a tip that felt excessive, then stood outside with his hands on the hood, feeling the engine’s warmth through the metal.

He thought about the fall string near Flagstaff. The contractor’s offer. How work always made itself available if you didn’t ask too many questions.

He thought about Switch, already somewhere else, already belonging to a new routine.

He thought about the house—not as a place, but as a presence he’d driven away from without understanding why.

For the first time in years, the road ahead did not feel like escape.

It felt like habit.

He drove.

The day wore on. The land flattened, rose, flattened again. He stopped when his leg demanded it, stretched carefully, leaned against the truck and waited for the pain to settle into something tolerable.

At one stop, he noticed a small rodeo poster taped to a gas station window. A date circled in pencil. A phone number written underneath. The kind of thing he used to tear down and fold into his pocket without thinking.

He studied it for a long moment.

Then he left it where it was.

By evening the light thinned, the sky paling toward the color that meant the day had done all it was going to do. He pulled onto a dirt road near a low rise, cut the engine, and sat in the quiet.

The wind moved through the grass, familiar and unremarkable. Somewhere far off, a train horn sounded—long, low, not calling anyone in particular.

He rested his hands on his thighs and felt the ache there, the honest accounting of years spent doing one thing well and nothing else.

For a long time, that had been enough.

Now it wasn’t.

He didn’t cry. He didn’t pray. He didn’t make promises he wouldn’t keep.

He sat until the stars came out, then until they brightened, then until the world settled into its night shape.

When he finally closed his eyes, it wasn’t with hope or fear.

It was with the plain understanding that some things you trained too late—and some doors you learned to open only after you’d already passed them by.

Knowing that didn’t change what came next.

It only made it quieter.

Chapter Nine — Stay

Morning came without asking.

Light crept up from the east and found him where he sat, hat tipped low, hands resting in his lap. His leg had stiffened in the night, the ache deep and settled now, like it had decided to stay awhile. He waited it out, breathing slow, letting his body wake on its own terms.

He had learned patience the hard way.

He drove again—not early and not late—just when it made sense to move. The road carried him past towns he knew only by the shapes of their water towers and the bends in their main streets. He stopped when hunger announced itself, when gas ran low, when his leg demanded it. No hurry. No destination worth naming.

By midafternoon he found himself on familiar roads without remembering when he’d chosen them. The land narrowed in a way he recognized—fences farther apart, cattle standing still in the shade. It felt like returning, even though he’d already done that once and learned what it cost.

He pulled off near a small yard where a man was working a rope with a young horse. Nothing serious—just teaching it to stand, to feel pressure without panic. The work was clumsy but honest. The man’s movements lacked economy, but there was patience in them.

He watched from the truck for a while, engine idling.

The rope slipped. The horse jumped, startled. The man swore, laughed at himself, gathered the slack, and tried again. No anger. No show. Just persistence.

It struck him how little room he’d ever given himself to be bad at anything—how quickly he’d moved on when mastery failed, instead of staying long enough to relearn.

He shut off the engine and stepped out.

The man noticed him and lifted a hand. “Afternoon.”

“Afternoon.”

“You know horses?” the man asked—hopeful, but not desperate.

He looked at the rope, the uneven coil, the knot set wrong. The old instinct stirred, automatic and precise.

“A little.”

“You got a minute?”

He had more than that. He had time now, whether he wanted it or not.

He stood beside the pen, careful of his leg. He didn’t take the rope right away. He watched the horse breathe, watched the man’s hands, listened to the quiet between movements.

“Don’t pull so hard at first,” he said. “Let him feel it before you ask.”

The man nodded and tried again. The horse settled quicker this time, confusion easing into something steadier.

“Like that,” he said.

They worked awhile—small corrections, patient listening. It felt different than training riders. Slower. No audience. No performance. Nothing at stake but the moment.

When they finished, the man wiped his hands on his jeans. “You ever think about hiring on?”

He almost laughed.

“Not anymore.”

The man nodded. “Well. Appreciate the help.”

He tipped his hat and walked back to the truck.

As he drove off, he realized something had shifted—not resolved, not healed. Repositioned. The work no longer owned him. He could touch it without letting it decide where he went next.

That evening he stopped outside a town small enough that the motel doubled as a bar and the bar doubled as a place to hear news. He took a room, washed the road off his face, and sat on the bed with the window open.

Voices drifted up from below. Laughter. A radio. Someone arguing good-naturedly about a game he didn’t follow anymore.

He took out his wallet and removed the letters—both of them. The older one with its warning. The newer one with its restraint. He read them in order, then folded them and returned them to their place.

They didn’t accuse him.

They didn’t forgive him either.

Later, when the light went, he lay back and stared at the ceiling. He thought not about what he’d lost, but about what remained now that he wasn’t chasing the same ending again and again.

There would be another morning. Another road. Another decision that didn’t need explaining.

That was the difference.

He slept deeper than he had in months.

When he woke, he knew where he was going—not in miles or names, but in terms of pace. Slower. Closer. Present in ways he’d never trained for.

He did not yet know where that kind of staying would matter.

What came next would not ask him to prove anything.

It would only ask that he stay.

Chapter Ten — The House

He came in on a Tuesday, because he’d never been good at arriving when anybody was waiting.

The highway out of Oklahoma laid down into Texas like a tired ribbon, and by the time the sun began to fall the light had that flat, bleached look it got in late summer—like the whole country had been rinsed and left out to dry. His truck rattled in a way he’d come to think of as normal. A bolt somewhere under the floorboard tapped in time with the engine, steady and unhurried. His leg held a deep, settled ache now—not sharp, not demanding—something he’d learned to move with instead of against. He told himself he’d fix the bolt when he got home.

He’d told himself a lot of things like that.

He took the county road because he always did—not because it was faster, but because it felt like coming in the back door instead of being seen. Mesquite and scrub slid past. Then the land opened and the wind had room to do what it wanted. Dust moved in slow sheets across the caliche. He let the truck idle there a moment longer than he needed to, hands resting on the wheel, listening to the bolt tap its time for something that had already happened.

The house sat where it always had—set back from the road, low and plain, porch boards silvered by sun. For half a mile he watched it grow in the windshield, waiting for the small signs his mind had kept alive: her in the yard, her on the steps, the screen door breathing once and then slapping shut. He pictured her the way he always did when he was too far away to remember clearly—hair pinned up, hands busy, face turned toward him like he belonged to the same place she did.

Nothing moved.

No smoke from the chimney. No wash on the line. The porch swing sat still, chain slack, as if it hadn’t been touched in weeks. The yard had been cut recently, though. That gave him a thin kind of relief. Not abandoned, then. Kept.

Kept by who, he didn’t ask. He was not a man who volunteered questions.

He drove past the front, then eased around to the side where gravel gave up to dirt. He shut off the engine. The quiet pressed in until he heard his own joints settle. Somewhere behind the house a windmill creaked once, lazy and unhurried.

He sat longer than he meant to, hands on the wheel. His thumb rubbed the cracked leather without thought, the way it did around reins—a habit of holding on after the work was done.

When he stepped down, heat came up through the soles of his boots like the ground had been saving it. He walked slowly, because his knee didn’t like quick anymore, and because there was no hurry that could change what had already happened.

The screen door didn’t slap. It hung open two inches. He pushed it with two fingers. It moved without protest.

Inside, the air was cool in that stale way houses got when they’d been closed up—cool but not alive. He stood in the entry while his eyes adjusted. The living room looked the same at first glance—the couch with the faded throw, the lamp with the crooked shade, the small table by the window. But the room carried a different balance, like weight had been shifted.

He set his hat on the chair without thinking. It looked wrong there—too new in a room that had learned to live without it.

At the table by the window there was no stack of letters. No grocery list. No note. Just a clean ashtray and a single key resting on a square of brown paper.

The paper wasn’t a note. It was folded like a receipt. He opened it carefully, expecting words the way a man expects pain when he presses a bruise.

It was a receipt. Her name. The feed store in town. Dated three weeks ago.

He studied it as if it might explain something. Then he set it back exactly where it had been.

The kitchen was bare. No dish towel. The kettle gone. The coffee jar half full and old. Her chipped mixing bowl missing.

A man can ignore a lot until the small things line up.

The icebox held almost nothing. He closed the door and rested his palm on the metal, as if the cold might steady him.

The bedroom door stood open. The bed was made. One pillow. The dresser cleared except for a hairbrush placed handle-out. Her drawer empty—he didn’t pull it open all the way.

In the closet, his shirts still hung spaced the way she’d always spaced them. His coat on its hook. His spare boots lined beneath. On her side, two dresses remained: a plain day dress and the black one for funerals and Sundays. The rest of the hangers were turned backward, like someone had tried to make absence look intentional.

He shut the door softly.

In the spare room, boxes were stacked neat and labeled in her hand: Kitchen. Books. Linens. Pictures.

One strip of tape read: To Jamie’s.

He knew Jamie—the widow on the north road. A decent woman.

So that was it. No scandal. No new man. No story anyone could point at and feel righteous about.

Just a decision, carried out in daylight.

He sat on the edge of the bed without meaning to. The mattress dipped. His knee complained. He let it.

The house settled around him, boards shifting as the heat changed. It sounded like breathing.

He thought about bunkhouses and tack rooms, boots still on, telling himself the next check would make it right. The next circuit. The next horse.

He’d measured love the way he measured work—by what he could endure, provide, fix with his hands.

And she—she had endured. Quietly enough that he’d mistaken it for agreement.

He returned to the kitchen and picked up the key. The small house key—the one she kept separate because it saved time.

She’d left it like a courtesy.

He set it down again.

Outside, the small pen stood empty. The rope he’d left looped over the rail was still there, stiff with dust. He lifted it, felt the familiar weight. The fibers crackled softly. He could still throw it. Of course he could.

Beyond the pen, the stock trailer sat under its lean-to. Tires clean. A new brass padlock on the hitch.

She hadn’t been waiting for him to come home.

She’d been waiting to stop waiting.

The understanding came slowly, like the ache after a fall—felt only when you put weight on it.

The screen door moved in the wind, breathing without closing.

Inside that house there was nothing to argue with.

No villain. No fight. No last conversation to edit into mercy. Only the consequence of absence, finally collected.

He coiled the rope carefully and hung it back where it belonged. Then he went to the truck and sat behind the wheel.

He didn’t start it.

He rested his forehead against the steering wheel until his breath steadied. Whatever tried to rise in him—grief, apology, a name—never found a clean path out.

When he looked again, the light was going. Porch boards turned the color of old bone. The wind kept moving, indifferent.

He put the key in his pocket.

Not because it meant anything.

Because he didn’t know where else to put it.

The engine caught. The bolt resumed its tapping.

He backed out slowly and pointed the truck toward the road. At the end of the drive he paused once.

The house did not look back.

Then he turned onto the county road and drove until the porch disappeared into mesquite and distance—until it was just another thing the land had taken without comment.