In the autumn of 1902 a young woman rode down from the high ridge country onto the flat Nebraska land. She came alone on a dun mare with a blaze like pale fire across its face. People called the horse restless, but she named it something private and gentle, the way you name a thing you mean to keep close. Her name was Mara Keene. She filed on a quarter-section near the river bend, built a low sod house with her own hands, and set about breaking the ground.

The mare never strayed far. When Mara worked the field the horse grazed nearby; when she rode to town for supplies it followed at an easy trot. Sometimes a small dust devil would rise behind them, spinning for a moment before collapsing back into the earth. She would laugh softly and say the wind was only saying hello.

The first winter arrived without mercy. A hard freeze came in late November and killed the last of the corn standing in the rows. She stood in the doorway watching the stalks blacken, breath clouding the cold air, the mare motionless at her shoulder. She did not weep. She turned back inside and fed the stove until the iron ticked.

Then the big storm rolled in just before Christmas. The sky went the color of old iron, the temperature plunged, and the wind began to howl as though the whole plain had something to say. She went out once to check on the mare—the horse had broken the rope corral and vanished into the blowing white. She called until her throat burned, but the storm ate every sound. She returned to the house shivering, built the fire as high as it would take, and waited.

Three days the blizzard lasted. On the fourth the wind dropped enough for her to step outside. No tracks remained. The mare was gone, the trail north toward the ridge swallowed by drift. She saddled the old work mule, wrapped herself in every quilt she owned, and rode into the white after it.

No one saw her come back.

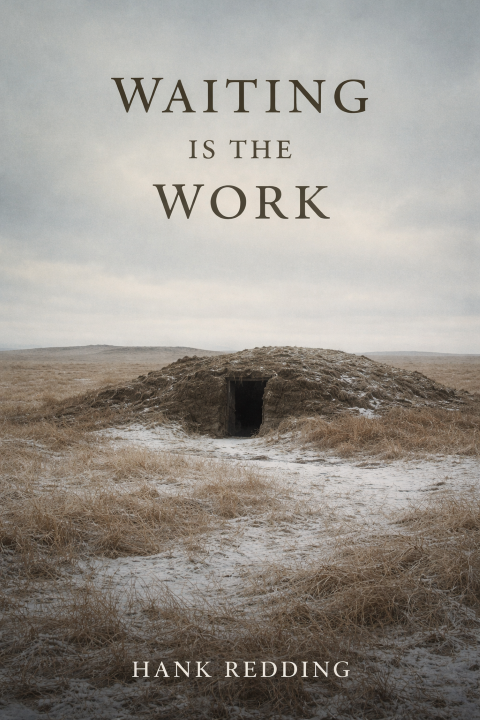

The claim sat empty through the following spring and summer. The sod house slumped, roof caving, door swinging on one hinge. Neighbors took what was useful—the stove, the pump, a few boards—and left the rest to the weather. By the fall of 1903 the walls had melted back into the prairie.

I took the adjoining quarter that October. My name is Caleb Rusk. Thirty-four years old, no wife, no kin left back east worth mentioning. The ground was cheap on account of the talk. I paid no mind to ghost stories. I believed in work and silence, and silence was plentiful here.

One night in early November an owl began to call outside my window. Not once, but six nights straight, the same low, patient hoot after dark. I told myself it was only a bird, but the sound felt aimed, as though it knew I was listening.

On the seventh night I woke to a different stillness. No wind. No owl. Only the kind of quiet that presses against your ears. I lit the lamp and looked out. Moonless, stars thin and far. Then I saw her.

She came down from the high ridge onto the flat land, riding slow and steady. The dun mare moved with its head low, mane lifting in a breeze that did not touch the grass around it. Behind them a small spiral of dust or snow rose and turned, following for a few yards before fading. She wore the same gray coat from the claim papers, hair loose and dark against the night.

She did not turn toward my house. She rode past, eyes fixed on some point ahead, voice low and steady.

The mare never faltered. The spiral thinned to nothing. Then they were gone, swallowed by the dark plain.

I stood at the window until the cold worked through the glass and into my joints. In the morning I walked the line where they had passed. No prints in the frost. No sign at all. Only the same empty land.

I stayed the winter. The owl did not return. The sod house across the way collapsed entirely in a February thaw. I planted wheat the next spring and kept the stove burning late. Sometimes, when the night was still and the moon right, I thought I heard hooves passing far off—slow, unhurried.

I never spoke of it. People carry enough without adding shadows.

But once, in the deep hours, I stepped outside for no reason. The air was sharp. I looked north toward the ridge and said her name aloud, soft as a question.

Nothing answered.

I went back in, closed the door, and slept.

Some things you do not follow. You only wait to see if they will come for you.

And if they do, you ride.